Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

Overture Concert Organ Series

No. 2

November

11, 2023

J.

Michael Allsen

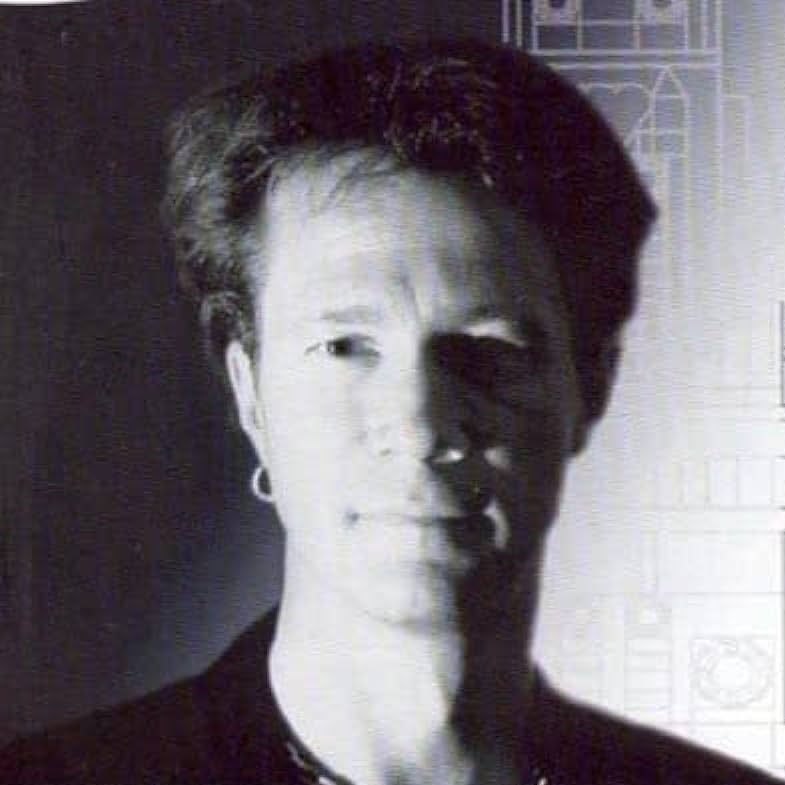

We welcome the

distinguished soloist

Ken Cowan for the second concert of this season’s organ

series. He and his

wife, violinist Lisa Shihoten, performed on this series in

2017. After opening

with a familiar work by Widor, he presents part of a

sonata by Widor’s British

contemporary Edward Elgar. Rounding out the first half are

a profouynd work by

Rachel Laurin based upon plainchant and an impressive

showpiece for pedals by

George Thalben-Ball. The second half opens with music by

Bach, his enormous Prelude

and Fugue in E minor. Next

are a pair of smaller pieces: a spirited work by Swedish

composer Gunnar

Idenstram, and a quiet, reflective piece by William Grant

Still. To close, Mr.

Cowan presents his version of a stunning virtuoso piano

work by Liszt, the Mephisto

Waltz No. 1.

Charles-Marie Widor

(1844-1937)

Charles-Marie Widor

(1844-1937)

Symphony No. 6 in G minor, Op. 42, No. 2 -

movement 1, Allegro

Charles-Marie Widor had

a long career as one of France’s greatest organists,

beginning with his

appointment at age 25 as organist at the church of

Saint-Sulpice in Paris, a

position he would hold for some 64 years. In 1890, he also

succeeded César

Franck as organ professor at the Paris Conservatory, where

he would be a

powerful influence over the next generation of French

organists and organ

composers. As a composer, Widor wrote four operas and a

host of works for

orchestra, chorus, and chamber ensemble, but it is his

organ works that are

known today. Particularly popular are his ten symphonies

for solo organ. These

are large multimovement works designed to exploit the vast

range of timbres

available on a new generation of large organs, pioneered

in the 19th century by

organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. The organ Widor

played at Saint-Sulpice,

rebuilt

by Cavaillé-Coll in 1862, is widely considered to be the

builder’s masterpiece.

