NOTE: These program notes are published here for

patrons of the Madison Symphony Orchestra and other interested

readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific

permission from the author.

October 18-19-20, 2024

99th Season / Subscription

Program 2

J. Michael Allsen

Visions

lie at the heart of the works heard on this program,

which is led by guest

composer conductor Nicholas Hersh. British

composer Anna Clyne, whose music is making its first

appearance at a MSO

program, based her work This Midnight Hour upon

poetic visions by

Charles Baudelaire and Juan Ramón Jiménez. Violinist

Kelly Hall-Tompkins played a

stunning performance of the Wynton Marsalis Violin

Concerto in 2022. She

returns here to perform two works, beginning with the

gentle The Lark

Ascending by Ralph Vaughan Williams, based upon a

poem by George Meredith.

She then plays plays Tzigane, Maurice Ravel’s

virtuosic take on Roma

fiddling, written for the Hungarian violinist Jelly

d’Arani. And

to end the program we play the monumental

Symphonie fantastique by Hector Berlioz, a

passionate and often

disturbing musical vision ending with a trip to hell!

Leading

British composer Anna Clyne, who now resides in New

York, wrote this exciting

work for L’Orchestre national d’Île-de-France in Paris.

Leading

British composer Anna Clyne, who now resides in New

York, wrote this exciting

work for L’Orchestre national d’Île-de-France in Paris.

Anna Clyne

Born: March 9, 1980,

London, United Kingdom.

This

Midnight Hour

- Composed: 2015.

- Premiere: November 13, 2015, in

Paris, by the

Orchestre national d'Île de France, Enrique Mazzola.

director.

-

Previous MSO Performances: This is our

first performance of the work.

-

Duration: 12:00.

Background

Clyne

frequently sees her works as collaborations, and many of

her orchestral works,

including this one, have arisen out of her

collaborations with the orchestras for

which she has been a composer-in-residence.

Among the leading

British composers of her generation, Anna Clyne was born

in London and was

composing by age 11. She studied at the University of

Edinburgh and the

Manhattan School of Music. Clyne has served as

composer-in-residence with the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Baltimore Symphony

Orchestra, L’Orchestre

national d’Île-de-France in Paris, anD the Scottish

Chamber Orchestra. in

2024, she has just completed residencies with orchestras

in Finland, England,

and Spain. Clyne’s

inventive music spans

a wide range of styles, from electroacoustic works to

more traditional works

for orchestra, chamber ensembles, and chorus. This Midnight Hour was composed during her

residency in Paris

What You’ll Hear

This

evocative score draws upon images from poems by Jimenez

(of mad energy) and

Baudelaire (of a “melancholic waltz”).

Clyne

provides the following description of the piece:

“The

opening to This Midnight Hour is inspired

by the character and power of the lower strings of

L'Orchestre national d'Île

de France. From here, it draws inspiration from two

poems—one by Charles

Baudelaire and another by Juan Ramón Jiménez. Whilst it

is not intended to

depict a specific narrative, my intention is that it

will evoke a visual

journey for the listener. Jiménez’s La

musica is very

short

and concise:

“Music—

a naked woman

running mad through the pure night

(translated

by Robert Bly)

“This

immediately struck me as a strong image and one

that I chose to interpret with outbursts of frenetic

energy, for example,

dividing the strings into sub-groups that play fortissimo staggered descending cascade

figures from left to right

in stereo effect. This stems from my early explorations

of electroacoustic

music. There is also a lot of evocative sensory imagery

in Baudelaire’s Harmonie

du Soir, the first stanza of which reads as

follows:

“The season is at

hand when swaying on its stem

Every

flower exhales perfume like a

censer;

Sounds

and perfumes turn in the

evening air;

Melancholy

waltz and languid vertigo!

