Madison

Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

December 1-2-3, 2023

98th Season / Subscription Program 4

J. Michael Allsen

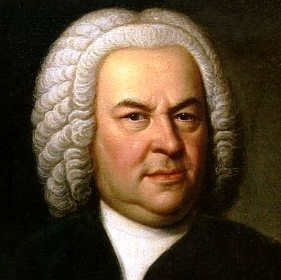

The Mass in

B minor, Johann Sebastian

Bach’s most monumental

sacred work, was

completed in the

last year of his life, but it is actually an immense

patchwork of movements

assembled over the course of some thirty years. The

choruses heard on this

program date from the 1730s, when Bach was

becoming dissatisfied with

the limited resources available to him as Kantor of

Lewipzig Thomaskirche. He

made several attempts during this period to better his

situation. In 1733, he

sent a “Missa,” a setting of the Kyrie

and Gloria of

the mass, to the

opulent Dresden court of the Elector of Saxony. Bach hoped

that this sample of

his work, which he referred to as a “trifling product of

that science which I

have attained in Musique,” would lead to a position in

Dresden. In the end, only

a more modest request was granted: that the Elector name

him court composer, a

position of little more than honorary significance. The

chorus Gloria in

excelsis Deo is joyous, with

complex vocal lines intertwining with a trumpet ritornello. At Et in terra

pax hominibus, the mood becomes more pensive, with a

pair of musical ideas

combined in ever more complicated counterpoint.

The Mass in

B minor, Johann Sebastian

Bach’s most monumental

sacred work, was

completed in the

last year of his life, but it is actually an immense

patchwork of movements

assembled over the course of some thirty years. The

choruses heard on this

program date from the 1730s, when Bach was

becoming dissatisfied with

the limited resources available to him as Kantor of

Lewipzig Thomaskirche. He

made several attempts during this period to better his

situation. In 1733, he

sent a “Missa,” a setting of the Kyrie

and Gloria of

the mass, to the

opulent Dresden court of the Elector of Saxony. Bach hoped

that this sample of

his work, which he referred to as a “trifling product of

that science which I

have attained in Musique,” would lead to a position in

Dresden. In the end, only

a more modest request was granted: that the Elector name

him court composer, a

position of little more than honorary significance. The

chorus Gloria in

excelsis Deo is joyous, with

complex vocal lines intertwining with a trumpet ritornello. At Et in terra

pax hominibus, the mood becomes more pensive, with a

pair of musical ideas

combined in ever more complicated counterpoint.

