Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

Overture Concert Organ Series

No. 3

February

20, 2024

J.

Michael Allsen

This third program of our Overture Concert Organ

Series

features Chelsea Chen, in a program dominated by French

music. She opens with the

brilliant Litanies by Jehan Alain, and then

presents arrangements of two

well-known piano miniatures by Debussy: The

Girl With the Flaxen Hair

and Arabesque No. 2. Ms. Chen plays her own Three

Taiwanese Folksongs

before closing the first half with a work by Maurice

Duruflé, Prelude

and Fugue on ALAIN: a powerful work written in

memory of the tragically

short-lived Jehan Alain. The second half opens on the

lighter note, with John Weaver’s

jazzy Variations on “Sine Nomine.” Next is a work by J. S. Bach, his impressive Prelude and Fugue in

D Major, written for the court of Weimar. Ms. Chen

closes

this program with a pair of virtuoso works by Louis

Vierne, Naïades

and the high-spirited Finale from his Symphony

No. 6.

Jehan Alain

(1911-1940)

Jehan Alain

(1911-1940)

Litanies

Jehan Alain was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye (now

effectively a western suburb of sprawling Paris), into a

highly musical family.

His father Albert was a composer and longtime organist at

Saint Germain’s

parish church, while his brother Olivier was a pianist,

composer and

musicologist, and his sister Marie-Claire was an

internationally-celebrated

organ soloist. After studying initially with his father,

Jehan became a student

at the Paris Conservatory in 1929, studying sporadically

there until 1939, when

he was awarded the first prizes in organ and

improvisation. He had to step away

from the Conservatory on a few occasions due to illness

and compulsory military

service in 1933-34. In the late 1930s, he earned his

living as an organist at a

small church in a northern Paris and at one of the city’s

synagogues. Alain’s

life was cut tragically short by World War II. In late

1939 he was mobilized

into the French army as a motorcycle dispatch rider. He

was one of the

thousands of French soldiers evacuated by the British

following Germany’s

invasion of Belgium in May 1940. Alain promptly returned

to France, rejoining

the army. He died in June 1940, during a single-handed

attack on a German

patrol. He was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre,

France’s highest

military honor.

Alain composed Litanies in 1937. It is a brilliant, sometimes exuberant piece, tied together by a short refrain heard at the beginning, which reappears in many forms during the piece. This form refers to the traditional Catholic litany, where a series of petitions are interspersed with a repeating chant response. A note Alain included in his manuscript describes its more personal intent: “When the Christian soul no longer finds new words in its distress to implore God’s mercy, it repeats ceaselessly and with a vehement faith the same invocation. Reason has reached its limit. Alone, faith continues its ascent.

Claude

Debussy (1862-1918)

Claude

Debussy (1862-1918)

The

Girl With the Flaxen Hair

(arr. Léon Roques)

Arabesque

No. 2 (arr.

Léon Roques)

As we have

heard before at these concerts, the colorful piano music

of Claude Debussy

translates beautifully to the organ. Ms. Chen next

presents a pair of

transcriptions by Debussy’s contemporary, Léon Roques. The

Girl With the

Flaxen Hair (La fille aux chevaux de lin)

comes from his first book

of piano Préludes, published in 1910. The title

refers to an 1852 poem

by Charles-Marie-René

Leconte de Lisle,

which begins:

Sur la luzerne en fleur

assise,

Qui chante dès le frais

matin?

C’est la fille aux

cheveux de lin,

La belle aux lèvres de

cerise.

[Seated

among the flowering alfalfa,

who is singing in the

cool morning?

It is the girl with the

flaxen hair,

the beauty with the

cherry lips.]

While Leconte de Lisle’s

poem is full of Romantic

description of the girl and the poet’s desire for her,

Debussy’s prelude is more

atmospheric: a wistful Impressionist portrait. A sinuous

melody above

shimmering harmonies leads to a slightly more

impassioned episode. Then, a

brief return of the opening melody introduces a serene

ending.

Among

his earliest published works, Debussy’s Two

Arabesques (1891) are among

his most frequently-performed piano works, and like The

Girl With the Flaxen Hair,

they have also been arranged for many different

instruments and ensembles. The

term “arabesque” refers to a design element in Islamic

art and architecture:

winding, intertwining lines based upon the natural

patterns of vines and

foliage. It is the perfect description of the ornate

figure heard at the

beginning of Arabesque No. 2.

Roque’s organ transcription makes the most of the work’s

capricious changes in

mood, from the playful opening, through a couple of

momentarily serious epodes,

a suddenly forceful coda, and a quiet, tongue-in-cheek

ending.

