Madison Symphony

Orchestra Program Notes

November 17-18-19,

2023

98th Season /

Subscription Program 3

J.

Michael Allsen

This work, the

first symphony Mozart completed after moving to Vienna in

1781, is brilliant and

celebratory in tone.

This work, the

first symphony Mozart completed after moving to Vienna in

1781, is brilliant and

celebratory in tone.

Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart

Born:

January 27, 1756, Salzburg,

Austria.

Died:

December 5, 1791, Vienna,

Austria.

Symphony No. 35 in D

Major, K. 385, “Haffner”

•

Composed:

Composed in July and August of

1782; revised in March 1783.

•

Premiere:

The composer conducted the first

performance at the Burgtheater in Vienna on March 23,

1783.

•

Previous

MSO Performances:

1962, 1976, and 2000.

•

Duration:

23:00.

Background

The symphony

was initially a six-movement serenade, written in honor of

Siegmund Haffner, a

Mozart family friend in Salzburg. Mozart composed this

work at lightning speed—in

less than four weeks—in part to pacify his demanding

father.

In July of

1782, Mozart was at a very busy point in his career, and

making a mark in

Vienna, his newly-adopted home town. He had just completed

a successful German Singspiel,

The Abduction from the Seraglio, and had

several other projects on

the front burner, when his father wrote from Salzburg with

a request for a new

work. Leopold Mozart noted that a friend, Siegmund

Haffner, was being raised to

the nobility, and that Wolfgang should provide an

appropriately impressive new

piece for the occasion. Six years earlier, Mozart had

composed an

eight-movement serenade to celebrate a Haffner family

wedding (K.250), and

Leopold clearly had something similar in mind. On July 20,

he wrote back to his

father:

“I

am up to my ears in work. By a week from Sunday, I must

arrange my opera for

wind instruments, or someone else will do it and secure

the profits instead of

me. And now you ask for a new symphony, too! How on earth

can I do that? ...well,

I will have to stay up all night, for that is the only

way; for you, dearest

father, I will make the sacrifice. You may rely on having

something from me in

each mail delivery.”

True to

his word, he mailed the opening Allegro

a week later, but soon fell behind. A few days later, he

wrote to his father: “One

cannot do the impossible! I won’t scribble inferior

stuff—so I cannot send the

whole symphony until next mail day.” He actually had some

non-musical concerns

at that moment: his romance with Constanze Weber. He and

Constanze were married

on August 4. Leopold strongly disapproved of this

marriage, and perhaps to

mollify his father, Wolfgang was able to get five more

movements in the mail by

August 7. (Honeymoons were short in those days...) Whether

or not the music

arrived in time to be played at Haffner’s ennoblement is

not known.

Five

months later, Mozart was involved in arrangements for an

“academy” to be held

at the Burgtheater in March. In early January, wrote to

his father, asking for

the score for the serenade he had composed for Haffner. It

actually took

several letters of increasing desperation, but eventually

Leopold returned the

music. On February 15, Mozart wrote back to Salzburg:

“Most heartfelt thanks

for the music you have sent me...my new Haffner symphony

has positively amazed

me, for I had forgotten every single note of it. It must

surely produce a good

effect.” He reworked the serenade into a symphony to fit

Viennese tastes: abandoning

an introductory march (K.385a) and a second minuet (now

lost), and adding pairs

of flutes and clarinets to the outer movements. The

academy on March 23 was a

great success, playing to a packed house, and turning a

handsome profit for

Mozart. The first three movements of the symphony were

played at the beginning

of the concert, and the fourth appeared at the end,

framing a program of piano

and instrumental works (including the newly-written Piano Concerto No.13), and vocal solos.

What

You’ll Hear

The symphony is

laid out in four movements:

• A brisk

opening is sonata form.

• A calm slow movement.

• A rough-edged

minuet with a contrasting central trio.

• A fast-paced finale

that references a melody from his recently-completed opera

The Abduction from the Seraglio.

The

symphony begins with D Major fanfares from the brass: a

reflection of this work’s

original ceremonial intent. (Mozart apparently chose D

Major because it was his

father’s favorite key.) This opening movement (Allegro con spirito) might begin in this

rather festive way, but it

is not just a noisy celebratory piece: throughout the

movement, there are

constant turns to the minor and quirky modulations that

give this music a

surprisingly unsettled tone.

The two

middle movements were clearly intended for the courtly

world of Salzburg, and

sound very much like pieces from his earlier serenades.

The lovely Andante—the

longest movement in the

work—is a lightly-scored series of beautiful melodies

which are embellished and

decorated throughout. The Minuet that

follows is perhaps a bit more rough-edged than courtly.

