NOTE: These program notes are published here for

patrons of the Madison Symphony Orchestra and other interested

readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific

permission from the author.

Madison

Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

November

15-16-17, 2024

99th

Season / Subscription Program 3

J.

Michael Allsen

Guest

conductor Michael Stern opens the program with Johnathan

Leshnoff’s intense Rush

for Orchestra. This is a driving and exciting work

that builds up a

tremendous amount of momentum throughout. We then welcome

back pianist Garrick

Ohlsson: a favorite of the audience and the orchestra—for

his sixth performance

with the MSO. In previous visits, he has played

Rachmaninoff’s Piano

Concerto No. 3 (1984 and 2008), Mozart’s

Piano Concerto No.25 (1985) Brahms’s Piano

Concerto No. 2 (2002) and Tchaikovsky’s seldom-heard

Piano Concerto No. 2 (2012); Here he plays

a familiar favorite,

Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto, a romantic

masterpiece infused with the

spirit of Grieg’s Norwegian homeland. We end with the

powerful fifth symphony of

Dmitri Shostakovich. This sometimes bombastic work, which

Shostakovich humbly

described as “the practical answer of a Soviet artist to

justified criticism,”

in fact seems to be have been a subtle and bitter reaction

to the Soviet Union of

Joseph Stalin.

Maestro

Stern conducted the premiere of this work in 2009.

Maestro

Stern conducted the premiere of this work in 2009.

Jonathan Leshnoff

Born: September 8,

1973, New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Rush

•

Composed: 2008.

•

Premiere: January

31, 2009, in Germantown

Tennessee, by the IRIS Orchestra, under the direction of

Michael Stern.

•

Previous MSO

Performances: This is our

first performance of the work.

•

Duration: 8:00.

Background

Jonathan

Leshnoff is among the most important and

frequently-programmed of American

contemporary composers.

GRAMMY-nominated

Jonathan Leshnoff has been described by the The New

York Times as “a

leader of contemporary American lyricism.” His music runs

the gamut from small

orchestral works like Rush through

symphonies

(four, to date) and over a dozen concertos, to six

full-size oratorios, to

chamber and wind band music. Lehnoff has written these

works for some of the

world’s leading soloists—Joyce Yang, Gil Shaham, Roberto

Díaz and others—and

for America’s leading orchestras: Philadelphia Orchestra

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra,

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Dallas Symphony Orchestra,

Kansas City Symphony,

Nashville Symphony Orchestra, and the Pittsburgh Symphony

Orchestra. He is

currently on the faculty of Towson University in

Baltimore. Rush

is one of several works written by

Leshnoff for Maestro Stern and the IRIS Chamber Orchestra.

What You’ll Hear

A

short, intense work, Rush alternates

between the fierce mood of the opening, and calmer music

for solo clarinet and

harp.

Rush, scored for a

chamber orchestra, is an exercise in the concentrated

development of a single

motive, heard at the outset. Its furious forward motion is

broken in the middle

of the work by a lyrical clarinet solo. The ferocious mood

of the opening

gradually returns, only to be halted once more near the

end of the work by the

clarinet and a lovely solo cadenza by the harp. At the

very end, the fury returns

in a brief coda.

This

is Grieg’s only concerto and one of his relatively few

large orchestral pieces,

but it has become one of the most important romantic

concertos for piano.

This

is Grieg’s only concerto and one of his relatively few

large orchestral pieces,

but it has become one of the most important romantic

concertos for piano.

