Madison Symphony

Orchestra Program Notes

January 19-20-21, 2024

98th Season / Subscription Program 5

J. Michael Allsen

To open this

program, we welcome back pianist Joyce Yang. Ms. Yang

previously appeared with Madison Symphony Orchestra in

2019, with a memorable performance of Prokofiev’s third

piano concerto. At these concerts she performs Mozart’s

Piano Concerto No.

24, among his most tense and serious works for

solo piano. We

then turn to the vast Symphony No. 5

by Gustav Mahler, a work the composer identified as a

new phase in his development.

This

uncharacteristically serious work was one of three piano

concertos Mozart composed at the same time he was

working on his opera The Marriage of

Figaro.

This

uncharacteristically serious work was one of three piano

concertos Mozart composed at the same time he was

working on his opera The Marriage of

Figaro.

Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart

Born:

January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria.

Died:

December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria.

Concerto No. 24 in

C minor for Piano and Orchestra, K. 491

•

Composed:

Completed March 24, 1786.

• Premiere: The

composer probably played and conducted the first

performance in a concert at Vienna’s Burgtheatre on April

7, 1786.

•

Previous

MSO Performance: 1984, with pianist Charles Rosen.

•

Duration:

23:00.

Background

Fifteen of

Mozart’s twenty-seven piano concertos, including No. 24, were

written for his public concerts in Vienna. These concerts

were a major factor in establishing himself in the

imperial capital.

Mozart’s

reputation and success in his early years in Vienna came

largely through his private recitals, and public

“subscription” performances of his own works. Viennese

audiences demanded new concertos at every concert, and

Mozart responded with an amazing series of fifteen

concertos written during his first five years in Vienna.

The winter of 1785-86 was a particularly busy time: his

main concern was the opera The Marriage of Figaro, which would premiere

in Vienna in May 1786, but he was obliged to take time in

February to dash off a one-act Singspiel, The Impresario,

for a commission by the Emperor. He also managed

to find time to complete three piano concertos: No. 22 in

December, No. 23

on March 2, and No.

24 just three weeks later on March 24. The bulk of

Viennese public concerts occurred during the Christmas

season and Lent, and No. 22 was played on December 26. Mozart had at

least three subscription concerts that spring, and the

other two concertos were probably performed at these. One

innovation he introduced in these three concertos was a

pair of clarinets, substituting for the usual oboes in the

first two, and as part of a relatively large scoring in No. 24. He was inspired

by his friendship with the clarinetist Anton Stadler, and

he used clarinets prominently in Figaro as well.

What You’ll Hear

This work is in

three movements:

• A broad opening

movement set in sonata form.

• A Larghetto, with a

lyrical main theme and two contrasting episodes.

• A set of

variations on a march-style theme.

The Piano Concerto No. 24

is the largest of the three concertos, and certainly the

most serious in tone: it is one of only two piano

concertos he cast in a minor key. The opening Allegro begins

with a stern orchestral exposition that presents a rich

array of material for the movement, alternating between a

threatening main theme (sounding very much like the

introduction to a tragic opera) and flowing woodwind

passages. When the piano enters, it is with an entirely

new idea, lyrical and melancholy, before the orchestra

announces the main theme and the solo part begins a

decorated version of the exposition. The extensive

development section begins with a return to the piano’s

initial music and then works primarily with the main

theme. Following an abbreviated recapitulation, Mozart

leaves space for a solo cadenza, before ending in a stormy

coda.

The Larghetto is a

complete change in mood, beginning with a main idea from

the piano in luminous E-flat Major. This idea alternates

with a pair of contrasting episodes, both of them led by

the woodwinds: the first pensive and the second more

pastoral. The final statement of the main theme is

interrupted briefly for a short cadenza. The closing

movement (Allegretto)

presents a set of six variations on a marchlike theme

introduced by the orchestra.

After three increasingly intense variations, the

fourth variation is suddenly in a pastoral major key, led

by the woodwinds. A more agitated variation by the solo

piano follows, and the sixth variation transforms the

theme into much happier music in C Major. Mozart returns

firmly to C minor at the end, setting up a final solo

cadenza. This leads directly into the coda, based upon an

entirely new idea set in 6/8.

In describing his fifth symphony, Mahler

referred to it as a work in a “completely new style.” This

colossal work breaks with his earlier symphonies: there is

no program and no reliance on vocal music, but instead a

starker and more intellectual approach.

In describing his fifth symphony, Mahler

referred to it as a work in a “completely new style.” This

colossal work breaks with his earlier symphonies: there is

no program and no reliance on vocal music, but instead a

starker and more intellectual approach.

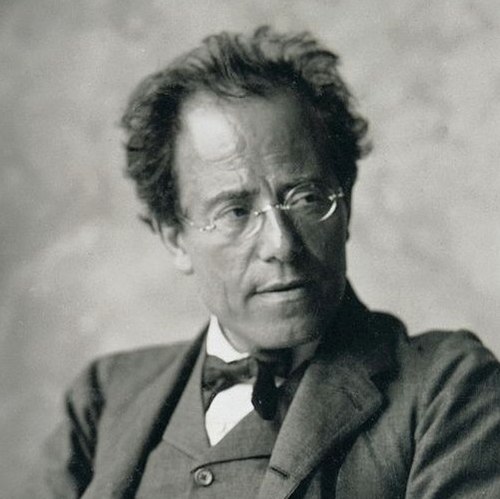

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7,

1860, Kalischte, Bohemia.