(translated

by William Aggeler)

“I

riffed on the idea of the melancholic waltz about

halfway into This Midnight Hour—I split the

viola section in two and

have one half playing at written pitch and the other

half playing 1/4 tone

sharp to emulate the sonority of an accordion playing a

Parisian-esque waltz.”

The piece starts

with hectic “running” music, with a forceful line from

the low strings and

jagged bursts from the woodwinds. Clarinets and

introduce a languid new idea

before a static interlude punctuated by the drums.

Another frantic episode

leads into Clyne’s rather woozy “melancholic waltz.” The

piece ends with a

calm, folklike idea, overlaid with a sometimes bluesy

solo trumpet.

This

tranquil work was written directly after Vaughan

Williams returned home from the horrors of World War I.

This

tranquil work was written directly after Vaughan

Williams returned home from the horrors of World War I.

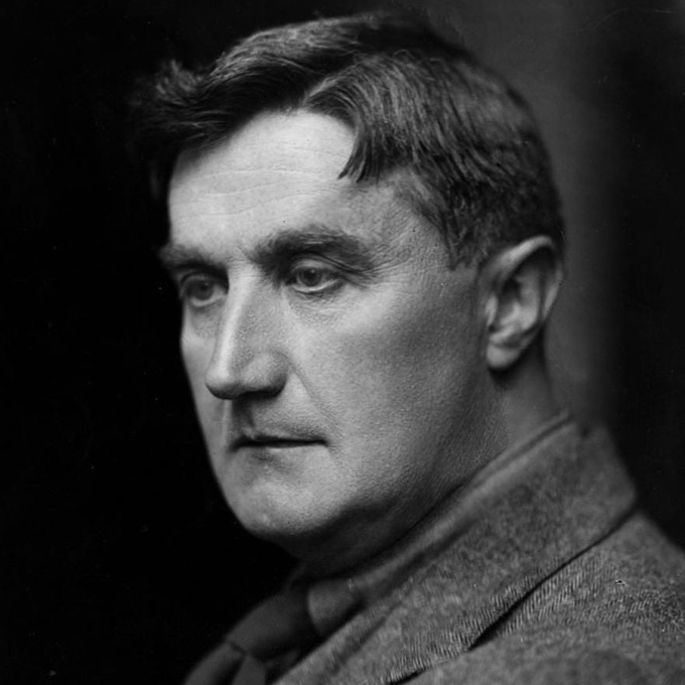

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Born: October 12, 1872, Down Ampney,

United Kingdom.

Died: August 26, 1958, London,

United Kingdom.

The Lark

Ascending

- Composed: Completed

in

1920.

- Premiere: Marie

Hall, to whom the score is dedicated, played The Lark Ascending at its first

performance, with piano

accompaniment, in December,

1920. Six

months later the composer’s friend Adrian

Boult conducted her in the premiere of the

orchestral version in London.

- Previous MSO Performances: We have

performed the work once previously, in 1978, with MSO

concertmaster Norman

Paulu as soloist.

- Duration: 13:00.

Background

Marie Hall, dedicatee of the

score, was a leading

British violinist of the day, and one of the first

female violinists to have a

truly international career.

Though he was nearly

42 at

the outbreak of World War I, Vaughan Williams

volunteered for service almost

immediately, setting composition aside for the duration

of the war. He served

first as an ambulance orderly and then as an artillery

officer, and at the end

of the war, he was named Music Director of the First

Army in France. Returning

to England, he took up a position

as Professor of Composition at the Royal College of

Music, and began composing

again with great intensity. Among the

works he had sketched out before the war was The Lark Ascending, and he revised the

score extensively in

1920. Vaughan

Williams dedicated it to

Marie Hall, one of the most eminent violin soloists of

the early 20th century.

Hall advised him on the solo part. One of the

reviewers said that it “showed serene disregard for

the fashions of today or

yesterday.” The Lark Ascending

is based upon a short poem by

the popular Victorian

writer George Meredith, which Vaughan Williams

includes in the score:

He rises and begins to round,

He drops the silver chain of sound,

Of many links without a break,

In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake.