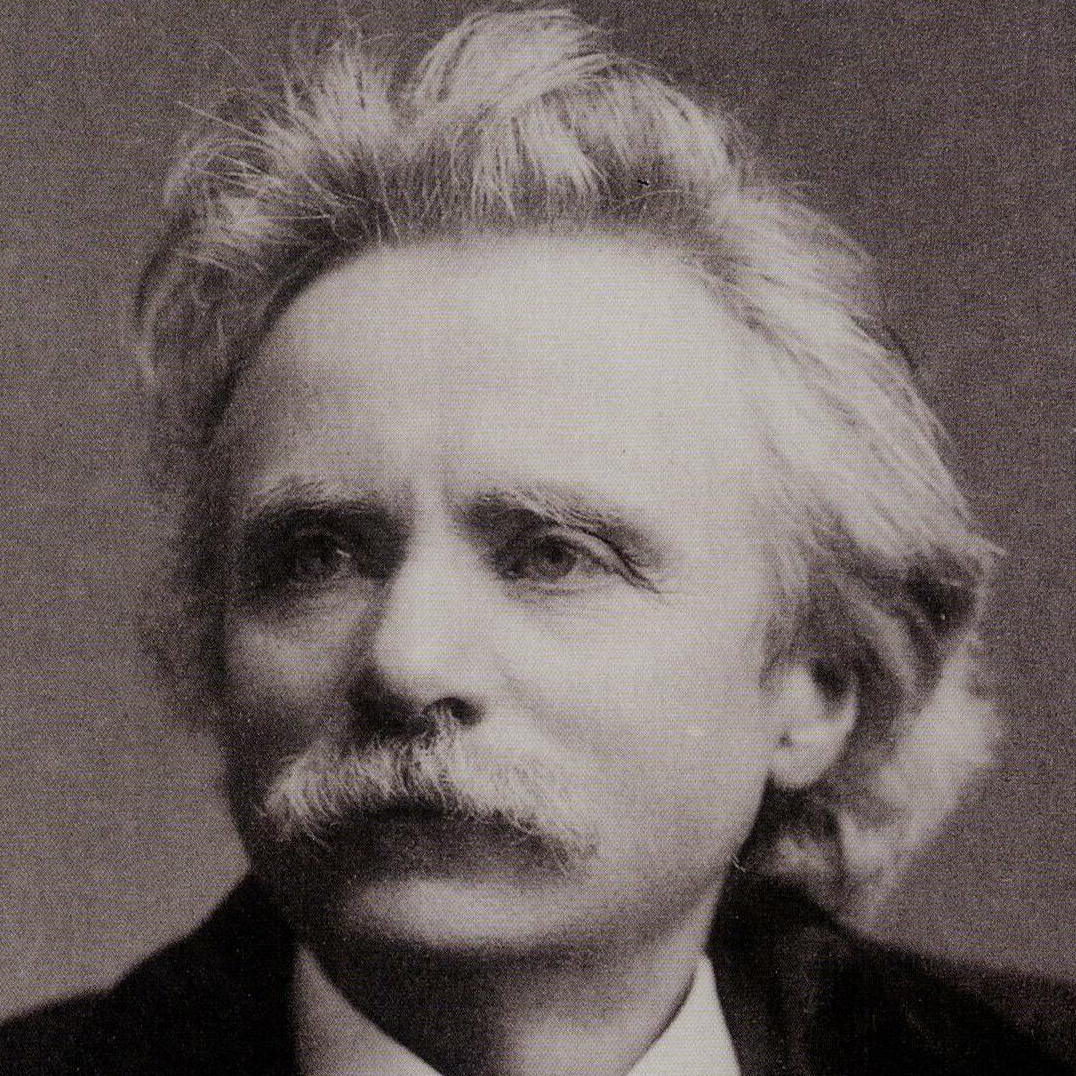

Edvard Grieg

Born: June 15, 1843,

Bergen, Norway.

Died: September 4,

1907, Bergen, Norway.

Piano Concerto in

A minor, Op. 16

•

Composed: 1868.

•

Premiere: April 3,

1869, in Copenhagen, with Edmund Neupert as

soloist

•

Previous MSO

Performances: Previous

performances at these concerts have featured Elsa Chandler

(1927), Storm Bull

(1929), Audun Ravnan (1971), Howard Karp (1984), Santiago

Rodriguez (1993), Jasminka

Stancul (2005), and André Watts (2011).

•

Duration: 32:00.

Background

The

Piano Concerto,

written when he was

just 25 years old, was a career-making piece for Grieg,

among his first pieces

to attract notice and performances outside of his native

Norway.

