Madison Symphony

Orchestra Program Notes

April 12-13-14, 2024

98th Season /

Subscription Program 7

J.

Michael Allsen

Verdi’s Requiem is one of

the

great sacred works of the 19th century, and one of the

most dramatic settings

of the Mass for the Dead.

Verdi’s Requiem is one of

the

great sacred works of the 19th century, and one of the

most dramatic settings

of the Mass for the Dead.

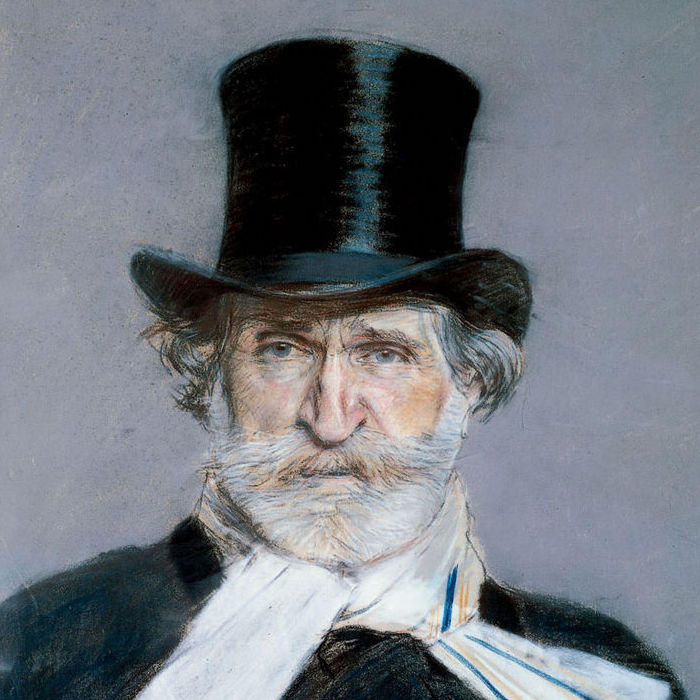

Giuseppe Verdi

Born: October

10, 1813, Le

Roncole, Italy.

Died:

January 27, 1901, Milan, Italy.

Messa da Requiem

•

Composed:

In

1868 and 1873.

•

Premiere:

Verdi conducted the first

performance in Milan on May 22, 1874.

•

Previous

MSO Performances: 1936,

1937, 1945, 1954, 1965, 1978, 1991, 2002, and 2009.

•

Duration:

83:00.

Background

This huge work is

Verdi’s contribution to a centuries-old tradition of Requiem settings.

It had its roots in an

unsuccessful attempt to memorialize composer Gioacchino

Rossini. Verdi

eventually completed the Requiem in honor

of the poet Alessandro Manzoni.

The Latin text of the Requiem, or

Mass for the Dead, has

provided composers with inspiration for over 500 years.

The first polyphonic

settings of the text were composed in the 15th century,

and there is an

unbroken tradition of Requiems that

continues down to our own day: there are literally

thousands of settings of the

complete Mass for the Dead, or its individual movements.

In the Catholic

liturgy prior to the Vatican II reforms, the Latin Requiem was sung at burial services and on

All Soul’s Day (November

2), in remembrance of the faithful dead. The chant texts

that comprise this

Mass were complete by the 14th century, and they provide

a rich source of

imagery and emotion. At the heart of the Requiem

is the lengthy sequence Dies irae,

which was written by the 13th-century monastic poet

Thomas of Celano. This text

dwells on the terror and destruction of the Day of Judgment foretold in the Book of

Revelations, and the petitioner interjects forlorn

prayers for safety from the

Lord’s wrath. After the horror of the Dies

irae, the texts become more comforting in nature.

The offertory Domine

Jesu Chiste offers prayers for

the dead, and recalls the promise of redemption. The

gentle imagery of the Lux aeterna, a

further prayer for

intercession, celebrates the merciful Lord. The final

movement, Libera

me, speaks with the most personal

voice of all the Requiem

texts: the

petitioner prays directly to the Lord, expressing fear

and hope for

deliverance.

Verdi’s monumental setting of the Requiem began

in 1868, the year of

Gioacchino Rossini’s death. Verdi, who called Rossini as

“one of the glories of

Italy,” proposed a musical tribute by Rossini’s

colleagues: a Requiem

Mass, whose individual sections

would be composed by thirteen leading Italian composers.

Verdi reserved the

final section, the Libera me, for

himself, and assigned the remaining sections of the Mass

to the other twelve

composers according to an overall tonal and textural

plan. Nearly all of the

twelve were influential church musicians, though most

had written for the

stage, as well. (For the most part, they are forgotten

today.) The project was

completed early in 1869, when all of the individual

movements were gathered in

Milan, and submitted to Verdi’s publisher, Ricordi.

