Madison Symphony

Orchestra Program Notes

March 15-16-17, 2024

98th Season /

Subscription Program 6

J.

Michael Allsen

This program opens with two works that are heard for the first time at these concerts. Jennifer Higdon’s Loco is a colorful and intensely rhythmic work...inspired by a commuter train. Cellist Steven Isserlis last appeared with the Madison Symphony Orchestra in 2007, performing the Schumann Cello Concerto. We welcome him back to Overture Hall to perform Kabalevky’s virtuosic Cello Concerto No. 2. Our third work has been be chosen by you, by way of our “audience choice” survey. After intermission, we turn to Dvořák’s fine “New World’ symphony—a musical response to the composer’s extended visit to the United States

Higdon, one of America’s leading

composers, wrote this work in 2004, for the Ravinia

Festival, among America’s most renowned summer festivals,

to be played by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Higdon, one of America’s leading

composers, wrote this work in 2004, for the Ravinia

Festival, among America’s most renowned summer festivals,

to be played by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Jennifer Higdon

Born: December

31, 1962, Brooklyn, New York.

Loco

•

Composed:

2004.

•

Premiere:

July 31, 2004, at the Ravinia Festival, by the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra.

•

Previous

MSO Performances: This is our first performance of

the work

•

Duration:

8:00.

Background

The Ravinia

Festival has a long history with train travel: Ravinia

Park was in fact founded by a commuter rail line! This

work was commissioned in honor of the Ravinia train, which

links the festival with downtown Chicago.

Jennifer

Higdon is among America’s most successful contemporary

composers. Born

in Brooklyn, she studied flute at Bowling Green State

University and composition at both the University of

Pennsylvania and at the Curtis Institute, where she taught

until 2021. In

2010, she won the Pulitzer Prize for her Violin Concerto,

one of many honors she has garnered in the past twenty

years. In just the last few years, her first opera, Cold

Mountain, won the prestigious International Opera

Award for Best World Premiere in 2016—the first American

opera to do so in the award’s history. Within the past two

years, Higdon has had successful premieres of her Double

Percussion Concerto with the Houston Symphony

Orchestra, the Cold

Mountain Suite with the Delaware Symphony, and The Absence, Remember,

a choral work commissioned by several choruses. She is among

America’s most frequently-programmed composers, and her blue cathedral is

among the most often-played pieces of contemporary music,

receiving well over 600 performances since its premiere in

2000 (including a performance by the MSO in 2013).

As electric

railways and trolley lines began to spread across American

cities at the turn of the 20th century, it was relatively

common for the operators of these new lines to open

amusement parks and other attractions that could be easily

reached by rail. This was a public service, providing

leisure activities to people from all levels of

society...but it was also good business, increasing

ridership on weekends, holidays and during the summer. In 1904, the

newly-established Chicago and Milwaukee Electric Railroad

opened Ravinia Park in Chicago’s northern suburb of

Highland Park. Music was a centerpiece of the activities

at Ravinia from the beginning, with opera performances and

concerts by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. (Ravinia

became the CSO’s official summer residence in 1936.) Today, the

Ravinia Festival bills itself as “the oldest and most

programmatically diverse music festival in North America.” And the

train—which is free to ticket-holders—is still the best

way to get there from downtown Chicago! Loco was

commissioned by the Ravinia Festival to celebrate the

Ravinia Train.

What You’ll Hear

A brisk

“curtain-raiser,” Loco

is an entertaining and rhythmically intense piece that

subtly refers to the sound and motion of a rail journey.

In

describing the work

Higdon noted: “Loco

celebrates the Centennial season of Ravinia, and the train

that accompanies the orchestra. When thinking about what

kind of piece to write, I saw in my imagination a

locomotive. And in a truly ironic move for a composer, my

brain subtracted the word ‘motive,’ leaving ‘loco,’ which

means crazy. Being a composer, this appealed to me, so

this piece is about locomotion as crazy movement!” This

intense eight-minute work evokes the train in machine-like

writing across sections and in small details, like the

“Doppler effect” train horns from the trombones.