Widor’s Symphony

No.6 is one of four

organ symphonies he published in 1879 as his Op 42. Widor

played its premiere

on August 24, 1878, at the inauguration of a magnificent

new Cavaillé-Coll

instrument installed in the Palais de Trocadero, a Paris

concert hall. Its

opening Allegro

is among his more

frequently-played works today. It opens with a thundering

chorale theme that

serves as the basis for a free set of variations. Widor’s

dense, sometimes

intensely chromatic counterpoint throughout testifies to

his devoted study of

J. S. Bach.

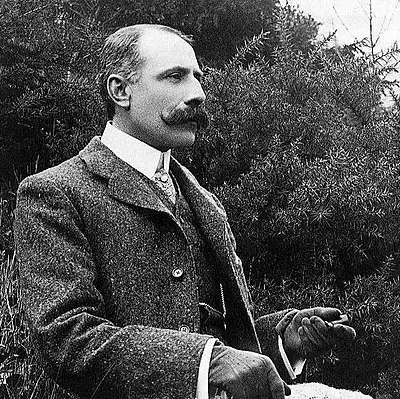

Edward Elgar

(1857-1934)

Edward Elgar

(1857-1934)

Sonata in G, Op. 28 - movements 3 and 4

The great British composer Edward Elgar was the son

of a

church organist, and eventually succeeded his father as

organist at Saint

George’s Catholic Church in Worcester. Many of his closest

friends and

colleagues served as organists at England’s great

cathedrals, including William

Done, Hugh Blair, and Ivor Atkins at Worcester, and George

Robertson Sinclair

at Hereford. (Sinclair—together with his bulldog Dan!—was

among the close

friends Elgar would celebrate in his 1899 Enigma

Variations.) However, Elgar wrote only a few works

for organ, and the Sonata

in G heard here is certainly the

most substantial of them. (What is sometimes known as the

Sonata No. 2, was actually an arrangement by

Ivor Atkins of a suite

Elgar had written for brass band in 1930.) Elgar composed

the work in 1895 for

Hugh Blair, possibly for the dedication of a new organ at

Worcester Cathedral.

This enormous instrument, designed by Robert Hope-Jones,

was actually a

combination of two large organs already in the church, and

Elgar’s sonata was

designed for the vast range of stops it had available.

Blair’s premiere of the

work on July 8, 1895 was disappointing: a friend of the

composer wrote that he

had “made a terrible mess of poor Elgar’s sonata.” Though

there were rumors

that Blair was drunk at the time, the quality of the

performance probably had

more to do with the fact Elgar had sent him the score for

this very challenging

piece only four days before the performance!

The Sonata

in G is

laid out in four movements, the last two of which are

played here. The slow

movement (Andante

tranquillo) has a

lovely, flowing main theme, that sounds like an elder

sibling to the famous Nimrod movement

in the Enigma

Variations. (The Andante tranquillo

theme comes from an

earlier sketch for a cello piece titled Dreams.)

There is a brief hint of tragedy in the middle of the

movement, before the

hushed theme returns. The final movement (Presto

(Comodo)) is

set in sonata form,

beginning with a restless main theme. The contrasting idea

is marchlike, but

reserved. At the beginning of the development section,

Elgar brings back the

third movement’s main theme. This melody reappears at the

end, after the

recapitulation, as an introduction to the forceful coda.

Rachel Laurin (1960-2023)

Rachel Laurin (1960-2023)

Poème symphonique

pour le temps de l’Avent, Op. 69

Rachel

Laurin died earlier this year, on August 12, a few days

after her 62nd

birthday, following a long battle with cancer. One of

Canada’s leading

organists and composers, she was born in Québec. After

studies at the Conservatoire

de musique du Québec à Montréal, she took a position as

organist at the Oratoire Saint-Joseph du Mont-Royal,

Montreál—the

famous basilica which stands at the highest point in the

city—and she later

became an improvisation instructor at the Conservatoire.

