NOTE:

These program notes are published here for patrons of the

Madison Symphony Orchestra and other interested readers. Any

other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author.

Madison Symphony Orchestra

Program Notes

April 11-121-13, 2025

99th Season / Subscription

Program 7

J. Michael Allsen

Guest

conductor Joseph Young leads this program, beginning with

Samuel Barber’s concise Second Essay for

Orchestra. We then welcome the wonderfully eclectic

string trio Time for Three (Tf3). This

genre-bending group, whose performances not only include

string playing and vocals, also embrace a huge range of

musical styles. In

2021, American composer Kevin Puts completed Contact,

kind of “triple concerto” for them. To end, we have

Maestro Young’s selection of movements from one of the

greatest ballet scores of the 20th entry, Prokofiev’s Romeo

and Juliet.

We open with a

great mid-20th-century work, one of the pieces with which

Samuel Barber earned his reputation as one of America’s

leading composers.

We open with a

great mid-20th-century work, one of the pieces with which

Samuel Barber earned his reputation as one of America’s

leading composers.

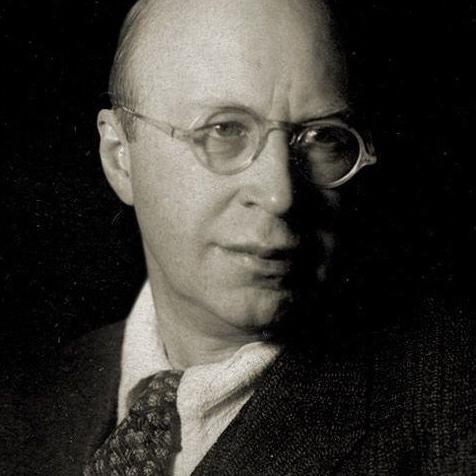

Samuel Barber

Born: March 9, 1910, West Chester,

Pennsylvania.

Died: January 23, 1981, New York City.

Second Essay for Orchestra,

Op.17

• Composed: 1942.

• Premiere: April

16, 1942, with the New York Philharmonic, led by Bruno

Walter.

• Previous MSO Performance: 2017.

• Duration: 11:00.

Background

This work was commissioned by the great

conductor Bruno Walter, who was then leading the New York

Philharmonic.

In the 1940s, Barber was one of a

new generation of American composers— Hanson, Copland,

Diamond, and later Bernstein—whose works were being

programmed with increasing frequency by the world’s great

orchestras. Barber

in particular was championed by several of the period’s

preeminent conductors.

In 1937, Artur Rodzinski conducted Barber’s Symphony No.1 at

the Salzburg Festival—the first American work to be

performed there. The

aging maestro Arturo Toscanini heard the symphony at

Salzburg and asked Barber for a new work, to be played by

the newly-organized NBC Symphony Orchestra. Barber responded

with not one, but two new pieces, the famous Adagio for Strings,

and his [First]

Essay for Orchestra.

Another distinguished conductor who was impressed

by Barber was Bruno Walter, who would eventually record

the Symphony No.1

(the only work

by an American composer recorded by Walter), and who

commissioned him to do a new orchestral work for the New

York Philharmonic. The

result was the Second

Essay.

What You’ll Hear

A

highly concentrated work in which all of the music

material derives from the melody in the opening bars, the

Second Essay

explores a huge range of feelings and textures before

ending in stirring hymn.

The ideal written essay is brief

and economical, treating a single subject. The title Essay allows a

certain freedom of form within a musical work, but the Second Essay fits the

literary definition perfectly. All of its various melodic

ideas are derived from a single theme, spun out at the

beginning by the solo flute.

It also derives a number of distinct moods from

this material—sometime with great vehemence. (A few months

after the premiere, Barber wrote that: “Although it has no program, one

perhaps hears that it was written in war-time.”) The first idea,

quietly introduced by solo woodwinds builds to a gentle

climax in the full strings.

A new theme, melodically similar to the first, is

built up rather quickly to a strident brass passage. A sudden crisp

chord breaks the mood the clarinet begins an intense

fugue—which plays out in several keys at once—that

eventually gives way to an angry scherzo. The Second Essay ends

with a broad hymn, first in the strings, and then even

more dramatically in the brass.

A work composed

during the depths of the Covid lockdown, Contact was

composed in close collaboration—direct and virtual—between

the composer and Time for Three.

A work composed

during the depths of the Covid lockdown, Contact was

composed in close collaboration—direct and virtual—between

the composer and Time for Three.