Died: May 18,

1911, Vienna, Austria.

Symphony No. 5 in

C-sharp minor

• Composed:

1901-1902. He continued to revise the score over the next

several years.

•

Premiere:

October 18, 1904 in Cologne, conducted by the composer.

•

Previous

MSO Performances: 1982 and 1998.

•

Duration:

69:00.

Background

This work was

composed at the time of Mahler’s marriage to Alma

Schindler and other momentous changes in his career. Due

to his conducting schedule, the time and solitude he

needed to compose was available only in during summer

holidays. The

Symphony No. 5

was completed in the summers of 1901 and 1902.

1901 was one

of the most significant years of Mahler’s life. He acquired

property at Mayernigg, near Lake Wörther in southern

Austria: the beloved summer retreat where most of his late

works were composed.

There were professional changes as well: early that

year, health problems, apparently caused by overwork,

forced him to step down as conductor of the Vienna

Philharmonic. (From

all accounts, the musicians of this democratically-run

orchestra had long chafed under Mahler’s authoritarian

style. During his absence, they quickly elected another

conductor, even before Mahler had a chance to resign

officially!) However,

the most important event of 1901 was meeting Alma

Schindler at a dinner party.

Mahler was instantly attracted to this brilliant

and beautiful 20-year-old, who was a composer in her own

right. For

her part, Alma Schindler was just a bit awed by the

conductor and composer, who was twice her age. A romance

blossomed quickly, and they were married on March 2, 1902. Marriage was a

very good thing for Gustav, though Alma’s musical career

was cut short at his insistence: she was to be his partner

in most things, but there was apparently room for only one

composer in the family.

Alma was able to take care of the day-to-day

details of housekeeping and business that he found so

irritating, leaving him freer to compose.

Composition

was almost exclusively limited to summer holidays, and the

time Mahler spent at Mayernigg was jealously guarded. According to

Alma’s diary, he maintained a strict regime. He rose at dawn

and tromped up to his “composition cottage” in the woods—a

small shed that contained little besides a desk and a

piano. His

breakfast was brought up by a maid, who according to Alma,

was terrified of Mahler, and would leave the tray and run. He would work in

solitude all morning, and after lunch would hike or row

with Alma. Even

during the afternoons and evenings, he would be working on

compositional problems, and would suddenly break away from

guests or other activities to work for hours at a time. The Symphony No. 5

was composed during two of these holidays, in 1901 and

1902.

The "composition cottage" at Mayernigg

This work, which Mahler originally

nicknamed the “giant symphony,” was essentially complete

in 1902, but was to be revised extensively several times. After a

preliminary sight-reading in 1904, he deleted many of the

percussion parts that were prominent in the first version. (Alma writes in

her diary of “sobbing aloud” when she heard the percussion

drowning out the rest of the orchestra.) Though the

premiere went well later that year, he made significant

changes before conducting the work in Amsterdam in 1906,

and revised it yet again for a performance in 1908. It was not until

shortly before his death—and after completing four more

symphonies—that Mahler wrote to a friend: “I have finished

the Fifth. I

actually had to reorchestrate it completely. I don’t

understand how I could have gone so completely astray—just

like a beginner. Evidently

the routines I had established with the first four

symphonies were entirely inadequate for this one—for a

completely new style demands a new technique.”

This work, which Mahler originally

nicknamed the “giant symphony,” was essentially complete

in 1902, but was to be revised extensively several times. After a

preliminary sight-reading in 1904, he deleted many of the

percussion parts that were prominent in the first version. (Alma writes in

her diary of “sobbing aloud” when she heard the percussion

drowning out the rest of the orchestra.) Though the

premiere went well later that year, he made significant

changes before conducting the work in Amsterdam in 1906,

and revised it yet again for a performance in 1908. It was not until

shortly before his death—and after completing four more

symphonies—that Mahler wrote to a friend: “I have finished

the Fifth. I

actually had to reorchestrate it completely. I don’t

understand how I could have gone so completely astray—just

like a beginner. Evidently

the routines I had established with the first four

symphonies were entirely inadequate for this one—for a

completely new style demands a new technique.”

This

“completely new style” represents a break with what he had

done in the first four symphonies. Despite their variety

in style, all of these were programmatic: having a clear

storyline or meaning. All of them are also based in some

way upon Mahler’s musical settings of the folk-style poems

from Des Knaben

Wunderhorn (The

Boy’s Magic Horn).