Chelsea Chen

(b. 1983)

Chelsea Chen

(b. 1983)

Three Taiwanese Folksongs

Ms. Chen provides the following note on her

work: “As a 2006-07

Fulbright Scholar to Taiwan, I researched Taiwanese folk

(vocal) music and

traditional instruments. I composed Three Taiwanese

Folksongs for a

concert at Grace Baptist Church in Taipei. Each of these

movements features

variations on a folk melody from the early 1900s. Four

Seasons is a song

about playful young lovers, The Cradle Song is a

soothing lullaby, and Song

of the Country Farmer describes the life of a

farmer in the southern part

of Taiwan. I wrote and performed these movements to help

introduce the pipe

organ to audiences in Taiwan. Their lilting, pentatonic

melodies are beloved by

the general public.”-

Maurice Duruflé

(1902-1986)

Maurice Duruflé

(1902-1986)

Prelude and Fugue on ALAIN

Born in Normandy, Maurice Duruflé studied at the

choir

school of Rouen cathedral before enrolling at the Paris

Conservatory at age 17.

His early training left him with a lifelong fascination

with plainchant, and

chant would eventually make its way into many of his later

compositions. He was

enormously successful as a student in Paris, eventually

winning first prizes in

organ, fugue, harmony, piano accompaniment, and

composition. Duruflé became the

assistant to Louis Vierne at the cathedral of Notre-Dame

de Paris in 1927, and

in 1929, he was named organist of the church of

St-Étienne-du-Mont, a position

he held for the rest of his life. He also served as

professor of harmony at the

Paris Conservatory from 1943-1970. A true perfectionist,

Duruflé finished

relatively few works in a 50-year career as a composer,

works that were often

revised many times.

One work that seems to have come to Duruflé

relatively

quickly, however, was his Prelude and Fugue on ALAIN. It was composed in

1942, in memory of

Jehan Alain: Duruflé dedicated the score “to

Jehan Alain, who died for

France.” To honor Alain, he used a device employed by many

composers, spelling

out a name in musical pitches. (There are, for example,

many works by Bach—and

later composers paying tribute to Bach—that use the

four-note motive B-flat -

A- C - B-natural as a musical signature.) In this case,

Duruflé invented a

simple cipher that transformed “Alain” into the pitches A

- D - A - A - F. This

motive appears throughout the work, as does a paraphrase

of the refrain used throughout

Alain’s Litanies. It has also been suggested that

Duruflé was influenced

by Debussy’s popular Arabesques in the prelude’s

melodic style.

The Alain motive is worked into the winding triplet

line

that dominates the Prelude. References to the Litanies

theme are

much more exposed, appearing over the restless triplet

lines, and the theme is

finally stated in its original form near the end. The more

solemn Fugue

is masterful…as one would expect from a composer who had

won the Conservatory’s

premier prix in fugue-writing. It is in fact a

double fugue, with the

Alain motive worked into the beginning of the opening

subject. A second subject

in sixteenth notes appears, and is eventually combined

with the first, in a

conclusion that ends with a thundering D Major chord.

John Weaver (1937-2021)

John Weaver (1937-2021)

Variations

on

“Sine Nomine”

Born in Pennsylvania, organist John Weaver trained

at

Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute and at the Union

Theological Seminary. He later

taught organ at the Curtis Institute (1972-2003), and also

served as head of

the organ department at New York’s Juilliard School

(1987-2004). In 1970, he

was appointed organist at the Madison Avenue Presbyterian

Church in New York

City, a position he held until his retirement in 2005.

Weaver continued an

active career as an organ soloist well into his 80s.

Weaver composed his Variations on Sine Nomine

in

1994, as the third movement of his Variations on Three

Hymn Tunes. The

Anglican hymn tune Sine Nomine (associated with

the All Saints Day hymn For

All the Saints) was one of the original melodies

Ralph Vaughan Williams

composed for the 1906 edition of The English Hymnal.

Weaver’s variations

on this foursquare, striding melody includes a witty

reference to the hymn tune

Sarum,

the rather stodgy

Victorian melody for All the Saints that Vaughan

Williams discarded. But

a third melody has the strongest influence, the American

traditional hymn When

the Saints Go Marchin’ In, heard first in the pedals

near the beginning. It

colors Weaver’s music even before it appears, however: the

Variations on

Sine Nomine

has a jazz-style swing

from beginning to end.

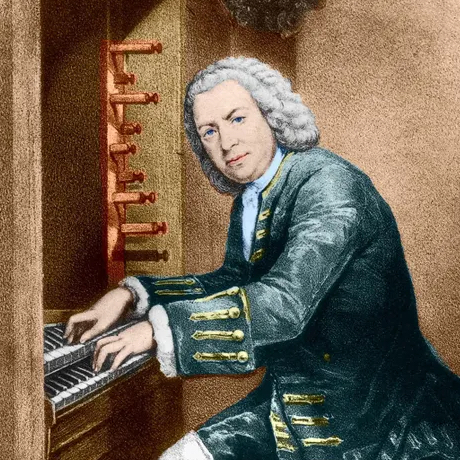

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Prelude and Fugue in D Major, BWV 532