For singing till his heaven fills,

‘Tis love of earth that he instils,

And ever winging up and up,

Our valley is his golden cup

And he the wine which overflows

To lift us with him as he goes.

Till lost on his aerial rings

In light, and then the fancy sings.

What You’ll Hear

The solo violin

winds

out a lovely melodic line above a lightly-scored

orchestral accompaniment.

The work is an

exercise in serenity. The orchestra

begins with a hushed, expectant passage before the solo

line enters, ascending

to the violin’s upper range in a series of short phrases

reminiscent of

birdsong. This

outwardly simple melody

uses just a few pitches: one of my teachers jokingly

referred to this piece as

“Vaughan Williams’s loving tribute to the pentatonic

scale.” But it is

thoroughly lovely, played above the simplest

accompaniment. There

is a change of character, to a lyrical

theme played by the orchestra, as the solo part

“chirrups” a lively

decoration. Vaughan

Williams introduces

a new idea, a stolid folk dance that leads to an avian

cadenza. The

orchestra introduces a third theme, a

broad folklike melody.

The piece closes

with a final reprise of the opening music, and a solo

violin passage that fades

to nothingness as the lark vanishes in the misty

heights.

The work is an

exercise in serenity. The orchestra

begins with a hushed, expectant passage before the solo

line enters, ascending

to the violin’s upper range in a series of short phrases

reminiscent of

birdsong. This

outwardly simple melody

uses just a few pitches: one of my teachers jokingly

referred to this piece as

“Vaughan Williams’s loving tribute to the pentatonic

scale.” But it is

thoroughly lovely, played above the simplest

accompaniment. There

is a change of character, to a lyrical

theme played by the orchestra, as the solo part

“chirrups” a lively

decoration. Vaughan

Williams introduces

a new idea, a stolid folk dance that leads to an avian

cadenza. The

orchestra introduces a third theme, a

broad folklike melody.

The piece closes

with a final reprise of the opening music, and a solo

violin passage that fades

to nothingness as the lark vanishes in the misty

heights.

Hungarian music,

particularly that

of the Roma people, has been fascinating composers from

the time of Mozart

onwards. This work by Ravel attempts to capture the

excitement of Roma

fiddling.

Hungarian music,

particularly that

of the Roma people, has been fascinating composers from

the time of Mozart

onwards. This work by Ravel attempts to capture the

excitement of Roma

fiddling.