This concerto is generally considered to

be among Kabalevsky’s finest orchestral works: an

emotional showpiece for the cello, with a beauty that

sometimes rough-edged.

This concerto is generally considered to

be among Kabalevsky’s finest orchestral works: an

emotional showpiece for the cello, with a beauty that

sometimes rough-edged.

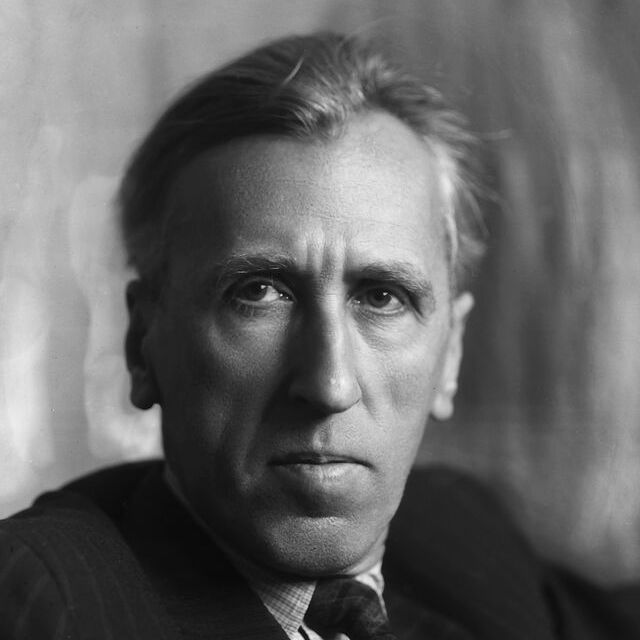

Dmitri Kabalevsky

Born:

December 30, 1904, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Died:

February 14, 1987, Moscow, Russia.

Concerto No. 2 in

E minor for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 77

•

Composed:

1964

.

• Premiere:

Cellist Daniil Shafran, to whom the score is dedicated,

played the first performance in Leningrad (St. Petersburg)

in 1965, under the direction of the composer.

•

Previous

MSO

performance: This is our first performance of the

work.

•

Duration:

29:00.

Background

Kabalevsky

wrote this work for the Soviet cellist Daniil Shafran.

Dmitri

Kabalevsky was one of the leading composers of the Soviet

Union, and worked comfortably for his entire career in the

restrictive atmosphere of Soviet music. Kabalevsky’s

musical style was never even remotely “modernist” and

suited perfectly the ideal that music should be uplifting

and in service of the people. A loyal member

of the Communist Party, he enthusiastically supported

Soviet musical policies, and held several important

political positions and editorships. Interested in

the cause of education, Kabalevsky also helped to

formulate the Soviet music education system, writing

dozens of works for children’s choir, and later in his

career, influential books on teaching music.

Kabalevsky

wrote his first cello concerto in 1949, as part of a trio

of works—with his third piano concerto and violin

concerto—that the education-minded composer had created

with accessibility to younger players in mind. (I’ll note

that all three of these works have been performed over the

years by young soloists at MSO youth programs.) The second

concerto was an entirely different sort of piece, written

for a specific virtuoso, Daniil Shafran (1923-1997).

Shafran was among the most prominent soloists in the

Soviet Union, and was known as a peer and sometime

competitor to his contemporary, Mstislav Rostropovich.

Kabalevsky was particularly pleased by a 1954 recording of

the Cello Concerto

No. 1 by Shafran. Ten years later, he dedicated the

Cello Concerto No.

2 to the cellist, and Shafran played its premiere

and first recording under the direction of Kabalevsky.

What You’ll Hear

The concerto is

in three movements, played without pauses:

• A lengthy

opening movement with slow opening and closing sections

surrounding a wild middle. It ends with a solo cadenza.

• A fast-paced

scherzo, also ending with a cadenza.

• A finale that

explores themes from previous movements before ending

quietly.