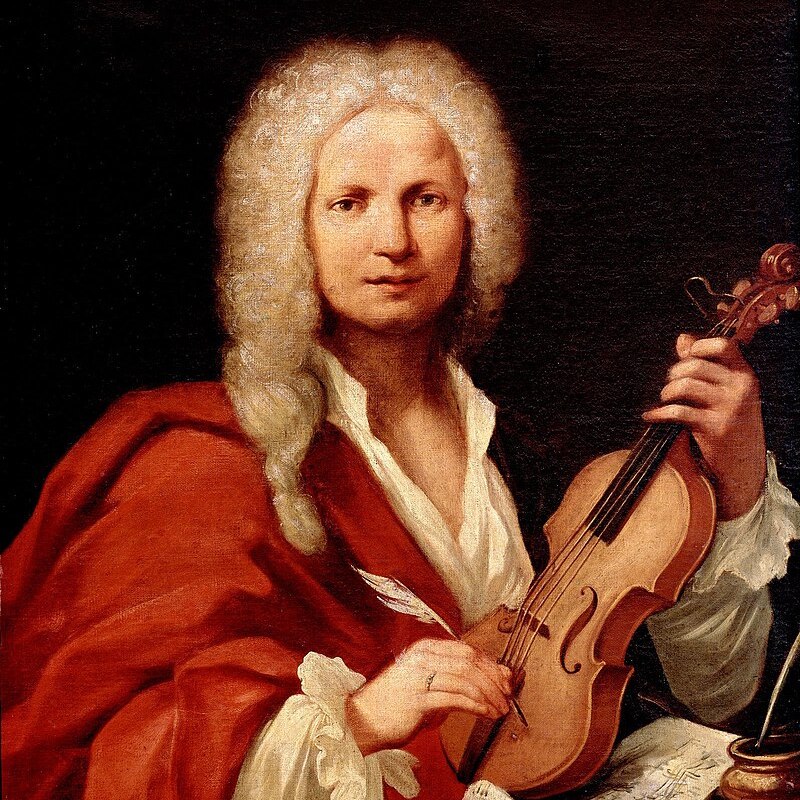

Antonio

Vivaldi was

the most prominent and influential Italian composer of

the late Baroque. He

composed in nearly every genre—some 40 of his operas,

dozens of his sacred

works, and nearly 100 of his chamber works survive—but

it was his 500 concertos

that had the broadest influence. These concertos were

widely circulated and

emulated in Vivaldi’s day, and it was he who established

many of the standard

operating procedures followed by his contemporaries

Bach, Handel, and Telemann

in their concerto writing. Most of his works were

written for use at the

Ospedale della Pietà, the girl’s orphanage in Venice

where he spent much of his

early career. The orchestra he directed at the Pietà

must have been a fine one,

and the concertos were written to feature either Vivaldi

himself (a leading

Italian violinist), other professional musicians

associated with the school, or

the students themselves. His Piccolo Concerto

was probably

written originally for the flautino

(sopranino recorder), but it is most frequently heard

today on the piccolo.

Though we are unsure as who played the solo part

originally, Vivaldi was

associated with at least two fine German recorder

players who taught at the

Pietà, Ignaz Sieber and Ludwig Erdman, and met many

other players who toured

through Venice in the earlyh century. The concerto is in

the standard Baroque

form, with three contrasting movements. The opening Allegro features the usual Baroque

alternation of tutti sections

with more virtuosic writing for the soloist. The Largo is set in the sensuous Siciliano

rhythm. The closing movement, Allegro

molto, has a more sprightly character, and again

leaves plenty of room for

flashy playing by the soloist.

Antonio

Vivaldi was

the most prominent and influential Italian composer of

the late Baroque. He

composed in nearly every genre—some 40 of his operas,

dozens of his sacred

works, and nearly 100 of his chamber works survive—but

it was his 500 concertos

that had the broadest influence. These concertos were

widely circulated and

emulated in Vivaldi’s day, and it was he who established

many of the standard

operating procedures followed by his contemporaries

Bach, Handel, and Telemann

in their concerto writing. Most of his works were

written for use at the

Ospedale della Pietà, the girl’s orphanage in Venice

where he spent much of his

early career. The orchestra he directed at the Pietà

must have been a fine one,

and the concertos were written to feature either Vivaldi

himself (a leading

Italian violinist), other professional musicians

associated with the school, or

the students themselves. His Piccolo Concerto

was probably

written originally for the flautino

(sopranino recorder), but it is most frequently heard

today on the piccolo.

Though we are unsure as who played the solo part

originally, Vivaldi was

associated with at least two fine German recorder

players who taught at the

Pietà, Ignaz Sieber and Ludwig Erdman, and met many

other players who toured

through Venice in the earlyh century. The concerto is in

the standard Baroque

form, with three contrasting movements. The opening Allegro features the usual Baroque

alternation of tutti sections

with more virtuosic writing for the soloist. The Largo is set in the sensuous Siciliano

rhythm. The closing movement, Allegro

molto, has a more sprightly character, and again

leaves plenty of room for

flashy playing by the soloist.

The Belgian organist and composer César Franck would eventually be appointed

organ professor of the

Paris Conservatory in 1872, but he spent nearly all of his

working as a church

musician. He settled permanently in Paris in 1845,

securing a series of

increasingly prestigious organ jobs that led eventually to

his appointment as

organist at the basilica of Ste. Clothilde in 1858, a

position he held until

his death in 1890. His beloved Panis Angelicus

was composed in 1872

for the choir of Ste. Clothilde. It is part of a

13th-century Latin communion

hymn written by St. Thomas Aquinas. Franck’s setting shows

his gift for

presenting a straightforward and lyrical melody above

skillful and complex

counterpoint.