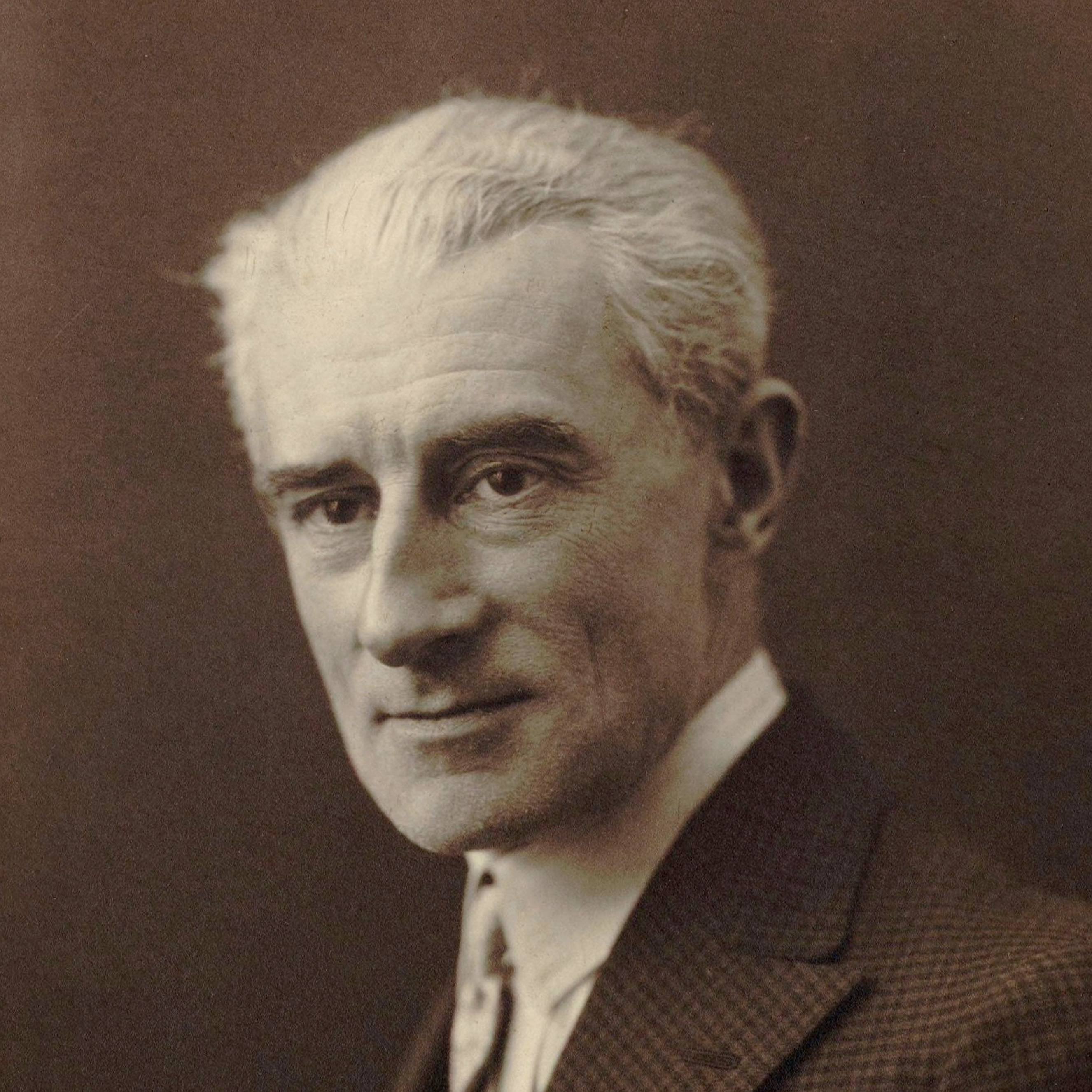

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, Ciboure, France.

Died: December

28, 1937, Paris, France.

Tzigane

- Composed: 1922-24.

- Premiere: A version

for violin and piano was premiered in London by Jelly

d’Arani, violin, and

Henri Gil-Marchex, piano, on April 26, 1924. Ravel

completed the orchestral

version a few months later, and this version was

premiered in Paris on November

30, 1924, with d’Arani as soloist.

- Previous MSO Performances: Previous MSO

performances have featured Vartan Manoogian (1982) and

Laura Frautschi (1997).

-

Duration: 10:00.

Background

Jelly d’Arani, the Hungarian

violinist who inspired Ravel to compose this work, had

settled in London by 1922,

after years of successful tours. She was an excellent

player, but also did not

shy away from using her “exotic” Roma heritage to

further her career.

During the early 1920s,

Maurice Ravel was in a severe compositional slump. His

spirit and Parisian

musical society had been devastated by World War I, and

he was deeply depressed

over the death of his mother. He managed to complete his

Violin Sonata in 1922, but the years

leading up to this were

extremely unproductive. In July of 1922, Ravel was

invited to a private concert

where the Hungarian violinist Jelly d’Arani played the

recently-completed

sonata. Ravel was entranced by her playing, and was

particularly fascinated by

her Hungarian musical heritage. He asked her to play

some authentic Roma tunes,

and eventually the two stayed together until 5:00 in the

morning, discussing

Hungarian music. Tzigane

(meaning

“Gypsy”) was obviously inspired by this experience, and

although it was

relatively slow in coming, it marked the beginning of a

new period of

creativity for Ravel.