Kevin Puts

Born: January 3, 1972, St. Louis, Missouri.

Contact

• Composed: 2020-2022.

• Premiere: This work was actually scheduled for a

premiere in June 2020, but this was canceled due to the

pandemic. Tf3 and the Philadelphia Orchestra actually

recorded it, playing to an empty hall, in September 2021.

It was finally premiered live in Tampa Bay by the Florida

Orchestra in March 2022.

• Previous MSO

Performances: This is our first performance of the

work.

• Duration: 30:00

Background

Originally scheduled for a premiere in

December 2020, its performance was delayed by the

lockdown, which, according to Puts allowed, for further

collaboration on the score

Kevin

Puts has had a host of commissions and performances by

leading orchestras, ensembles and soloists throughout

North America, Europe, and the Far East, including the

Pacific Symphony, Utah Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra,

Aspen Music Festival, New York Philharmonic, St. Louis

Symphony, Yo Yo Ma, and many others. Puts won a

Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for his opera Silent Night,

about the famous “Christmas Eve truce” in World War I. His musical

style is intended to be approachable and appealing, and

Puts channels influences as diverse as Copland, Barber,

Adams, Mozart, Beethoven, jazz, and the Icelandic pop

singer Björk—all in his own distinctive musical voice. As he noted in a

2011 interview:

“I know there’s still a fear among some

of us that trying to hold the audience rapt with attention

means you’re selling out, you’re not a real composer. But

for me, composing is much more complicated than the

communication of an abstract idea. First thing, I’ve got

to revel in the kinds of musical language that I care most

deeply about, or I can’t write anything convincing; I

might as well be dead as try to work within someone else’s

aesthetic realm. Second thing—and this is not the primary

aim of every composer, but I admit that it is mine—I want to

communicate. I want audiences to be held in the moment,

and be taken to the next moment. If that’s not happening,

I feel like I’m falling short.”

His openness to an eclectic range of

influences made for a particularly close relationship with

the trio Time for Three.

Puts remembers that:

“In April 2017, I heard the

prodigiously gifted Time for Three perform at Joe’s Pub in

New York City, having recently been contacted about

possibly writing a concerto for them. After hearing them

play, thing, improvise, and perform their own arrangements

and compositions, I felt elated by the infectious energy

they exhibit as a trio. However, I couldn’t imagine

concieving any music they couldn’t improvise themselves!”

Contact is was

initially commissioned for Tf3 by a consortium of

orchestras and by the Sun Valley Music Festival, and was

scheduled for a premiere in June 2020. This plan was

scrapped by the pandemic lockdown, though according to

Puts, the delay allowed for further refinement of the

score, working closely with Tf3—that he:

“collaborated

perhaps more closely than ever before in [my] career to

create music tailored to the group’s unique style of

performance—one which combines dazzling virtuosity,

spontaneity, singing, all manner of string techniques

and an infectious joy for music itself.”

What You’ll Hear

This work is laid out in four movements

• The Call, based

upon a refrain sung by Tf3 at the beginning.

• Codes,

in which terse rhythms support improvisatory-style playing

by the trio,

• The solemn Contact, which moves gradually from tension

towards an uplifting

ending.

• A wild finale, Convivium, based upon a Bulgarian folk

dance.

Puts says that the four movements of

the concerto “tell a story that I hope transcends abstract

musical expression.”

Regarding the first movement, The Call, he asks

“Could the refrain at the beginning of the first movement

be a message from Earth, sent into space?” This haunting

refrain is sung a

cappella by the trio at the beginning and travels

like a passacaglia

theme throughout the orchestra, culminating in a broad

statement by the brass. There is a sudden change in

texture where the trio’s violinists, supported by walking

bass, reinterprets this idea as a new theme, eventually

taken up by the entire orchestra. Horns return to the

original refrain, and the movement ends as it began with a cappella

singing by the trio.

In a similar vein, Puts asks in the

regards to the second movement, Codes, “Could

the Morse-code-like rhythms of the scherzo suggest radio

transmissions, wave signals, etc.?” The movement proceeds

as a set of rhythms barked out by the orchestra,

supporting lively quasi improvisatory playing by the

trio—music that has more than a little resemblance to a

bluegrass hoedown!

Though a science fictional meaning is

implied in the title Contact (as in

the fine 1997 movie of the same name)—the composer

describes an “image of an abandoned vessel, floating inert

in the recesses of space.”—Puts also notes a

meaning related to the pandemic: “The word ‘contact’ has

gained new resonance during these years of isolation and

it is my hope that our concerto will be heard as an

expression of yearning for this fundamental human need.”