The outer sections

sound much like Haydn, with a bit of peasant-dance

influence, but the central

trio has a more lilting quality.

The finale

(Presto)

contains an interesting

melodic reference: the main theme presented in the first

couple of measures

seems to have been based on Osmin’s final aria Ha! Wie will ich triumphieren! from The Abduction from the Seraglio. Here, Osmin

(the bad guy) is

singing “Ha! How I will rejoice when they lead you to

the scaffold, and

put the rope around your neck!” Whether Mozart was simply

reusing a good tune,

or had some darker reference in mind (maybe thumbing his

nose at the Salzburg

nobility, or Leopold?) is unknown. The mood of this

movement is mostly joyful,

though as in the opening movement, there are several

surprising turns to the

minor.

Schumann’s

Piano Concerto

is one of the leading romantic

solo works for piano, balancing virtuosity and intense

thematic development.

Schumann’s

Piano Concerto

is one of the leading romantic

solo works for piano, balancing virtuosity and intense

thematic development.

Robert

Schumann

Born:

June 8, 1810, Zwickau, Germany.

Died:

July 29, 1856, Endenich (Bonn),

Germany.

Concerto in A Minor

for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 54

•

Composed:

1833-1845.

•

Premiere:

December 5, 1845, in Dresden. The

soloist was Clara Schumann, and it was conducted by

Ferdinand Hiller, to whom

the score is dedicated.

•

Previous

MSO Performances:

1975 (Rudolf Firkusny), 1999 (Jon

Kimura Parker), and 2011 (Christopher Taylor).

•

Duration:

31:00.

Background

Schumann wrote

this work for his wife, Clara Schumann, a composer in her

own right and one of

the most prominent touring virtuosos of the period. She

made the concerto a

centerpiece of her repertoire and her many performances

over the next 40 years

helped to popularize it across Europe.

Though he

was a composer who was absolutely in love with the piano,

and a man married to

one of the great virtuosos of the age, Schumann was

notoriously unsuccessful at

producing piano concertos. There are at least three early

concertos, which were

sketched when he was in his twenties, but left incomplete.

There are also a

couple of fine single-movement works for piano and

orchestra from late in his

career, the Konzertstück

(1850) and

the Introduction

and Allegro (1853). He

only completed one concerto, however, the A minor concerto

of 1845...but it is

a really good one!

Clara and Robert Schumann

Sketches

for

the concerto date from as early as 1833, but the impetus

for completing it

seems to have been Schumann’s marriage to Clara Wieck at

the end of 1840. Their

relationship had begun when Clara was only a teenager, and

the wedding was

delayed for years by her father. Clara was just beginning

a career as a piano

soloist, and Robert had long planned to write a concerto

for her. In 1838, he

wrote to her from Vienna about this work: “My concerto is

a compromise between

a symphony, a concerto, and a huge sonata. I now see that

cannot write a

concerto for the virtuosos—I must plan something else.”

That “something else”

was a single-movement work titled Phantasie

that was a departure from the flashy but sometimes empty

virtuoso pieces that

were the mainstay of 19th century pianists. It is a gentle

and thoroughly

Romantic piece that focuses on thematic development rather

than showy

fireworks. He completed this work in 1841, and Clara

played it during a

rehearsal of Robert’s “Spring” Symphony

on August 13. He would eventually adapt the Phantasie

as the first movement of a three-movement concerto. He

completed the Intermezzo

and the finale in the summer

of 1845. On July 31, Clara wrote in her diary: “Robert has

finished his

concerto, and handed it over to the copyist. I am happy as

a king at the

thought of playing it with an orchestra.” The new concerto

was very successful

in its Desden premiere, and Clara quickly repeated in

Leipzig and Vienna. It

became the cornerstone of Clara Schumann’s solo

repertoire, and was popularized

by her many performances over the next 40 years.

Sketches

for

the concerto date from as early as 1833, but the impetus

for completing it

seems to have been Schumann’s marriage to Clara Wieck at

the end of 1840. Their

relationship had begun when Clara was only a teenager, and

the wedding was

delayed for years by her father. Clara was just beginning

a career as a piano

soloist, and Robert had long planned to write a concerto

for her. In 1838, he

wrote to her from Vienna about this work: “My concerto is

a compromise between

a symphony, a concerto, and a huge sonata. I now see that

cannot write a

concerto for the virtuosos—I must plan something else.”