In

an age of musical nationalism, Norwegian Edvard Grieg

firmly identified himself

with the music of his homeland. Grieg's works are often

built using German

Classical forms, but his melodies, which are at once

lyrical and folk-like, are

firmly rooted in the Norwegian musical traditions he knew

and loved. In

describing his approach to composition, Grieg once wrote:

“Composers with the

stature of a Bach or Beethoven have erected grand churches

and temples. I have

always wished to build villages: places where people can

feel happy and

comfortable ...the music of my own country has been my

model.”

Grieg's

piano concerto was written during the summer of 1868, when

he and his family

were on holiday in Sölleröd, near Copenhagen. While it is

dedicated to the

pianist Edmund Neupert, there are also close connections

between Grieg and the

preeminent piano virtuoso of the 19th century, Franz

Liszt. By 1868, when he

first saw some of Grieg's music, the 57-year-old Liszt had

taken minor Catholic

orders (although he was never ordained as a priest), and

was dividing his time

between the court at Weimar and a Roman monastery. Liszt

wrote a very

complimentary letter to Grieg, inviting him to come for a

visit. Grieg brought

this letter to the attention of a Norwegian government

ministry, which granted

him funds to travel to Rome in October of 1869.

Understandably, Grieg brought

the manuscript of his concerto along. According to Grieg's

account of the

meeting, Liszt asked him to play through the concerto, and

when Grieg declined

(he had not practiced it): “...Liszt took up the

manuscript, went to the piano,

and said to the assembled guests with a smile, ‘Very well,

then, I will show

you that I also cannot.’” Grieg goes on to tell how Liszt

sight-read the

concerto with great verve, ending with words of

encouragement: “Keep steadily

on your course. I tell you, you have the stuff in

you—don't let them intimidate

you!” When the concerto was published, it was dedicated to

the late composer

Rikard Nordraak, who wrote the melody to Ja, vi elsker dette

landet, which would

become the Norwegian national anthem.

What You’ll Hear

A

fervent Norwegian musical nationalist, Grieg tried to

infuse the style of

Norwegian folk music into nearly all of his works. The

concerto is in three

movements:

• A broad opening

movement in sonata form.

• A set of Adagio variations.

• A fast-paced finale based upon a series of

folklike themes.

The

Piano Concerto

has been a regular

part of the romantic concerto repertoire since the late

19th century. It is set

in three movements, following the strictest German models

in matters of form,

but Grieg's Norwegian heritage shows through in every

passage, in his regular

phrasing and in his lyrical melodies. The stormy

introductory flourish in the

piano that opens the first movement (Allegro

molto moderato) leads into a marchlike theme

introduced by the woodwinds

and restated by the piano. Cellos and trombones introduce

the more passionate

second theme. Grieg's fiery cadenza at the end of the

recapitulation serves to

further develop the opening march theme. Grieg rounds off

the movement with a

brief coda—a new theme spun off from the march, and a

return to the opening flourish.

The

serene Adagio

is a series of free

variations on a calm, hymnlike theme introduced by muted

strings. Orchestra and

soloist first develop this theme in the manner of a

dialogue, but eventually

combine their lines in the final statement. The closing

measures of the Adagio

lead directly into the third

movement (Allegro

moderato molto e

marcato). This closing movement is set as a rondo,

in which Grieg uses five

different themes, all of them having a distinctly folklike

character. The movement

comes to its climax with a brief but intense cadenza that

develops the fifth of

these themes.

Shostakovich’s

fifth

symphony, composed in the deeply repressive atmosphere of

Joseph Stalin’s

Soviet Union, is a symbol of resistance and humanity in

the face of totalitarian

opression.

Shostakovich’s

fifth

symphony, composed in the deeply repressive atmosphere of

Joseph Stalin’s

Soviet Union, is a symbol of resistance and humanity in

the face of totalitarian

opression.

Dmitri

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Born: September 25,

1906, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Died: August 9, 1975,

Moscow, Russia.

Symphony No. 5,

Op. 47

•

Composed: 1937.

•

Premiere: in

November 21, 1937 in Leningrad (St.

Petersburg), by the Leningrad Philharmonic, under the

direction of Yevgeny Mravinsky.

•

Previous MSO

Performances: It has been

played three times previously at our concerts, in 1980,

1993, and 2006.

•

Duration: 44:00.