In the Symphony

No.5, Mahler rejects the idea of an extramusical

program, and breaks with the use of vocal music and text

that had been so much a part of the second, third, and

fourth symphonies. The

symphony also makes a musical break with his previous

works. It was

during this period that Mahler began to study the works of

J. S. Bach. (The

only printed music in Mahler’s “composition cottage” at

Mayernigg was a prized set of the Bach Complete Works.) A newer, more

intellectual contrapuntal style is heard in this symphony.

What You’ll Hear

The symphony is

laid out in five large movements:

• A stern

“funeral march,” beginning with a trumpet fanfare. Mahler

intended this to serve as an extended introduction to the

second movement.

• A

ferocious second movement in a loose sonata form that

builds towards a titanic brass chorale.

• An enormous

scherzo organized around a series of Austrian-style dance

tunes, and a darker contrasting trio.

• A serene Adagietto, scored

for strings and harp. This leads directly into the finale.

• The Rondo-Finale,

which again uses a dance tune as a main theme, in a

movement that features dense contrapuntal writing,

The Symphony No.5 is

set in five movements, which Mahler organizes into three

parts: the funeral march and second movement constitute

Part I, Part II consists of the gargantuan Scherzo, and Part

III includes the Adagietto

and Rondo-Finale. The symphony

begins with a solemn fanfare from a solo trumpet—this

rhythm pervades much of the movement’s music. Mahler

titles the movement Trauermusik (funeral music) and gives the

direction In

gemessen Schritt, streng, wie ein Konduit (In

measured step, stern, as in a funeral procession). The

opening fanfare leads into a somber march for brass, and a

sad string melody. The

trumpet fanfare appears again, and there is an almost

violent middle passage that breaks the solemn march and

moves towards an angry climax. Once again, the

trumpet interjects, and there is a long concluding passage

that returns to the defeated tread of the opening march. The movement

dies away quietly and gradually.

Mahler

considered the funeral march to be an introduction to the

second movement, marked Stürmische bewegt,

mit grösster Vehemenz (Stormily agitated, with

greatest vehemence), which begins without a pause. The movement,

set in a greatly expanded sonata form, begins with a

furious figure in the basses that the brasses answer with

equal rage. The mood breaks suddenly, and the cellos play

a sad tune that recalls the march of the first movement. The development

begins with a recitative-style line for the cellos that

Mahler marks Klagend

(“grieving”). This

section builds gradually through restatements and

recombinations of his themes, over a vast stretch of

musical time, before culminating in a titanic brass

chorale—Mahler marks this moment in the score Höhepunkt

(high-point or climax—as if we could fail to notice!) When

the opening theme returns, it is almost an afterthought to

this moment—it builds towards a second peak, but then

subsides to fade away to nothing. Mahler specifies

a long break after the close of this movement.

The title Scherzo (Italian

for “joke”) usually implies a light, sometimes humorous,

fast-paced movement. While there is certainly humor to be

found in this movement, it is no lightweight—at over 800

measures, it is the longest section of the symphony. Mahler wrote to

Alma while he was rehearsing for the premiere, describing

it as

“the devil of a movement. I see it is in

for a lot of trouble.

Conductors for the next fifty years will all take

it too fast, and make nonsense of it; and the public—what

are they to make of this chaos of which new worlds are

forever being engendered, only to crumble in into ruin the

moment after. What are they to say to this primeval music,

this foaming, roaring, raging sea of flashing breakers? Oh that I might

give my symphony its first performance fifty years after

my death!”

The main

theme is stated by all four horns, and the opening panel

is series of several dance melodies—mostly in the

rough-edged character of the Austrian country laendler,

but occasionally lapsing into a citified waltz. The lengthy trio

uses a more reflective idea stated by solo horn, which is

then developed. Just

when everything seems to be dwindling to a close, the

strings begin an upbeat Laendler tune and sweep the rest

of the orchestra towards a climax (listen for a prominent

woodblock solo). The

horns enter again and there is a varied restatement of the

opening material, with dense contrapuntal elaboration. The coda turns

briefly to the darker mood of the trio, before ending

abruptly with a final horn fanfare: a formal trick Mahler

certainly learned from the Scherzo movements

of his hero, Beethoven.

Part III of

the symphony begins with the dreamy Adagietto. This

movement, scored simply for strings and harp, is dwarfed

by the movements that surround it, and shows Mahler’s more

introspective side. It

is based upon two long melodies sung by strings, and

mounts to a subdued peak and then fades away. As in Part I,

there is no break between this movement and the next.

The Rondo-Finale

begins with a wonderful passage in which sustained tones

from the horn are answered by solo woodwinds. This leads

to a Austrian country-band passage that serves as the

refrain in this movement.

The refrain closes as the cellos begin vigorously

laying out an agitated line that becomes the subject of an

extended fugue. The

refrain returns again, and another contrapuntal episode

begins, eventually moving towards a new version of the Adagietto’s main

melody. This

becomes a theme for a series of loosely-structured

variations, as the movement works inexorably towards a Höhepunkt—again,

a triumphal brass chorale, now decorated by the strings

and woodwinds playing the fugue subject. There is little

that remains unsaid at this point, and the movement comes

quickly to a close.

________

program notes ©2023 by J. Michael

Allsen