During the early 1920s,

Maurice Ravel was in a severe compositional slump. His

spirit and Parisian

musical society had been devastated by World War I, and

he was deeply depressed

over the death of his mother. He managed to complete his

Violin Sonata in 1922, but the years

leading up to this were

extremely unproductive. In July of 1922, Ravel was

invited to a private concert

where the Hungarian violinist Jelly d’Arani played the

recently-completed

sonata. Ravel was entranced by her playing, and was

particularly fascinated by

her Hungarian musical heritage. He asked her to play

some authentic Roma tunes,

and eventually the two stayed together until 5:00 in the

morning, discussing

Hungarian music. Tzigane

(meaning

“Gypsy”) was obviously inspired by this experience, and

although it was

relatively slow in coming, it marked the beginning of a

new period of

creativity for Ravel.

What You’ll Hear

Though they were closely

contemporary

pieces, Ravel takes an approach in Tzigane

that is entirely different from that of

Vaughan-Williams: here the focus is

entirely on the violin part, which is filled to the brim

with astonishing

technical feats.

Ravel’s friend,

violinist

André Polah, who advised him on technical details of the

solo part, wrote that:

“Ravel’s idea was to represent a [Roma violinist]

serenading a beautiful

woman—real or imaginary—with his fiery temperament and

with all the resources

of good and bad taste at his command. In the solo part,

Ravel has not only uses

every known technical effect, but has invented some new

ones!” Ravel was

particularly adept at absorbing musical influences, and

in Tzigane he creates his own version of

Hungarian music. The work

opens with a lengthy and spectacular solo cadenza that

manages to capture the

essence of Roma fiddling, together with echoes of the

19th-century violin

virtuoso Niccoló Paganini. When the orchestra finally

enters, it provides a

rich, but inobtrusive background to an

ever-more-complicated battery of

virtuoso techniques: rapid harmonics, quadruple stops,

and an amazing passage

that calls upon the player to play pizzicatti

with the left hand in the midst of bowed arpeggios.

Okay, I’m just

going to say it:

Hector Berlioz was one strange dude...

Okay, I’m just

going to say it:

Hector Berlioz was one strange dude...

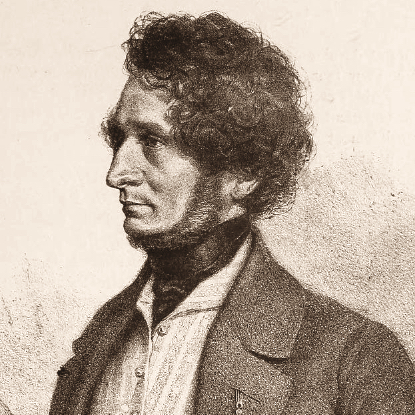

Hector Berlioz

Born: December

11, 1803, La

Côte-Saint-André,

France.

Died: March

8, 1869, Paris, France.

Symphonie

fantastique (Fantastic

Symphony), Op. 14

- Composed: Berlioz’s

Symphonie

fantastique, which he

subtitled “Episode in the Life of an Artist,” was

written between 1829 and

1830.

- Premiere: December

5, 1830 at the Paris Conservatoire, under the

direction of François-Antoine

Habaneck.

- Previous MSO Performances: Previous performances by the

Madison Symphony

Orchestra were in 1973, 1983, 1997, 2006 and 2015.

-

Duration: 55:00.

Background

This grand, programmatic work

was

inspired by Berlioz’s obsessive love for English actress

Harriet Smithson.