Bach’s earliest professional position, at age 17,

was in Weimar, at the

court of Duke Johann Ernst III. Bach later described his

position as a “court

musician,” but the court records actually describe him as

a

“lackey”—low-ranking musicians were apparently also

expected to perform more

menial work as well. It is probably not surprising that

Bach left Weimar after

only six months to take a much more attractive position as

a church organist in

Arnstadt, where he worked from 1703-07. After serving in a

second organ

position in Mühlhausen (1707-08), he was lured back to

Weimar, where he would

remain until 1717, eventually serving as Konzertmeister

(music director). In his early years at Weimar,

Bach concentrated primarily on keyboard works. The court

chapel had a fine,

newly-renovated organ, and the Duke was apparently a great

fan of Bach’s organ

works. According to Bach’s obituary, the Duke’s

encouragement “fired him with

the desire to try every possible artistry in his treatment

of the organ.” Many

of the 48 preludes and fugues later published as The Well-Tempered Clavier were written

there, as were all but three

of the 46 Lutheran chorale preludes published in his Orgelbüchlein.

His Prelude and Fugue in D Major, BWV 532, written in about 1710, was one of the most

imposing works he composed in Weimar. (The bravura

style of this work made it a particular favorite of

Romantic pianists, and

there are transcriptions by Liszt and Busoni. There is

also a colorful

orchestral arrangement from 1929 by Respighi.) The opening

Prelude

unfolds in three sections, beginning with flashy scale

passages from pedals and

manuals, a hallmark of the north German style. The lengthy

middle section

explores a series of repeated motives in a dense,

constantly modulating

texture. A pause and dramatic rising flourish open the

concluding section, a

forceful ending that finally finds its way to D Major. The

subject of the Fugue

is a witty 16th-note figure in two parts that becomes

particularly impressive

when it is laid out on the pedals. Near the end, the

pedals have a short

cadenza sweeping up two octaves before a surprisingly

abrupt conclusion. One of

the 18th-century manuscript copies of this work includes

the remark: “In this

piece one must really let the feet kick around a lot.”

Louis Vierne

(1870-1937)

Louis Vierne

(1870-1937)

Naïades from Pièces de Fantasie, Op. 55, No.

4

Finale from Symphony No. 6 in B

minor, Op. 59

Though he was born nearly blind, Louis Vierne was

able to

study at the Paris Conservatory, where he became a devoted

disciple of César

Franck. At age 22, he became assistant organist to

Charles-Marie Widor at the

Parisian church of Sainte-Supplice, and in 1900 Vierne

became principal

organist at Notre-Dame de Paris, a position he held until

his death in 1937. Vierne

in fact died on the cathedral’s organ bench. On June 2,

1937, he was playing

what was scheduled to be his final public recital at

Notre-Dame, to an audience

of 3000. He had just finished one of his own works and was

getting ready to

play an improvisation on a theme that had been submitted

by a member of the

audience, when he suddenly lost consciousness and died,

victim a heart attack

or massive stroke. (His assistant, Maurice Duruflé, was in

the organ loft with

him.) Vierne was a fine composer and a phenomenal

improviser, but his vision

problems made getting his music down on paper increasingly

difficult, and he

would eventually write most of his works using Braille.

Despite this, his

catalog includes over 60 opus numbers published during his

lifetime—primarily

organ and piano music, but also several choral and

orchestral pieces. One

ongoing concern for Vierne was the state of Notre-Dame’s

enormous organ. The

famed builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll had rebuilt the

cathedral’s organ in the

1860s, but it was in poor repair by the turn of the

century, and Vierne worked

throughout his career to support its renovation, even

undertaking American

tours to raise funds. [Note: After several

renovations by Vierne and his

successors, Notre-Dame’s organ was completely rebuilt in

1992. The organ,

described by the group Friends of Notre-Dame de Paris as

the “largest organ in

France,” suffered only relatively minor damage during the

disastrous 2019 fire.

It is currently undergoing cleaning and restoration, and

plans are to have it

reinstalled in the cathedral later this year.]

Ms. Chen closes with a pair of Vierne works,

beginning with Naïades,

Op. 55, No. 4 (Water Nymphs) one of the

pieces in his fourth and

final suite of “fantasies” for organ, published in 1927.

(It was also one of

the pieces Vierne played on his final, fateful concert.)

It is a work combining

virtuosity—in the guise of a neverending, and distinctly

aquatic flow of 16th

notes—and a few tender Impressionistic moments.

Like several of his French colleagues, Vierne wrote

organ

symphonies designed both as virtuoso display pieces, and

works that would

showcase the largest organs of the day. His Symphony

No. 6, the last of

his organ symphonies, was completed in 1930, and dedicated

to the Canadian

organ virtuoso Lynwood Farnham. Farnham died later that

year, however, and the

work was premiered in 1934 at Notre-Dame by Duruflé. Its

fifth and final

movement, Finale, is heard here. After a couple of

brusque flourishes,

Vierne presents an exuberant, syncopated, and highly

chromatic refrain that

ties the movement together. There are a couple of

contrasting episodes: an even

more extravagantly chromatic passage, and a more relaxed

set of variations on a

quirky theme introduced on the pedalboard. The final

refrain becomes a wild

showpiece for the pedals.

________

program notes ©2024

by J.

Michael Allsen