The Belgian organist and composer César Franck would eventually be appointed

organ professor of the

Paris Conservatory in 1872, but he spent nearly all of his

working as a church

musician. He settled permanently in Paris in 1845,

securing a series of

increasingly prestigious organ jobs that led eventually to

his appointment as

organist at the basilica of Ste. Clothilde in 1858, a

position he held until

his death in 1890. His beloved Panis Angelicus

was composed in 1872

for the choir of Ste. Clothilde. It is part of a

13th-century Latin communion

hymn written by St. Thomas Aquinas. Franck’s setting shows

his gift for

presenting a straightforward and lyrical melody above

skillful and complex

counterpoint.

Francis Poulenc, known most often as a musical

humorist, was also a deeply

religious man. He rediscovered his Catholic faith while

in his late 30s, and

many of his choral works, beginning with the Mass in G Major of 1937 were settings of

Latin religious texts. Poulenc's

religious vision reflected his own joie

de vivre, and his religious music is never pompous

or conventional. The Gloria,

one of Poulenc’s last completed works, was written in

1959-60, for a commission

from the Koussevitsky Music Foundation, and first

performed in Boston in 1961. Poulenc

divides the traditional text of the Gloria, part of the

Latin Mass, into six

sections, three of them performed here. The music

reflects both a deep

understanding of the text and Poulenc’s own joyful

spirituality. The opening

movement begins with delicate orchestral textures, but

soon gives way to exuberant

calls of Gloria—a

word returns

constantly throughout this movement. Nowhere in the

Gloria is Poulenc’s sense

of humor more evident than in the witty Laudamus

te. Only in the central section (Gratias

agimus tibi gloriam tuam), does the mood become

sober, but even here, there

is a sense of tongue-in-cheek dignity that shows that

Poulenc’s praises are

offered with a cheerful spirit. The final movement, Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, beginning

with an intonation by men’s

voices of the opening prayer, returns to the exalted

mood of the first

movement. Poulenc expands on this text, an invocation of

the the Trinity, in an

elaborate development section, but the movement closes

with hushed Amens

from the chorus and soprano. [MSO historical

note: In 1963, just two

years after its premiere, The Madison Civic Chorus and

Madison Civic

Symphony—predecessors of today’s chorus and orchestra,

and then under the direction

of Roland Johnson—gave the first Midwestern

performance of this now-standard

work. - M.A.]

Francis Poulenc, known most often as a musical

humorist, was also a deeply

religious man. He rediscovered his Catholic faith while

in his late 30s, and

many of his choral works, beginning with the Mass in G Major of 1937 were settings of

Latin religious texts. Poulenc's

religious vision reflected his own joie

de vivre, and his religious music is never pompous

or conventional. The Gloria,

one of Poulenc’s last completed works, was written in

1959-60, for a commission

from the Koussevitsky Music Foundation, and first

performed in Boston in 1961. Poulenc

divides the traditional text of the Gloria, part of the

Latin Mass, into six

sections, three of them performed here. The music

reflects both a deep

understanding of the text and Poulenc’s own joyful

spirituality. The opening

movement begins with delicate orchestral textures, but

soon gives way to exuberant

calls of Gloria—a

word returns

constantly throughout this movement. Nowhere in the

Gloria is Poulenc’s sense

of humor more evident than in the witty Laudamus

te. Only in the central section (Gratias

agimus tibi gloriam tuam), does the mood become

sober, but even here, there

is a sense of tongue-in-cheek dignity that shows that

Poulenc’s praises are

offered with a cheerful spirit. The final movement, Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, beginning

with an intonation by men’s

voices of the opening prayer, returns to the exalted

mood of the first

movement. Poulenc expands on this text, an invocation of

the the Trinity, in an

elaborate development section, but the movement closes

with hushed Amens

from the chorus and soprano. [MSO historical

note: In 1963, just two

years after its premiere, The Madison Civic Chorus and

Madison Civic

Symphony—predecessors of today’s chorus and orchestra,

and then under the direction

of Roland Johnson—gave the first Midwestern

performance of this now-standard

work. - M.A.]