If we were to paint

a picture

of the archetypical Romantic Composer, we could probably

use Hector Berlioz as

a model. Six

feet tall, with a huge mop

of hair and a passionate personality, Berlioz was nearly

always in a state of

emotional upheaval—upheaval reflected in his copious

writings and

larger-than-life compositions. All of his compositions

illustrated his

passions, but none is more directly (and disturbingly)

autobiographical than

his Symphonie

Fantastique.

The story behind this work reads like a

Hollywood screenplay...

Scene

1: Paris,

1827.

Berlioz (a young Gérard Depardieu? Johnny Depp in

a red wig?), a

passionate young composer, sees Shakespeare’s Hamlet for the first time.

He is in ecstasy over the play, despite the fact

that the performance

was in English, a language he does not understand. What really

makes an impression on him, however, is Harriet

Smithson, the English actress

in the role of Ophelia (if contemporary descriptions of

her are accurate, Lena

Dunham would be perfect.) Berlioz is immediately

obsessed with Smithson, and

writes to her with a marriage proposal—the first of

dozens of love letters. Rather

than taking out a restraining order, she simply leaves

Paris in 1829 without

ever acknowledging Berlioz’s existence.

Scene

1: Paris,

1827.

Berlioz (a young Gérard Depardieu? Johnny Depp in

a red wig?), a

passionate young composer, sees Shakespeare’s Hamlet for the first time.

He is in ecstasy over the play, despite the fact

that the performance

was in English, a language he does not understand. What really

makes an impression on him, however, is Harriet

Smithson, the English actress

in the role of Ophelia (if contemporary descriptions of

her are accurate, Lena

Dunham would be perfect.) Berlioz is immediately

obsessed with Smithson, and

writes to her with a marriage proposal—the first of

dozens of love letters. Rather

than taking out a restraining order, she simply leaves

Paris in 1829 without

ever acknowledging Berlioz’s existence.

Scene 2: Paris,

1830.

Berlioz has just completed the Symphonie

fantastique, an enormous five-movement

programmatic work, which details his

obsession with Harriet, including a drug-induced dream

sequence in which he

kills her and goes to Hell. The work is

controversial, but highly successful. Berlioz is happy

for the time being, and

has a new love interest, the pianist Camille Moke

(Gwyneth Paltrow).

Scene 3: Paris,

1832.

Berlioz, dumped by Camille, is despondent and

considering suicide.

Harriet is in town again, and an English gossip

columnist talks her into

attending a performance of the Symphonie

fantastique.

(The inspiration for Berlioz’s symphony is an open

secret, and her presence at

the concert is sure to stir things up...) Harriet savors

the attention, and

begins to pay some serious

attention

to Berlioz. The

two are married a year

later.

Epilogue.

Like most affairs based upon obsession, the

real thing turns out to be not as good as the fantasy. Within a year

of their marriage, Mr. and Mrs.

Berlioz are miserable.

They stick

together for ten unpleasant years, and are eventually

divorced in 1844. Berlioz

does not feel truly free of the

relationship until 1854, when Harriet dies.

He is married to his second wife a few weeks

later. [Note: I’m not making

any of this up! -

J.M.A.]

What You’ll Hear

The Symphonie fantastique is perhaps the

prototypical romantic program

symphony, the work that set the tone for many symphonies

and symphonic poems to

come. Not only is it intensely emotional, it is based

upon a distinct program:

a story Berlioz wants us to follow in the work.

The work that grew

out of

this strange affair, the Symphonie

fantastique,

is a landmark in the history of romantic music. Written

for a huge orchestra,

this work uses orchestral effects and even instruments

that had never been used

in a symphony. (This

is, for example,

the first appearance of the tuba—or rather its ancestor,

the ophicleide—in a piece

of orchestral music.)