Laurin maintained a

busy, international career as a soloist, and was a

prolific composer: she wrote hundreds of works for

organ and other solo instruments, voice, choir, and

orchestra.

Laurin

composed the Poème

symphonique pour le

temps de l’Avent (Tone Poem for the

Advent Season) in 2013, for organist Isabelle

Demers. (Demers played a

memorable concert, including another work by Laurin, in

Overture Hall in March

2022.) Demers premiered the Poème

symphonique on December 1, 2013, on the

newly-installed organ in the

concert hall of Québec’s Palais Montcalm. The work is

based upon the Latin

plainchant hymn Creator

(or Conditor) alme siderum from the Vespers service for

the first Sunday in

Advent. The Poème

symphonique is a

free set of variations on this melody, and Laurin also

works in references to a

Kyrie chant

associated with Advent. However,

the piece has deeper significance: throughout the score

Laurin included cues

that show it to be a spiritual journey. It begins with a

delicate texture she calls

“World of Stars.” After

a powerful transition

based upon the hymn, the texture thins for a quiet version

of the Kyrie: a

supplicative part of the Mass that is labeled “Our Pleas.”

This grows more

intense in a passage called “The Universal Sin,” and

breaks into angular music

identified as “Satan’s Snare” and a fierce passage for

pedals for “A World of

Sickness.” There is a turbulent battle, labelled “Power,

Divine Glory,”

continuing through “Our Prayers.” The texture thins for a

quiet, almost

dancelike version of the hymn (“Virginal Shrine, Victim

Without Stain” and “By

an Act of Love, to Cure Our Ills”). Here Laurin is quoting

a setting of Conditor

alme siderum by the early

15th-century composer Guillaume Du Fay. The “World of

Stars” of the opening

returns, and there is a statement of the Kyrie

(“Our Prayers” and “Great Judge of All: Defend Us From Our

Foes”) The bold climactic

section that follows, labeled “Power, Honor, Praise and

Glory,” is meant to

represent the verse:

Come in thy

holy might, we pray;

Redeemer us for eternal day

From ev’ry pow’r of darkness,

when

Thou

judgest all the sons of men.

The piece closes

with a hushed version of the opening “World of Stars”

music, now marked “Amen.

From Age to Age, Eternally.”

The journey

ends with a luminous C Major chord: “In Heaven, and Among

Mortals.”

George Thalben-Ball

(1896-1987)

George Thalben-Ball

(1896-1987)

Variations on a Theme of Paganini

There is a long tradition of virtuosos writing

their own

music: works that exploit their specialized knowledge of

their instrument, and

their own technical and expressive abilities. The

tradition predates the early

19th-century violinist Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840), but

it was Paganini who

set the mold for many virtuosos to follow. Most of his

music was composed to

display his own impressive technique, including the

ironically-named 24

Caprices for Solo Violin he published

in 1819. “Caprice” implies a fairly

lightweight bit of music, but there is nothing light or

easy about these

pieces, which employ an astonishing battery of virtuoso

violin techniques. The

last and most famous of them all, No.24,

included a theme and a dozen increasingly awe-inspiring

variation. Paganini’s

simple theme became a kind of musical touchstone for the

idea of virtuosity,

and since the early 19th century, Chopin, Brahms, Ysaÿe,

Rachmaninoff and

dozens of other composers have used its theme the basis

for their own virtuoso

works.

The

Australian-born

organist George Thalben-Ball traveled to London

at age 14 to study at

the Royal College of Music, and spent the rest of his

career in Britain. In

1923, he became organist of London’s Temple Church, a

position he held until

his retirement in the early 1980s. In 1949, he was

additionally appointed

organist of the City of Birmingham and Birmingham

University. Thalben-Ball was

a well-known virtuoso with phenomenal technical abilities.

His contribution to

the Paganini

Variations tradition

dates from 1962. Its ten variations, played entirely on

the pedals, are, true

to the tradition, increasingly impressive: calling for

wildly rapid figures, glissandos, and

for two-, three-, four-

and (in the astonishing Variation 10) six(!)-part

harmony.