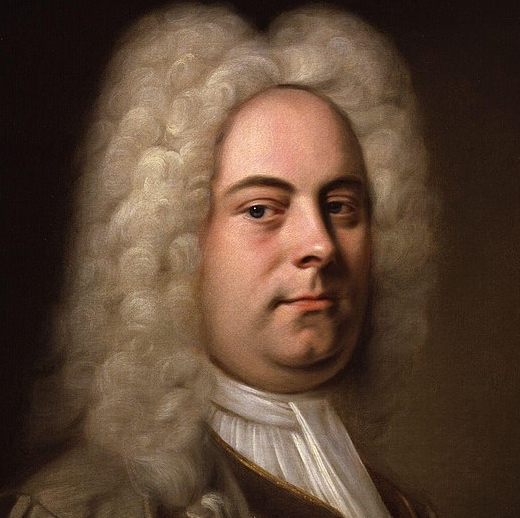

As always, we turn to Handel’s

Messiah

for the finale to our first half: the concluding Hallelujah

chorus from

Part II of the oratorio. This chorus, undoubtedly the

single most famous work

by Handel, has been a sensation since the first

performance of Messiah

in Dublin in 1742. 50 years

later, while on tour in England, Joseph Haydn heard a

festival performance of Messiah in

May of 1791, and was profoundly moved: bursting into

tears during the Hallelujah

chorus. (The experience

was a primary inspiration for his own great oratorio, The Creation, of 1798.) The chorus is

heard today in contexts that

Handel—tireless self-promoter though he was—never

dreamed of: movies, TV ads

and sitcoms, and in cover versions in styles ranging

from gospel and jazz to

rock, punk, and rap. The music is in no danger of

becoming a mere cliché,

however: it remains true to Handel’s original intent.

Following the first

performance of Messiah

in London, the

composer remarked: “My Lord, I should be sorry if I only

entertained them. I

wished to make them better.”

As always, we turn to Handel’s

Messiah

for the finale to our first half: the concluding Hallelujah

chorus from

Part II of the oratorio. This chorus, undoubtedly the

single most famous work

by Handel, has been a sensation since the first

performance of Messiah

in Dublin in 1742. 50 years

later, while on tour in England, Joseph Haydn heard a

festival performance of Messiah in

May of 1791, and was profoundly moved: bursting into

tears during the Hallelujah

chorus. (The experience

was a primary inspiration for his own great oratorio, The Creation, of 1798.) The chorus is

heard today in contexts that

Handel—tireless self-promoter though he was—never

dreamed of: movies, TV ads

and sitcoms, and in cover versions in styles ranging

from gospel and jazz to

rock, punk, and rap. The music is in no danger of

becoming a mere cliché,

however: it remains true to Handel’s original intent.

Following the first

performance of Messiah

in London, the

composer remarked: “My Lord, I should be sorry if I only

entertained them. I

wished to make them better.”

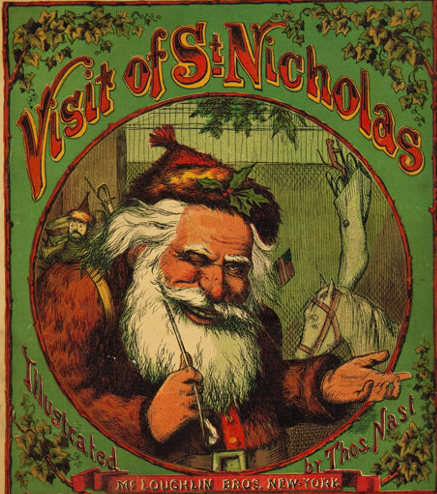

Most of our notions about Santa and his

standard operating

procedures—reindeer, rooftops, and chimneys—come straight

from Clement Clark

Moore’s classic 1823 poem A Visit From

St. Nicholas, better known today as ‘Twas the Night

Before Christmas. There

were many musical settings, but the best-known was written

by Ken Darby,

a successful film and choral

composer throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Darby’s version

became a huge hit for

Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians in 1942, in a colorful

arrangement heard

here, created by Waring’s arranger Harry

Simeone. The version heard here was further adapted

by William Schoenfeld

Most of our notions about Santa and his

standard operating

procedures—reindeer, rooftops, and chimneys—come straight

from Clement Clark

Moore’s classic 1823 poem A Visit From

St. Nicholas, better known today as ‘Twas the Night

Before Christmas. There

were many musical settings, but the best-known was written

by Ken Darby,

a successful film and choral

composer throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Darby’s version