The music begins with tense atmospheric textures from the

orchestra, eventually supporting improvisatory music from

the trio. Near the end, there is a shift to a more

positive and uplifting mood.

Convivium implies a happy coming together, and details of

this joyous movement were apparently worked out in

extensive jam sessions between Tf3 and Puts. Here the main

theme is a brisk 11/8 Bulgarian folk dance, Gankino horo. In the second

half of the movement, there are constant reminders of the

“call” motive from the first movement, before the music

ends in a wild conclusion.

Prokofiev’s

Romeo and Juliet,

based upon the Shakespeare tragedy, is among the finest

ballet scores of the 20th century. Here we play a set of

selections from this great work.

Prokofiev’s

Romeo and Juliet,

based upon the Shakespeare tragedy, is among the finest

ballet scores of the 20th century. Here we play a set of

selections from this great work.

Sergei Prokofiev

Born: April 23, 1891, Sontsivka, Ukraine.

Died: March 5, 1953, Moscow, Russia.

Selections from “Romeo and Juliet”

• Composed: 1934-35.

• Premiere: The first concert performance of the

full score took place in Moscow in October of 1935. The ballet was

not staged until 1938, with a production in Brno,

Czechoslovakia, and it was finally performed in Russia in

1940, with a production by the Kirov Ballet of Leningrad

(St. Petersburg).

• Previous MSO

Performances: We have played excerpts from the score

at these concerts in 1954, 1984, 1999, 2009, and 2018.

• Duration: See

note below.

Background

This work’s premiere in Prokofiev’s

native Russia was delayed for several years by musical

politics.

There is little doubt these days that Romeo and Juliet

stands as Prokofiev’s most enduring ballet score. For

several years, however, this enormous work was a victim of

Soviet artistic politics.

The original idea for this full-scale Romantic

ballet on Romeo and

Juliet seems to have come from Sergei Radlov, an

influential Leningrad opera director who had collaborated

on Prokofiev’s opera The Love for Three

Oranges. The “story-ballet” Romeo and Juliet

was to have been produced at Leningrad’s Academic Theater,

but at the end of 1934 the theater underwent a sudden

change of administration.

Sergei Kirov, the Party boss of Leningrad, was

assassinated, undoubtedly at Stalin’s order, and in an

incongruous move, the Soviet authorities renamed the

Academic Theater to honor this “Socialist martyr.” The new Kirov

Theater was tightly controlled by the Soviet artistic

bureaucracy, and Radlov—whose views had long been

considered suspiciously avant garde—fell out of favor with the

authorities. Hopes for producing Romeo and Juliet

in Leningrad evaporated, and Prokofiev began working with

the Bolshoi ballet in Moscow. The score was

completed in 1935 and played at the Bolshoi, whose

directors pronounced the music “undanceable” and canceled

the planned production.

At least part of the problem was the story line,

which had been twisted at Radlov’s suggestion, so that a

suicidal Romeo arrived at Juliet’s tomb just a minute after she woke

up, thus providing the most famous of all tragedies with a

happy ending!

Despite these disappointments,

Prokofiev continued to work on the ballet, fixing the

sappy ending, and extracting two orchestral suites from

the score. The

concert suites he extracted from the ballet were

enormously popular, both inside the Soviet Union and in

Europe and the United States. In late 1938, the Kirov

Ballet finally agreed to produce Romeo and Juliet. Their change of

heart seems to have been inspired in part by the success

of the suites, but also by some embarrassment over the

fact that a non-Soviet company (in Czechoslovakia) had

actually staged the ballet in 1938. The Kirov’s

lavish production in 1940 was a huge success, and the

ballet finally found a secure place in the Russian

repertoire—the critics hailed Romeo and Juliet

as a triumph of Soviet art, and hailed Prokofiev the

ballet composer as the first worthy successor to

Tchaikovsky.

What You’ll Hear

Prokofiev’s evocative music is the

perfect counterpoint to Shakespeare’s tragedy.

Movements from the ballet are often

mixed and matched, as at this concert [NOTE: AS of when I posted these notes

online in June 2024, we did not yet know which sections

of the ballet score Mr. Young would be programming. I

will complete these notes when we have that repertoire.

Please check back later in the season. -JMA]

________

program notes ©2024 by J. Michael

Allsen