Madison Symphony

Orchestra Program Notes

May

3-4-5, 2024

98th Season /

Subscription Program 8

J.

Michael Allsen

We

close this

season with the Madison Symphony Orchestra’s first-ever

all-Mexican program, beginning

with José Pablo Moncayo’s Huapango,

a joyful take on a folk dance from the state of Veracruz.

Making his debut with

the orchestra, the distinguished Mexican-born pianist

Jorge Federico Osorio

performs the lush, romantic

Piano

Concerto No.1, an early work by the Mexican master

Manuel Ponce. We then

perform the colorful—and sometimes savage—Night

of the Mayas by Silvestre Revueltas. This work will

be coordinated with

projected images assembled by the MSO’s Peter Rodgers. And

as the gran final

of this fiesta, we welcome the famed Mariachi de los

Camperos for an

exuberant set of mariachi music!

This lively work, Moncayo’s most popular

piece, is based upon the folk music of Veracruz.

This lively work, Moncayo’s most popular

piece, is based upon the folk music of Veracruz.

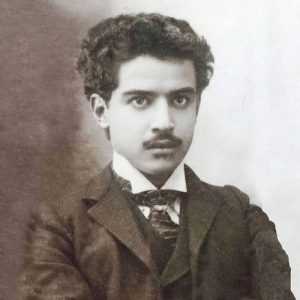

José Pablo Moncayo

Born: June 29,

1912, Guadalajara, Mexico.

Died: June 16,

1958, Mexico City, Mexico.

Huapango

•

Composed:

1941.

•

Premiere:

August 15, 1941 in Mexico City,

by the Orquestra Sinfónica de Mexico,

under the direction of Carlos Chávez.

•

Previous

MSO Performances: This is our first performance of

the work.

•

Duration:

9:00.

Background

Though he had a

lamentably short career, composer José Pablo Moncayo

became one of Mexico’s leading musical figures.

Moncayo

trained in Mexico City, and became a protégé of the great

Mexican composer Carlos Chávez, but was closely associated

with the more radical Silvestre Revueltas as well. Moncayo

also studied briefly with Aaron Copland in the United

States. While still a student in Mexico City, he started

his career as a percussionist in Orquestra Sinfónica de Mexico (Symphony

Orchestra of Mexico), and he would eventually succeed

Chávez as conductor, leading the orchestra from 1949-1954.

In the 1930s, Moncayo was part of the “Group of Four”—an

influential group of like-minded young nationalist

composers who stated aim was to forward the cause of

classical works based on Mexican musical material. By far

his most popular work is the Huapango,

composed in 1941 for a commission by Chávez. Moncayo

completed the work that summer while attending the

Tanglewood Festival near Boston, at the invitation of

Copland and conductor Serge Koussevitsky.

What You’ll Hear

The fast-paced

opening and closing sections are based upon a pair of

songs from Veracruz, and the more relaxed middle section

adapts a third.

The title Huapango refers

to a folk dance associated with the son huasteca—the

lively folk music of the Mexican coastal state of

Veracruz. The huapango

is traditionally danced on a low wooden platform, so that

the dancers’ footwork can provide a percussive

counterpoint to the son.

There is a large repertoire of traditional sones, but good

singers—huasteceros—will

seldom

sing a son huasteca

the same way twice: changing melodies at will and

inserting topical references and joking asides to their

audience. In 1940, Moncayo and his friend Blas Galindo

took a folk song collecting trip to the coastal city of

Alvarado in Veracruz, and Mocayo transcribed versions of

three songs that he later adapted in his Huapango. The

bold opening section is based on two songs, El siquisiri an El balajú, with

the lively alternation between duple and triple meters

that characterizes much of Mexican folk music. A slightly

slower, more stately contrasting section adapts El gavilán, but

the tempo soon

ratchets up for a wild reprise of the opening music.

This early work by Mexican composer

Manuel Ponce helped to

establish him as a leading figure in his homeland.

This early work by Mexican composer

Manuel Ponce helped to

establish him as a leading figure in his homeland.