became a huge hit for

Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians in 1942, in a colorful

arrangement heard

here, created by Waring’s arranger Harry

Simeone. The version heard here was further adapted

by William Schoenfeld

Amaury Veray

Torregrosa was

a leading figure in

Puerto Rican music from the 1950s through his death in

1995. A composer, singer,

teacher, and writer, Veray was an advocate for

preserving traditional Puerto

Rican forms in contemporary music. He

composed his most famous song, the Villancico

Yaucano

(Song

of a Man from Yauco) on Christmas Eve in 1951,

when he was leader of a

church choir in the small coastal city of Yauco, his

home town. The villancico

was a musical form that

originated in medieval Spain, but by the 20th century, villancicos were generally simple

Christmas songs in both Spain and

Latin America. Veray’s Villancico Yaucano,

sung by a humble peasant to the newborn Jesus, is heard

here in a new

arrangement by Scott Gendel.

Amaury Veray

Torregrosa was

a leading figure in

Puerto Rican music from the 1950s through his death in

1995. A composer, singer,

teacher, and writer, Veray was an advocate for

preserving traditional Puerto

Rican forms in contemporary music. He

composed his most famous song, the Villancico

Yaucano

(Song

of a Man from Yauco) on Christmas Eve in 1951,

when he was leader of a

church choir in the small coastal city of Yauco, his

home town. The villancico

was a musical form that

originated in medieval Spain, but by the 20th century, villancicos were generally simple

Christmas songs in both Spain and

Latin America. Veray’s Villancico Yaucano,

sung by a humble peasant to the newborn Jesus, is heard

here in a new

arrangement by Scott Gendel.

The Christmas Song (Chestnuts

Roasting on an Open Fire), with all of those

cozy wintertime images,

was actually written during the roasting heat of a

California summer. In his

autobiography, Mel

Tormé related the

story of how in July 1945, he drove to the home of his

lyricist and

collaborator Robert Wells in Toluca Lake. He found the

lyrics lying on the

piano, and when Wells finally appeared sweating and hot

even in shorts and a

t-shirt, he told Torme: “It was

so damn hot today, I

thought I’d write something to cool myself off. All I

could think of was

Christmas and cold weather.” Tormé replied: “You know,

this just might make a

song.” The

Christmas Song was written

in about 45 minutes later that day. Tormé quickly showed

the song to his friend

Nat Cole, whose 1946 hit recording is now a beloved

holiday classic.

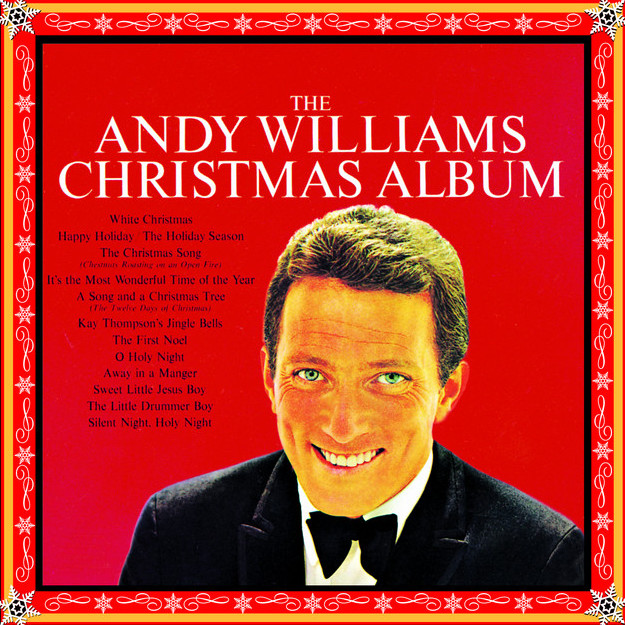

In 1963, singer Andy Williams recorded Happy

Holiday / It’s the Holiday

Season, a medley that brought together a pair

of holiday songs from the

1940s. Happy

Holiday was written by

the great American songwriter Irving

Berlin, and it was introduced in the 1942 Paramount

movie musical Holiday

Inn, where it was crooned by

Bing Crosby. Though its popularity was dwarfed by the

film’s greatest hit, White Christmas,

Crosby’s recording of Happy Holiday was

a respectable hit as

well, and other singers had covered it by 1963. It’s the Holiday Season was written in 1945