Even more striking

is the programmatic idea behind Berlioz’s score. This is not

the first programmatic

symphony—Berlioz himself credits Beethoven’s “Pastoral”

symphony as

inspiration—but it is the first in which the

extra-musical story line is so

explicit. In

a story that has echoes of

Goethe’s dark Faust,

Berlioz

musically describes his obsession in great detail, even

going to the extent of

publishing a written program as an aid to the audience’s

imagination. To

illustrate his affair, he creates a

musical idée fixe

(literally “fixed

idea” or “obsession”) representing his changing view of

his beloved. This

idea appears in each movement, but each

time in a different character: as a flowing Romantic

melody in the opening

movement, as a lilting waltz in the second, as a

shepherd’s song in the third,

and in the fourth movement, it is the last thing the

condemned artist thinks of

before the blade of guillotine drops.

Its final appearance is as a mocking dance in the

“Witches’ Sabbath”

movement. The program Berlioz wrote to accompany the Symphonie Fantastique is as follows:

“Part I: Reveries—Passions.

The author

imagines that a young musician, afflicted with that

moral disease that a

well-known writer calls the vague des

passions, sees for the first time a woman who

embodies all the charms of

the ideal being he has imagined in his dreams, and falls

desperately in love

with her. Through

an odd whim, whenever

the beloved image appears in the mind’s eye of the

artist, it is linked with a

musical thought whose character, passionate but at the

same time noble and shy,

he finds similar to the one he attributes to his

beloved. This melodic image

and the model it reflects pursue him incessantly like a

double idée fixe. That is the

reason for the constant

appearance, in every moment of the symphony, of the

melody that begins the

first Allegro. The passage

from this state of melancholy

reverie, interrupted by a few fits of groundless joy, to

one of frenzied

passion, with its moments of fury, of jealousy, its

return of tenderness, its

tears, its religious consolations—this is the subject of

the first movement.

“Part II: A Ball. The

artist finds himself in the

most varied situations—in the midst of the

tumult of a party, in the peaceful contemplation

of nature; but

everywhere, in the town, in the country,

the beloved image appears before him and disturbs his

peace of mind.

“Part III: Scene in the

Country. Finding

himself one evening in the country, he hears in the

distance two shepherds

piping a ranz de

vaches [shepherd’s

song] in dialogue.

This pastoral duet,

the scenery, the quiet rustling of the trees gently

brushed by the wind, the

hopes he has recently found reason to entertain—all come

together to afford his

heart an unaccustomed calm, and in giving a more

cheerful color to his

ideas. He

reflects upon his

isolation; he

hopes that his loneliness

will soon be over.

But what if she were

deceiving him! This

mingling of hope and

fear, these ideas of happiness disturbed by black

presentiments, form the

subject of the Adagio. At the end,

one of the shepherds takes up the

ranz des vaches; the other no

longer replies. Distant

thunder—loneliness—silence.

“Part

IV: March to the Scaffold.

Convinced that his love is unappreciated,

the artist poisons himself with opium.

The dose of narcotic, too weak to kill him,

plunges him into a sleep

accompanied by the most horrible visions.

He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he

is condemned to death

and led to the scaffold, and that he is witnessing his own execution. The

procession moves forward to the sounds of a march that

is sometimes somber and

fierce, and sometimes brilliant and solemn, in which the

muffled sound of heavy

steps gives way without transition to the noisiest

clamor. At

the end, the idée fixe returns for a moment, like a

final thought of love before

the fatal blow.

“Part V: A Witches'

Sabbath. He sees

himself at the sabbath, in the midst of a frightful

troop of ghosts, sorcerers,

and monsters of every species, all gathered for his

funeral; strange noises,

groans, bursts of laughter, distant cries which other

cries seem to

answer. The

beloved melody appears

again, but it has lost its character of nobility and

shyness; it

is now no more than a dance tune, mean,

trivial and grotesque.

It is she, coming

to join the sabbath … a roar of joy at her arrival. She takes part

in the devilish orgy—funeral

knell—burlesque parody of the Dies irae—sabbath

round-dance—the

sabbath round-dance and the Dies

irae combined.”

_____

program notes ©2024 by J.

Michael

Allsen