Verdi’s original proposal

was to have the Messa

per Rossini

performed in Bologna, on the first anniversary of

Rossini’s death. After this

first and only performance, the score would be sealed

and placed in the vault

of Bologna’s Music School as a monument to Rossini, who

had spent much of his

career in that city.

This grandiose plan fell victim to

a lack of available funds and to Italian musical

politics: the opera partisans

in Bologna would have nothing of a proposal that

originated in the rival city

of Milan! The projected concert was never arranged, and

Verdi was soon too busy

with the production of his opera Aïda

to make his own arrangements for a performance of this

musical patchwork. He

set aside the Messa

per Rossini,

although he showed his completed score for the Libera me to his colleague Alberto

Mazzucato. Mazzucato urged Verdi

to abandon the opening twelve sections, and complete the

Requiem himself, suggesting that, by

itself, the Libera

me contained enough musical

material to generate an entire Mass.

Alessandro Manzoni

The death of

Alessandro Manzoni in

1873 rekindled Verdi’s interest in the Requiem.

Manzoni was a beloved literary figure, and a leading

voice of the Catholic

spiritual revival that took place in 19th-century Italy.

On hearing of

Manzoni’s death, Verdi immediately wrote to the mayor of

Milan with an offer to

write a Requiem

for Manzoni, saying:

“It is a heartfelt impulse—or rather necessity—that

prompts me to honor as best

I can that Great One, whom I so much admired as a writer

and venerated as a

man.” As suggested by Mazzucato, Verdi had already

realized much of the music

for the Requiem

in his Libera me

setting of 1869. The Dies irae

section of the Libera

me was used to bind together the

many sections of the sequence, and much of the musical

material for the opening

Requiem aeternam

was ready-made in

the 1869 movement, as well. The remainder of the music

was completed by the end

of 1873. Verdi conducted the first performance of his Requiem at church of San Marco in Milan on

May 22, 1874, the first

anniversary of Manzoni’s death. The response to the

premiere was so enthusiastic

(at least three of the movements were encored) that the

Milanese demanded three

more performances, produced at the theater of La Scala.

Verdi took the work on

an international tour soon thereafter, and it was heard

throughout Italy, in

Paris, and in London.

The death of

Alessandro Manzoni in

1873 rekindled Verdi’s interest in the Requiem.

Manzoni was a beloved literary figure, and a leading

voice of the Catholic

spiritual revival that took place in 19th-century Italy.

On hearing of

Manzoni’s death, Verdi immediately wrote to the mayor of

Milan with an offer to

write a Requiem

for Manzoni, saying:

“It is a heartfelt impulse—or rather necessity—that

prompts me to honor as best

I can that Great One, whom I so much admired as a writer

and venerated as a

man.” As suggested by Mazzucato, Verdi had already

realized much of the music

for the Requiem

in his Libera me

setting of 1869. The Dies irae

section of the Libera

me was used to bind together the

many sections of the sequence, and much of the musical

material for the opening

Requiem aeternam

was ready-made in

the 1869 movement, as well. The remainder of the music

was completed by the end

of 1873. Verdi conducted the first performance of his Requiem at church of San Marco in Milan on

May 22, 1874, the first

anniversary of Manzoni’s death. The response to the

premiere was so enthusiastic

(at least three of the movements were encored) that the

Milanese demanded three

more performances, produced at the theater of La Scala.

Verdi took the work on

an international tour soon thereafter, and it was heard

throughout Italy, in

Paris, and in London.

There were a few critics who found

Verdi’s treatment of the Latin texts too “operatic” for

the solemn Mass, but he

composer’s wife Giuseppina answered them simply and

effectively: “Verdi must

write like Verdi—according to his way of feeling and

interpreting the text. The

religious spirit and the way in which it finds

expression must bear the imprint

of its time and the individuality of the author.” Just

what did the Requiem

mean to Verdi himself? The

genesis of the Requiem

was certainly

tied to what seems to have been genuine regard for

Rossini and Manzoni, and a

desire to memorialize them in a fitting way. However,

the work does not seem to

have been an expression of deep Catholic faith: Verdi

was notoriously private

about his inner life, but all indications point to the

probability that the Requiem’s

composer was an agnostic. (In

his classic biography of Verdi, Julian Budden points out

that two more openly

agnostic composers, Brahms and Vaughan Williams,

produced similarly profound

religious works.) Sacred composers in Italy at this

time—generally regarded as

second-raters who did not work in the more refined world

of opera—worked within

an established style that fit the conservative

liturgical purposes of the

Church. Verdi’s setting of this traditional text

transcends any traditional

boundaries.

Throughout his life, Verdi the

dramatist was attracted to strongly emotional

topics—selecting poems, novels,

and historical subjects that would transfer well to the

stage after they had

been adapted to the dramatic needs of a stage work and

made “singable” by a

librettist. In the Requiem Mass,

Verdi had a ready-made, dramatic, and eminently singable

text that covered to

entire range of human emotions, from terror, shame, and

sadness to hope and

exaltation. Verdi’s response to this text contains a

tremendous scope of

musical sentiment, ranging from the awful power of the Dies irae and the strict counterpoint of

the Sanctus, to the unabashedly emotional

outbursts of Recordare

and Ingemisco.