The first

movement opens mysteriously (Molto sostenuto):

a pizzicato

melody from the soloist above long-held bass tones. This melody is

played twice more, by flutes and then by violins, with a

passionate overlay from the soloist. A fourth statement is

interrupted by a sudden change in tempo (Allegro molto e

energico) and a furious and angular melody from the

cello. The

tempo eventually slows and the cello lays out a melancholy

melody. The

movement ends with a large solo cadenza, which leads into

the second movement (Presto

marcato). This

begins with aggressive music led by a solo alto saxophone. The cello takes

up this idea, and plays fierce perpetual motion above the

shifting rhythms of the orchestra. The forward

motion is halted momentarily by a strident brass

statement, but the cello soon launches into another

fast-paced countermelody. Once again, Kabalevsky uses an

extended solo cadenza as a bridge into the next movement.

The closing movement begins quietly (Andante con moto)

with a lyrical cello line. As the tempo quickens (Allegro),

Kabalevsky refers to ideas from the previous movements,

before the piece ends calmly and quietly.

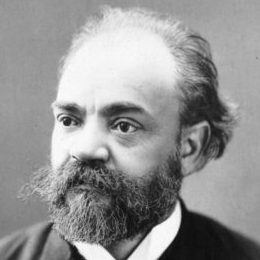

Dvořák’s

Symphony No. 9, his

last and most enduringly popular symphony, was written

during an enjoyable

three-year stay in America in the 1890s.

Dvořák’s

Symphony No. 9, his

last and most enduringly popular symphony, was written

during an enjoyable

three-year stay in America in the 1890s.

Antonín Dvořák

Born: September 8,

1841, Nelahozeves,

Czech Republic.

Died: May 1, 1904,

Prague, Czech

Republic.

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op.95 (From the New World)

•

Composed: During the winter

and spring of

1892-93 in New York City.

•

Premiere:

December 16, 1893, by the New York

Philharmonic, Anton Seidl conducting.

•

Previous MSO Performance:

1930, 1935, 1975, 1994, 2005, 2014,

and 2017.

•

Duration: 40:00.

The symphony is partly a response

to his time in the New World.” Dvořák

was

fascinated by American culture and music, and there are

few a distinctly

American elements in this work.

Background

In 1892,

Jeannette Thurber made Dvořák

an

offer he couldn’t

refuse. Thurber, the

wife of a wealthy New York businessman, had a dream of

raising the standards of

American art music to equal those of Europe.

She had founded the National

Conservatory of Music in 1885, and recruited some of the

finest teachers in the

world to serve on its faculty.

At

this time, Dvořák’s

reputation among

American

musicians was

surpassed only by that of Brahms, and Thurber resolved

to hire him as the

director of the Conservatory.

Dvořák

was lukewarm at first, but the

terms she offered were very generous:

a

two-year contract, with very light teaching duties and

four months’

paid leave each year. The

annual salary, $15,000, was

about 25 times what Dvořák

was

making as an instructor at the Prague Conservatory, and

in the end he accepted,

eventually spending about three years in this country.

Dvořák

enjoyed this American sojourn.

American audiences adored his

music, and he blended comfortably into New York society.

He spent two summers

in the small town of Spillville, Iowa, where he felt at

home in a large

Bohemian community. He

had

several promising composition students at the

Conservatory, and agreed

heartily with Thurber’s

ideal that American composers should foster their own

distinctive style of

composition. He

wrote that:

“My

own

duty as a teacher is not so much to interpret Beethoven,

Wagner, and other

masters of the past, but to give what encouragement I

can to the young

musicians of America... this nation has already

surpassed so many others in

marvelous inventions and feats of engineering and

commerce, and it has made an

honorable place for itself in literature—so it must

assert itself in the other

arts, and especially in the art of music.”

The “New

World” symphony is the most famous of the works Dvořák

composed while in America.

According to Thurber, the symphony

was written at her suggestion—she felt that Dvorák

should write a symphony

“…embodying his experiences and feelings in America.”

It was an immediate hit with

audiences in both America and Europe.

The

new symphony closely matched the style of his other late

symphonies, a style

based on the German symphonic style of his mentor,

Brahms, and with occasional

hints of Bohemian folk style.