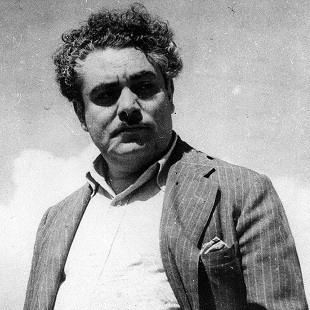

Manuel

Ponce

Born:

December

8, 1882, Fresnillo, Mexico.

Died:

April

24, 1948, Mexico City, Mexico.

Piano Concerto No. 1 (Romántico)

• Composed: Ponce

completed the work in September 1910.

• Premiere: July 7,

1912 in Mexico City, with Ponce as soloist, conducted

by Julián Carillo.

• Previous MSO

Performances: This is

our first performance of the work.

• Duration:

23:00.

Background

Written

shortly after he returned from studying in Europe no

concerto is largely European in style, reflecting in

particular the influence

of Franz Liszt.

Born in

the north

central state of Zacatecas, Ponce studied music

initially with his sister,

before moving to Mexico City as a teenager to enter

the National Conservatory.

While there, his harmony teacher, Eduardo Gabrielli,

strongly encouraged Ponce

to continue his studies in Europe. He traveled to

Europe in about 1904,

studying in Milan and later in Berlin, where one of

his primary influences was

the pianist Martin Krause (who had been a disciple of

Franz Liszt). Out of

money, Ponce returned to Mexico in 1907, and

immediately threw himself into the

musical life of Mexico City, taking a teaching post at

the National

Conservatory. In the early 20th century, classical

composers across Latin

America were beginning to look towards their own

national styles for

inspiration. In Mexico, Ponce was quickly recognized

as a leading figure,

particularly after a July 1912 concert in Mexico City

that featured his Piano

Concerto No. 1, as well as several smaller

pieces that were based upon

Mexican folk styles. He followed this up with an

influential lecture on Mexican

music in 1913. From his post at the National

Conservatory (He became its

director in 1933.), and his work as a composer,

performer, musicologist, and

music critic, Ponce exerted a tremendous influence on

Mexican music for

decades.

Ponce’s Piano

Concerto

No. 1, his first large-scale composition and

only the third piano

concerto written by a Mexican composer, was quickly

nicknamed the “Concierto

Romántico.” In comparison to the more distinctly

“Mexicanist” music that

dominated his career as a composer, this is largely a

romantic, German-style

concerto influenced by Franz Liszt (by way of Ponce’s

teacher Krause), Franck,

and Chopin. However, many later Mexican writers have

pointed out subtle traces

of folk styles from his homeland.

What

You’ll Hear

In

this work, the traditional three movements of a romantic

concerto are brought together into a single, unbroken

span:

•

a stormy opening section in sonata form,

•

a lyrical interlude ending with a long cadenza, and

•

a lively conclusion

The concerto is laid out in three interconnected

movements,

beginning with a section marked Allegro

appassionato.

Written in a loosely-constructed sonata form, it begins

with a tragic main idea

from the orchestra. When the piano enters, it is with a

dramatic solo passage

and a long trill before it turns to the main theme.

Piano and solo woodwinds

introduce a lighter second idea before a stormy

development that focuses

primarily on the main theme. A short recapitulation of

this idea ends with a

short transition from the woodwinds leading into the

second movement (Andantino

amoroso). This section, the longest of the

concerto, begins with a lush

introduction, which the piano picks up in a passionate

solo. The middle section

is a sentimental pair of conversations where the piano

is answered first by

strings and then by English horn. (This passage is often

described as a

reference to a Mexican-style love duet.) A long solo

cadenza, referring to all

of the main ideas heard so far, leads into the final

section (Finale: Allegro).

This serves as an extended coda, ending with a dramatic

piano flourish.

This work is an adaptation of a film score

by Revueltas, assembled 20 years after his death.

This work is an adaptation of a film score

by Revueltas, assembled 20 years after his death.

Silvestre Revueltas

Born: December

31, 1899, Santiago Papasquiaro, Mexico.

Died: October 5,

1940, Mexico City, Mexico.

La noche de las

Mayas (The

Night of the Mayas), arr. José Ives Limantour

•

Composed:

1939.

•

Premiere:

This music was originally

written for a 1939 film. The suite heard here was

prepared by José Ives Limantour in 1960. Limantour also

directed the first performance on January 30, 1961, by

the Orquestra Sinfónica de Guadalajara.