What You’ll Hear

Verdi clearly saw

the Requiem

texts with the eye of a great dramatist, and his settings

capture the Requiem’s

huge range of emotions. [Note

that this performance will be accompanied by a

projected translation.]

The Requiem opens quietly, with hushed

statements by the choir. Though

Verdi is not usually described as a writer of

counterpoint, the lush four-part

writing at Te

decet hymnus shows him

to be a master. At the Kyrie, Verdi

introduces the soloists, one by one. The end of the

movement builds towards the

first musical climax of the Requiem.

Verdi’s setting of the sequence

text Dies irae is

complex and

lengthy, spanning nearly half the duration of the Requiem. The movement opens with the first

statement of the words

“The day of wrath” together with full fortissimo

orchestra. Verdi may have been inspired, in part, by the

similarly massive and

theatrical setting of Dies irae by

Berlioz in his Requiem

Mass. Verdi’s Dies

irae returns throughout the second

section, as a reminder of the horrible Day of Judgment. The Tuba mirum

begins, appropriately, with trumpet calls echoing

between the orchestra and

four offstage trumpets, and the choir’s music continues

this fanfare-like

character. The stunning mezzo-soprano solo at Liber scriptus was written specifically

for Maria Waldmann, a fine

contralto, whose voice Verdi admired. This aria is

followed by a reprise of the

Dies irae. The

bleak prayer of the

vocal trio at Quid

sum miser is

followed by the distinctive dotted-note theme of Rex tremendae, and countermelodies in the

solo quartet. The Rex

tremendae ends with a passionate

setting of the words “Save me, O Fount of Pity.” The Recordare, Ingemisco, and

Confutatis are

more soloistic in

character: here Verdi gives his gift for melody free

reign. After a final

reprise of the Dies

irae, is the

closing scene of this religious drama’s first act. The

quartet and chorus

intone the passionate prayer of the Lacrymosa,

and the section closes with a hushed “Amen.”

The third movement, the Offertory,

is a showpiece for the quartet, containing moments of

what one writer has

called “undiluted opera.” The movement is held together

by two statements of

the music for quam

olim Abrahae—a

gentle reminder to the Lord of his promised redemption.

The Sanctus and Agnus Dei

texts are familiar parts of Ordinary of the Mass—those

movements that are sung

at every Catholic service—although the Agnus

Dei is changed slightly in the traditional Requiem to include a prayer for the dead.

In the Sanctus,

Verdi once again displays his

skill in countrapuntal writing: after an opening fanfare

and intonation, he

writess eight-part counterpoint for two opposed choirs.

The setting of Pleni

sunt coeli at the end provides

contrast with its more reserved style. The Agnus

Dei is a series of exchanges between the two

female singers and the chorus.

The choral writing here is beautiful in its simplicity,

and recalls many of

Verdi’s operatic choruses. The brief Lux

aeterna that follows contains quiet, almost

chantlike music for the three

lower voices of the vocal quartet.

Like the second movement, the Libera me is

lengthy and complex in

structure. Verdi made only slight revisions to the 1869

version of this

movement for the Manzoni Requiem. The

result is that much of the musical material he used for

earlier movements is

present here, as well. This makes it particularly

effective—it works like a

recapitulation of the most stirring themes and

sentiments. Verdi begins with a

quick recitation of the opening line of text and an

expanded treatment of the

imagery of catastrophe. After a final statement of the Dies irae, there is a passage of

breathtaking beauty: a soprano

melody on Requiem

aeternam that soars

to a high B-flat above unaccompanied chorus. For me,

this passage represents

the culmination of the entire Requiem—a

jewel of absolution and forgiveness set amidst the

destruction and fear of Judgment Day.

With the soprano’s

benediction still hanging in the air, the movement moves

towards its musical

climax: a massive choral fugue. The Requiem

does not end at this high level of volume and

excitement, however. Verdi brings

the Mass to a close with a quiet and intensely personal

appeal for deliverance.

Postscript:

For more

than a century, the Messa per Rossini

was known only as the first chapter in the story of

Verdi’s Requiem.

However, there is an epilogue

to this part of the story. In 1970, musicologist David

Rosen (who—I can’t

resist adding—was one of my teachers at UW-Madison!) was

in Milan, doing

research on Verdi, when he discovered a complete score

of the Messa per

Rossini, together with several

autograph scores of the individual movements. It had

long been supposed that

the Mass was lost, but it had it had been quietly

gathering dust in the Ricordi

vault for over a century. The Messa per

Rossini was finally given its world premiere in

1988—some 119 years late!

________