by Kay Thompson. She was a successful actress

and dancer, and music

director, and songwriter. She had been closely associated

with Williams since

1947, when a 20-year-old Williams and his three brothers

started touring with

Thompson as a nightclub act. (Thompson became a mentor to

Williams, and helped

him to develop a solo career in the 1950s.) Thompson sang

It’s the Holiday Season a few times in the

1940s, but it was not

recorded until she combined it with Berlin’s Happy Holiday in 1963 and gave it to

Williams. It became a

tremendous hit for Williams that year, together with his

cover of It’s the

Most Wonderful Time of the Year.

(These cheerful songs seem to have been a welcome escape

for Americans still reeling

from the Kennedy assassination.) Their popularity led to

several hit Christmas

albums by Williams, and a series of equally successful

television Christmas

aired from the 1960s through the 1980s—all of which earned

Williams the

nickname “Mr. Christmas!”

In 1963, singer Andy Williams recorded Happy

Holiday / It’s the Holiday

Season, a medley that brought together a pair

of holiday songs from the

1940s. Happy

Holiday was written by

the great American songwriter Irving

Berlin, and it was introduced in the 1942 Paramount

movie musical Holiday

Inn, where it was crooned by

Bing Crosby. Though its popularity was dwarfed by the

film’s greatest hit, White Christmas,

Crosby’s recording of Happy Holiday was

a respectable hit as

well, and other singers had covered it by 1963. It’s the Holiday Season was written in 1945

by Kay Thompson. She was a successful actress

and dancer, and music

director, and songwriter. She had been closely associated

with Williams since

1947, when a 20-year-old Williams and his three brothers

started touring with

Thompson as a nightclub act. (Thompson became a mentor to

Williams, and helped

him to develop a solo career in the 1950s.) Thompson sang

It’s the Holiday Season a few times in the

1940s, but it was not

recorded until she combined it with Berlin’s Happy Holiday in 1963 and gave it to

Williams. It became a

tremendous hit for Williams that year, together with his

cover of It’s the

Most Wonderful Time of the Year.

(These cheerful songs seem to have been a welcome escape

for Americans still reeling

from the Kennedy assassination.) Their popularity led to

several hit Christmas

albums by Williams, and a series of equally successful

television Christmas

aired from the 1960s through the 1980s—all of which earned

Williams the

nickname “Mr. Christmas!”

We close, as usual with a rousing Gospel

finale led by the

Mt. Zion Gospel Choir, singing music arranged for the MSO

by its codirector Leotha

Stanley. The set opens with a

pair of Stanley originals, beginning with his new song Special

Christmas Love. We

introduced the second song, Christmas Peace,

at these concerts

in 2017. The final song, sung by all three choirs is the

familiar spiritual Go

Tell it on the Mountain. This

traditional song seems to have had its origins in the

early 1800s. It was

popularized by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a remarkable

choir from Nashville’s

Fisk University, whose tours after the Civil War brought

African American music

to a worldwide audience. The most familiar version of this

spiritual was

published in 1907 by a Fisk professor and longtime

director of the Jubilee

Singers, John Wesley Work, Jr.

We close, as usual with a rousing Gospel

finale led by the

Mt. Zion Gospel Choir, singing music arranged for the MSO

by its codirector Leotha

Stanley. The set opens with a

pair of Stanley originals, beginning with his new song Special

Christmas Love. We

introduced the second song, Christmas Peace,

at these concerts

in 2017. The final song, sung by all three choirs is the

familiar spiritual Go

Tell it on the Mountain. This

traditional song seems to have had its origins in the

early 1800s. It was

popularized by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a remarkable

choir from Nashville’s

Fisk University, whose tours after the Civil War brought

African American music

to a worldwide audience. The most familiar version of this

spiritual was

published in 1907 by a Fisk professor and longtime

director of the Jubilee

Singers, John Wesley Work, Jr.

And then, friends, it’s your

turn to sing!

________