•

Previous

MSO Performances: This is our first performance of

the work.

• Duration: 26:00.

Background

Revueltas was a

radical—musically and politically—and created a style that

was influenced by both Mexican music and European

modernism. This clearly heard in his score to La noche de las Mayas,

which was among his final works.

Born into an

artistic family in the Mexican state of Durango, Silvestre

Revueltas trained as a violinist, composer, and conductor

in Mexico and the United States. In the late 1920s he

became a protégé of Mexico’s leading musical figure,

Carlos Chávez. When Revueltas was not yet 30, Chávez

invited him to become assistant conductor of Orquestra Sinfónica de Mexico.

After a promising start, the end of his career was much

darker. He broke with Chavez in 1936, and briefly directed

a rival national orchestra. In 1937, Revueltas left for

Spain to lend his support to anti-fascist forces in the

Spanish Civil War. He eventually fled back to Mexico when

Francisco Franco’s fascists seized total power in Spain.

Though he continued to compose, his last few years were

marked by increasing depression, poverty, and alcoholism.

He died of pneumonia at age 40. Though relatively little

known for many years after his death, Revueltas’s unique

music has enjoyed a resurgence in the past few decades.

As a

composer, Revueltas was much more interested in

contemporary European styles than most of his Mexican

contemporaries. His orchestral and chamber music was often

a blend of modernist techniques with a huge array of

Mexican musical influences. He brought this same approach

to several film scores written between 1935 and 1939. The

last of these was for the 1939 film La noche de las Mayas,

directed by Chano Uruete. This was a drama centering on an

isolated community of Maya Indians in Mexico’s Yucatán

jungle, and the disastrous result of their encounter with

modern culture, in the guise of a white explorer who finds

the tribe. Revueltas’s score uses a variety of indigenous

melodies, and a range of percussion instruments from the

region. Revueltas died before he could create a concert

version of this music. German composer Paul Hindemith

created a concert suite from selections from Revueltas’s

score in 1946. However, the 1960 version by conductor José Ives Limantour is how the

score is usually heard today. Limantour took a very free

hand in arranging over 30 of Revueltas’s brief musical

cues for the film into a large four-movement suite. The

suite uses a fairly standard orchestra but an enormous

percussion battery in the final movement, requiring

twelve players. It calls for several indigenous

instruments, including caracol (conch

shell), sonajas

(metal rattles), teponaxtles

(large hollow wooden “slit drums”), and huehuetl (a

large bass drum).

What You’ll Hear

This concert

suite, arranged by José Ives

Limantour, is in four movements:

• Noche de los Mayas begins

and

ends calmer episode in the middle of the movement.

• Noche de los Jarana

is more lighthearted, set above a dance rhythm.

• Noce de Yucatán is

a calm piece of “night music” with hints of darkness.

• Noche de

encantamiento is where Limantour unleashes the full

percussion battery. Most of the movement is a series of

variations on a theme heard at the opening.

The opening

movement, Noche de

los Mayas, begins

with a threatening fanfare—1930s “movie music” of the most

dramatic kind. This is followed by a more relaxed episode

and quietly repetitive music from the woodwinds that

evokes indigenous melodies. The movement ends with a

reprise of the opening music. Noche de los Jarana

is a much lighter scherzo. (Jarana is slang

for a drunken party.) The frantic forward motion never

stops, as music flits between various meters. The strings

act as timekeepers, as brass and woodwinds interject

contrasting ideas: a mournful conch-shell call from the

tuba, a brief attempt to upset the strings’ rhythm, and a

slightly tipsy but quick-footed dance from the brass. Noce de Yucatán

begins with lyrical and sometimes tense music, evoking the

surrounding jungle. This is interrupted briefly by a short

interlude for solo flute and drums: an indigenous melody

borrowed by Revueltas. The opening mood returns at the

bend, but is shattered by a sudden percussive crack that

begins the last movement, Noche de

encantamiento (Night

of enchantment). The oboe lays out a theme used

throughout the movement, followed by an angry response

from the strings and brass. The rest of the movement is a

set of four increasingly ferocious variations on the

opening theme, dominated entirely by the percussion. These

percussion parts, meant to sound improvised, were added by

Limantour, and are not part of Revueltas’s film score. The

movement ends with a savage coda.

________