Background

Shostakovich,

who was in deep trouble with the authorities in 1937,

meekly described his

fifth Symphony as a “practical answer of a Soviet artist

to justified criticism.”

However, he seems to have put one over on Soviet

authorities!

Music

and the arts are potent symbols of humanity and freedom,

and totalitarian states

invariably seek to control them for their own purposes. In

Josef Stalin's

Soviet Union, state supervision of the arts was a powerful

and controlling

reality. A manifesto outlining the principles of

“Socialist Realism” appeared

in 1933. This doctrine was originally intended to control

the content and style

of Soviet literature, but it was quickly adapted to the

visual arts, film, and

music. As explained in an article published by the Union

of Soviet Composers:

“The main

attention of the Soviet composer

must be directed towards the victorious progressive

principles of reality,

towards all that is heroic, bright, and beautiful. This

distinguishes the

spiritual world of Soviet man, and must be embodied in

musical images full of

beauty and strength. Socialist Realism demands an

implacable struggle against

those folk-negating modernistic directions typical of

contemporary bourgeois

art, and against subservience and servility towards modern

bourgeoisie culture.”

In

practice, Soviet music of this period served the

propaganda needs of the state,

and was aimed at proletarian consumption. Composers

abandoned “formalist”

devices—unrestricted dissonance, twelve-tone technique,

etc.—in favor of

strictly tonal harmonies and folk music (The designation

“formalist” was eventually

used to describe just about anything an official critic

didn’t like.).

Shostakovich

struggled heroically within this system. There was a

continuing pattern in his

works of the 1930s and 1940s of perilously pushing the

limits of official

tolerance and then rehabilitating himself with a work that

seemed to conform

more closely to the Party line. In 1934, his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was a rousing

success, and continued to run

for over 100 performances. In 1936, however, Stalin

himself attended a

performance, and left the theater in a rage. Within a few

days, a review of the

opera appeared in Pravda,

complaining

of an “intentionally dissonant, muddled flow of sounds,”

and angrily denouncing

its anti-Socialist “distortion.” Shostakovich was quickly

transformed from one of

the young lions of Soviet music to a suspected Formalist,

and articles

published in Pravda

and the bulletin

of the Composers' Union began to reveal “modernistic” and

“decadent” elements

in many of his works that had previously been blessed by

Soviet authorities. The

composer immediately cancelled the premiere of his fourth

symphony, fearing

that the dissonant nature of this score would push the

authorities too far. He

was so certain, in fact, that Stalin's goons would appear

at his door that he

kept a small suitcase in his apartment, packed for his

trip to the Gulag

Archipelago. A hastily-composed ballet glorifying life on

a collective farm was

not enough put him back in favor with the Composers'

Union, but with the

performance of his Symphony

No.5 in

November of 1937, Shostakovich regained a certain amount

of his position in the

hierarchy of Soviet musicians.

The

usual story of the symphony’s composition is that it was

written very quickly,

between April and July 1937. But in a note to his

recently-published critical

edition of the score, Manashir Iakubov shows that in fact

it was a much more

extensive process lasting from April up through just a few

weeks before the

November premiere. On its surface, the Symphony

No.5 seems to be a meek acquiescence—in fact

Shostakovich humbly subtitled

the work “The practical answer of a Soviet artist to

justified criticism,” and

it was composed in honor of the 20th anniversary of the

1917 revolution. In

describing the fifth symphony at its premiere,

Shostakovich wrote: “The theme

of my symphony is the making of a man. I saw humankind,

with all of its

experiences at the center of this composition, which is

lyrical in mood from

start to finish. The Finale is the optimistic solution of

the tragedy and

tension of the first movement. …I think that Soviet

tragedy has every right to

exist. However, the contents must be suffused with

positive inspiration… ” All

safely Socialist sentiments—but hearing the Symphony

No.5, I am struck not so much by the triumph and

optimism of the Finale,

but by the deeply personal anxiety and sense of suffering

that underlies the

entire work.