There

are a few “Americanisms” in the Symphony

No.9, however. As

a

strongly nationalistic Bohemian, Dvorák had always

brought the spirit of his

homeland into his works by bringing in folk tunes, and

by more generally

imitating the sound of Bohemian music.

According

to his own account of the work’s

composition, Dvořák attempted

to

do the same with regards to American music in the Symphony No.9, and he was particularly

interested in two forms of

music that had their origins on

this side of the Atlantic:

Native American music and African

American spirituals. Dvořák

frequently quizzed one his students

at the National Conservatory, a talented young Black

singer named Harry T. Burleigh,

about spirituals, and he dutifully transcribed every

spiritual tune Burleigh

knew. His contact

with Native American music was a little more

tenuous—most of what Dvořák

knew came from rather dubious

published transcriptions.

(The

only time he ever heard an “authentic”

American

Indian performance was when he went to Buffalo Bill’s

Wild West Show!) While

he did not use any true

American melodies in the symphony, Dvořák

immersed

himself in American music and culture, and wrote musical

themes from this

inspiration. At

its heart,

however, the Symphony

No.9 is a work

“From the New

World” by an Old World

composer. Dvořák

was not trying to create an

“American Style”—he firmly believed that that was a job

for American composers.

The symphony is in four movements;

• An extended movement in sonata

form with a slow introduction. Its bold

main theme, introduced by the horns will appear as a

musical motto in all four

movements.

• A slow movement, whose lovely

main theme evokes the sound of a

spiritual.

• A lively scherzo.

• A fiery finale in sonata form,

which recalls themese from earlier

movement in its closing section.

What You’ll

Hear

The

opening movement begins with an Adagio

introduction, which gradually speeds and resolves into

the main body of the

movement (Allegro

molto). Dvořák

immediately announces the main

theme, a distinctive motto that will appear, in one form

or another, in every

movement of the symphony.

This

bold E minor theme is first played by the horns, and

then expanded by the

strings. He introduces

two contrasting melodies, a dancelike minor-key melody

in, introduced by the

oboe, and somewhat brighter theme heard in the solo

flute. This sonata-form

movement features

a lengthy development section, which focuses on the

motto theme. After

a conventional recapitulation,

there

is a long coda, which

again explores the motto theme.

There are

a few programmatic elements in the Symphony

No. 9. According to Dvořák, the second and third

movements were inspired by

Longfellow’s

Song of Hiawatha;

in the Largo it is Hiawatha’s

“Funeral in the Forest.” This

movement is set in a broad

three-part form. It

opens

with a solemn brass chorale, which leads into the

movement’s main theme, a

long Romantic

melody played by the English horn.

(This

melody became popular as nostalgic song called Goin’

Home—so popular,

in fact, that it was widely assumed that it was a

traditional spiritual that Dvořák

had quoted!)

The contrasting middle section

features a more pensive melody heard first in the flute.

The movement ends with a return of

the English horn melody.

Dvořák

again referred to Hiawatha in the

Scherzo (Molto

vivace), stating that this

movement was supposed to depict “…a feast in the wood,

where the Indians

dance.” The first

section features two main themes, an offbeat melody

introduced by solo

woodwinds and a more lyrical melody played by the

woodwinds as a section.

Echoes of the motto theme lead gradually into a central

trio. The trio section is

certain

dancelike, but its waltz-style themes seem to have a lot

more to do with a

Viennese ballroom than an American Indian dance.

The

opening section returns, and Dvořák

closes

the movement with more reminiscences of the motto theme.

The finale

(Allegro con fuoco)

begins with a few

stormy introductory measures, and then Dvorák brings in

the main theme in the

brass. After this

powerful theme, there is a more lyrical melody in the

solo clarinet. Dvořák

set the finale in sonata form, but

he used the lengthy development not only to work with

this movement’s

themes, but also to develop music

from previous movements. In

particular,

we hear versions of the motto and a faster reading of

the Largo’s

main theme. After

recapitulating the fourth

movement’s main themes,

Dvořák launches into

a huge coda, which again brings back material from

previous movements.

________