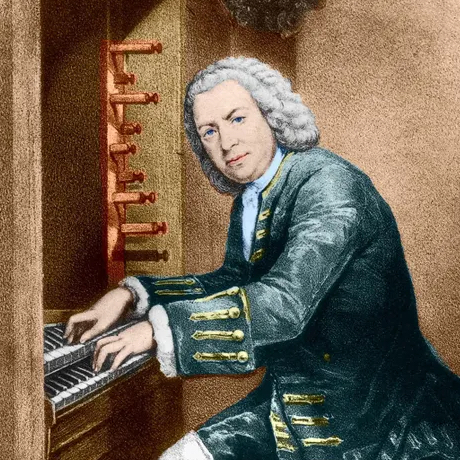

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Prelude and Fugue in E minor, BWV 548 (Wedge)

In 1723, Bach arrived in Leipzig to become Kantor

at the Thomaskirche: a

challenging position that involved not only leading the

music at Leipzig’s

central church, but supervising the music at all of the

city’s main churches,

and teaching the boys at the city’s choir school. Bach

threw himself into the

position with tremendous vigor, most notably completing

five annual cycles of

cantatas for the Thomaskirche, some 300 works in all. By

1728, however, his

enthusiasm for the weekly grind of work as Thomaskantor

seems to have faded.

That year, he became the director of the Leipzig collegium

musicum, a group of

amateur musicians who gave informal concerts in one of the

city’s coffee

houses. Bach clearly relished the chance to return to

secular music-making, and

he devoted much of his compositional energy to this group,

writing new works,

and adapting pieces he had written during his earlier jobs

at Cöthen and

Weimar. At the same time, he also became more active as a

recitalist. Though he

was not employed specifically as an organist in Leipzig,

Bach already had a

reputation as one of Germany’s great organ virtuosos, and

he occasionally

played out-of-town concerts through the rest of his

career. Though they are not

well-documented, he probably gave public organ recitals in

Leipzig as well,

most likely on the relatively new organ at the

Paulinerkirche. At least some of

the masterful organ works he wrote late in his career,

including the truly

impressive Prelude

and Fugue in E minor,

composed sometime between 1727 and 1732, may have been

written with these

public concerts in mind.

The massive Prelude

is laid

out in a way that resembles contemporary concerto

movements: it begins with a

stern passage that serves as a ritornello:

an idea that is repeated several times during the course

of the moment, both to

tie the piece together and to serve as a springboard for

new, contrasting

ideas. The equally massive Fugue,

some 231 measures long, is Bach’s longest fugue, and

certainly one of his most

spectacular essays in this form. Its subject gave this

fugue its nickname.

Heard unaccompanied at the beginning of the fugue, the

subject begins on the

note E, and the theme that follows expand gradually above

and below that pitch,

creating a kind of musical “wedge.” After exploring this

subject thoroughly in

fugal style, Bach inserts a huge episode (a section of a

fugue where the

subject is not present): freeform and flashy passages that

resemble an

improvised toccata. The ending is largely an identical

repeat of the opening

section.

Gunnar Idenstam (b.

1961)

Gunnar Idenstam (b.

1961)

Scherzo II (Yoik) from Cathedral

Music

The Swedish organist, composer, and folk musician

Gunnar

Idenstam channels a wide variety of influences in his

work, from music by Bach

and Dupré, to classic 1970s Rock, Heavy Metal, and Pop (he

has collaborated

with ABBA’s Benny Anderssen), New Age music, and folk

styles from throughout

Sweden. Mr. Cowan presents a selection from Idenstam’s

17-movement Cathedral

Music, composed in 1995-96.