The

premiere was a phenomenal success and Soviet officials

were quick to

investigate what all the fuss was about. The Committee on

Art Affairs dispatched

two of its members to Leningrad to hear a later

performance, they explained

that tempestuous applause at the end was because the

promoters had hand-picked

the audience, excluding “ordinary, normal people.” But a

subsequent performance

for hand-picked Party officials and guests was just as

successful. Official

suspicion persisted— one musical official cited the

“unwholesome stir around

this symphony”—but in this case, Soviet authorities seem

to have decided to put

a positive spin on the affair and accept the popularity of

this work at face

value. Glowing reviews followed in the official press. The

review by composer

Dmitri Kabalevsky was typical: “After hearing

Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, I

can boldly assert that the composer, as truly great Soviet

artist, has overcome

his mistakes and taken a new path.”

The

audiences at these early performances were probably more

perceptive, however. Many

members of the audience wept at the premiere, and the

applause following the

performance lasted nearly half an hour—facts that were

reported in the official

press as an emotional response to the symphony's uplifting

conclusion. As

Shostakovich wrote some 25 years later (well after Stalin

was safely dead and

repudiated): “Someone who was incapable of understanding

could never feel the

Fifth Symphony. Of course they understood—they understood

what was happening

around them and they understood what the Fifth was about.”

This work was indeed

a “response to criticism,” but it was a much more tragic

and anguished response

than the authorities chose to believe.

What You’ll Hear

The

symphony is in four movements:

•

A tragic and menacing opening.

•

A humorous scherzo.

•

A luminous third movement for solo woodwinds

and strings.

•

A bombastic finale, that closes in a triumphant

mood.

The

tragic character of this symphony is established in the

opening bars (Moderato),

in an angular, off-beat

melody introduced by the low strings. Much of the

beginning is devoted to an

imitative exposition of this melody in the strings. A

rhythm appears in the

lower strings, repeating incessantly beneath the second

main theme, a lyrical

melody in the first violins. This melody is built over the

same large leaps as

the opening theme, but here the effect is more melancholy

than tragic. After

flute and clarinet solos comment upon this theme, the

horns introduce a more

menacing march-like melody. This march increases in

intensity until the

climactic return of the opening theme. Near the close of

the movement the

second theme returns, now on a more hopeful note, in the

solo flute.

For

the main theme of the scherzo (Allegretto),

Shostakovich parodies a melody from his Symphony

No.4. The irony is obvious—here was a work that was

unknown to the

audience, and that, the composer felt, would never be

performed. So the outward

humor of this movement—bumptious bass lines, woodwind

trills and

tongue-in-cheek violin solos—overlays a bitterly sarcastic

comment on Socialist

Realism. A military-sounding waltz alternates with this

main theme in the

manner of a trio. At the end, he uses one of Beethoven's

favorite jokes: what

seems to be yet another repeat of the trio, played

hesitantly by a solo oboe,

is brusquely tossed aside by the brass, and the movement

ends abruptly

The

third movement (Largo)

belongs

entirely to the strings and solo woodwinds. Shostakovich

divides the string

section into eight parts throughout this movement, weaving

complex counterpoint

around a single somber melody. Flutes and harp introduce a

second subject which

is gradually woven together with the first. In a very

beautiful central

passage, solo woodwinds expand on the main themes above an

effectively simple

background of string tremolos. The movement builds

gradually towards its

climax, a return of the first theme in the full string

choir, before fading

away at the end. Though it is overshadowed by the broad

opening movement and

the powerful finale, the Largo may

have been the movement that had the deepest impact at the

premiere. Much of the

weeping in the audience took place during the Largo, leading biographer David Fanning to

suggest that the

movement was “...a channel for a mass grieving at the

height of the Great

Terror, impossible otherwise to express openly.”

The

finale (Allegro non

troppo) is set as

a rondo, and brings the symphony to a properly jubilant

finish. The main theme

is an almost violent march, which alternates with several

quieter sections. Shostakovich

brings back reminiscences of several moments from

preceding movements, building

towards a massive coda in D Major. The composer's own

program note (and the

official reviewers) described the finale as triumphant and

exultant. Once

again, Shostakovich's intent in this movement may well

have been sarcasm,

rather than exaltation.

________

program

notes ©2024 by J. Michael

Allsen