The Scherzo

heard here is based upon

a musical tradition of the Sámi, an indigenous people who

live in the tundra

that stretches across of the northern reaches of Norway,

Sweden, Finland, and

the Kola Peninsula in northwest Russia. (Idenstam was born

in this far northern

part of Sweden.) The yoik is an

ancient Sámi song form: freeform, often improvised, and

usually wordless. For

the Sámi, a yoik

is a deeply

meaningful expression of a soul: of a person, an animal, a

tree, or any part of

the environment. Ancestors can be addressed through a yoik, and each Sámi child receives his or

her own yoik.

Idenstam’s Scherzo is a sometimes playful piece that he

describes as follows:

“[It] is based on a song (yoik) from

Lapland, accompanied by lively triplet figures and New Age

harmonies. The

rhythm is gradually shifted from 6/8 time to popular waltz

time and then back

to 6/8 time.”

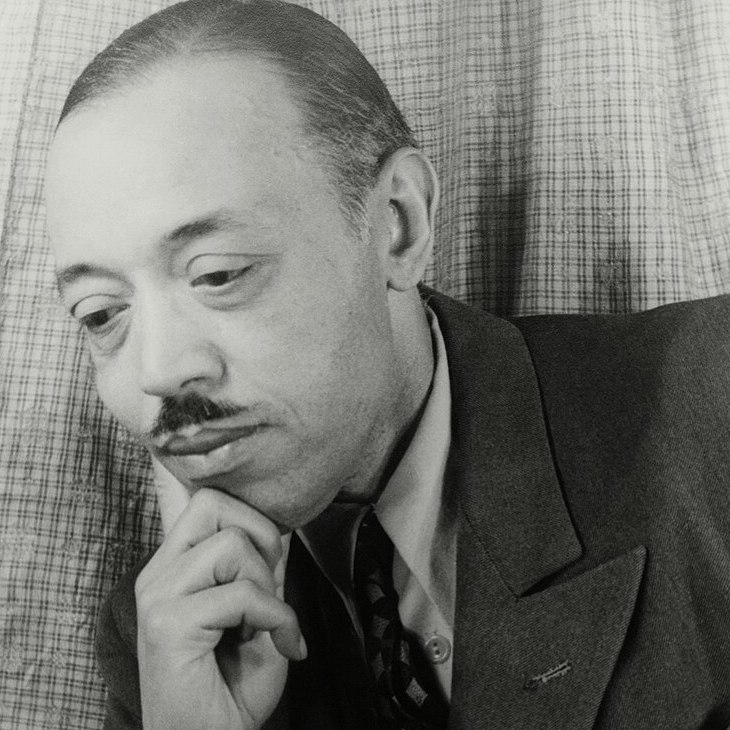

William

Grant Still

(1895-1978)

Reverie

Reverie

William Grant Still, who would eventually be known

as the

“Dean of African-American composers,” was born in a small

town in Mississippi.

He studied music at Wilburforce University in Ohio, but

had to withdraw in

order to earn a living. Still worked as an arranger for

the early blues

composer W. C. Handy, and was eventually able to enroll at

Oberlin College,

though his college study was again cut short, this time by

service in the Navy

during World War I. After the war, Handy invited him to

New York City, where he

spent the next several years earning his living as an

arranger: writing music

for Handy and other popular singers and bands, and doing

orchestrations for

Broadway shows. Still’s breakthrough work in what he

referred to as “serious

music” was his Afro-American

Symphony,

a work that incorporated the blues, spirituals and other

Black musical idioms.

With its October 1931 premiere by the Rochester

Philharmonic Orchestra, it

became the first work by a Black composer to be programmed

by a major American

orchestra. In 1934, Still relocated to Los Angeles, where

he would spend the

rest of his life. He worked occasionally scoring music for

Hollywood and,

later, television, and had a successful career working as

an independent

composer. Still left behind an impressive musical legacy

of concert music: five

operas, four ballets, five symphonies, eight symphonic

poems, and a host of

smaller works for orchestra, chamber ensembles, chorus,

and solo voice. His Reverie,

written in 1962 for a commission

by the American Guild of Organists, is one of only two

works Still wrote for

organ. It is a brief and introspective work, whose main

theme subtly evokes the

feel of a Black spiritual.

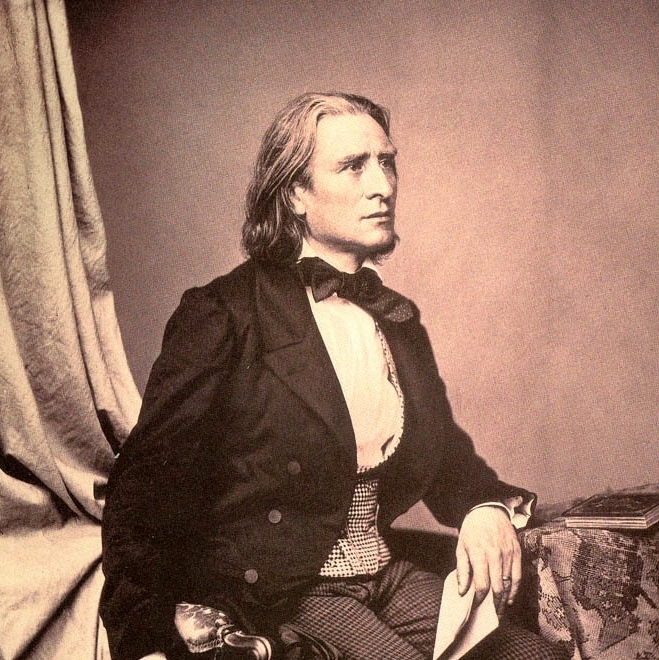

Franz Liszt

(1811-1886)

Franz Liszt

(1811-1886)

Mephisto Waltz. No. 1 (The

Dance in the Village Inn), arr. Ken Cowan

Franz Liszt was the preeminent piano virtuoso of

the 19th

century. He was also an imaginative and ground-breaking

composer, but as a

young man, he was so much in demand as a soloist that he

had little time to

develop his composing skills. Liszt’s concert tours in the

1830s and 1840s were

nothing short of phenomenal—contemporaries used the term

“Lisztomania” to

describe the frenzy surrounding his playing. He performed

hundreds of concerts

to packed houses throughout Europe, and produced for the

most part compositions

that focused on his own technical showmanship, rather than

musical content. It

was not until he settled in Weimar in 1848, taking a

secure and stable job as

music director to the Weimar court, that Liszt’s music

took a turn away from

these showy pieces. Among other experiments, he began to

explore the idea of

program music: works that tell a story or which are based

upon poems,

paintings, or other nonmusical inspirations. Most famous

are a series of

symphonic poems written in Weimar, but he also wrote

programmatic works for

piano. Like many Romantic

artists, Liszt was fascinated with the legend of Faust,

most familiar in

Germany in the versions by Goethe and Nikolaus Lenau.

This is the dark story of

the scholar Faust, who makes a deal with the Devil

(Mephistofeles), exchanging

his soul for universal knowledge and the pleasures of

the world.

Between

1856 and 1861, Liszt sketched out an orchestral piece, Two Episodes from Lenau’s Faust, at the

same time producing a solo

piano version of the second part, Dance

in the Village Inn. He published this piano piece

in 1862 as the first of

four Mephisto

Waltzes he would write

over the next 20 years, The Mephisto

Waltz No. 1, heard here in an adaptation for organ

by Mr. Cowan, depicts

the part of the story where Faust and Mephistofeles walk

into an inn.

Mephistofeles picks up a fiddle and begins to play a

dance tune, bewitching the

people in the inn, including Gretchen, who is then

seduced by Faust. This is no

typical lilting and pretty 19th-century waltz, but a

series of fierce,

aggressive dances that show the Devil whipping the

customers at the inn into a

frenzy. In the middle there are a couple of slower,

seductive episodes, (marked

expressivo amoroso)

before Liszt

returns to the wild character off the opening. At the

very end there is a

mysterious episode that shows Faust leading the innocent

Gretchen away, before

the piece ends in a ferocious coda.

________

program notes ©2023

by J.

Michael Allsen