That “something else”

was a single-movement work titled Phantasie

that was a departure from the flashy but sometimes empty

virtuoso pieces that

were the mainstay of 19th century pianists. It is a gentle

and thoroughly

Romantic piece that focuses on thematic development rather

than showy

fireworks. He completed this work in 1841, and Clara

played it during a

rehearsal of Robert’s “Spring” Symphony

on August 13. He would eventually adapt the Phantasie

as the first movement of a three-movement concerto. He

completed the Intermezzo

and the finale in the summer

of 1845. On July 31, Clara wrote in her diary: “Robert has

finished his

concerto, and handed it over to the copyist. I am happy as

a king at the

thought of playing it with an orchestra.” The new concerto

was very successful

in its Desden premiere, and Clara quickly repeated in

Leipzig and Vienna. It

became the cornerstone of Clara Schumann’s solo

repertoire, and was popularized

by her many performances over the next 40 years.

What

You’ll Hear

The concerto is

in three movements:

• A

lengthy movement that focuses on the development of a

single theme.

• A songlike Intermezzo. Near

the end, a reference to

the opening movement’s main theme leads directly into the

third movement.

• A bright

finale. Like the opening, this is set in sonata form, but

here Schumann spins

out several ideas.

The

opening movement (Allegro

affetuoso)

begins with a furious burst of piano chords, but soon

settles into a gentler

character, with an oboe theme that is soon picked up by

the soloist. The

movement is set in sonata form, but nearly all of the

important thematic

material is derived from this opening theme. The piano

dominates, but there are

several nice bits of orchestral writing as the soloist

plays against solo

woodwind passages. After a development that focusses on

the primary theme, and

a shortened recapitulation, the end of the movement

features the soloist in a

finely-drawn cadenza, and a shift to march character.

The lovely

Intermezzo (Andantino grazioso) is a romantic song, set

in a three-part form. The

playful opening motive—four notes passed between piano and

orchestra—is subtly

crafted from the first movement’s main melody. The central

passage, carried by

the low strings, is more lyrical and sustained. After a

short development, and

a return of the opening material, Schumann brings back a

fragment of the first movement

theme to lead directly into the final movement (Allegro vivace), whose main melody is based

upon the same material.

This movement is also set in sonata form, but where the

opening movement

focused intensely upon a single melodic idea, here the

composer seems to have

given his imagination free reign, as a whole series of

distinct melodies spring

forth in the exposition. The development begins with a

wonderful string fugato,

which is soon overlaid by yet

another new theme. The movement comes to close with a

lengthy coda—not a

crashing conclusion, but a calm and continued development

that is virtuosic

while retaining a light touch to the end.

Dawson’s symphony

brings together a host of Black musical styles, most

importantly the spiritual,

in a profound reflection on African American history.

Dawson’s symphony

brings together a host of Black musical styles, most

importantly the spiritual,

in a profound reflection on African American history.

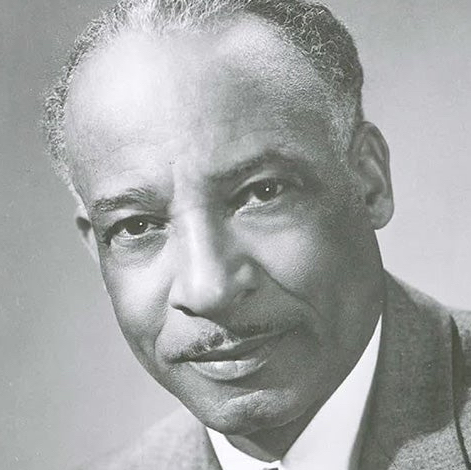

William

Levi Dawson

Born:

September 26, 1899, Anniston,

Alabama.

Died:

May 2, 1990, Montgomery, Alabama.

Negro Folk Symphony

•

Composed:

Completed 1934, revised 1952.

•

Premiere:

November 20, 1934, at Carnegie

Hall in New York City, by the Philadelphia Orchestra,

conducted by Leopold

Stokowski.

•

Previous

MSO Performances:

This is our first performance of

the work.

•

Duration:

29:00.

Background

The Negro Folk Symphony,

Dawson’s only

orchestral work, had a very high-profile premiere in 1934,

but remained

relatively obscure until the last few decades, when it has

been rediscovered by

a new generation of musicians and listeners.

William

Levi Dawson was one of the most talented African American

composers in a

generation that included Harry T. Burleigh, William Grant

Still, Florence

Price, Ulysses Kay, and others. He was born in Alabama,

and at age 15, left for

Tennessee to study at the famed Tuskeegee Institute (now

Tuskeegee University).

After his graduation, he taught public school music in

Kansas and gigged as a

jazz trombonist, while also earning a music degree at

Kansas City’s Horner

Institute of Fine Arts. Dawson spent the late 1920s in

Chicago, pursuing

additional studies at the Chicago Musical College and the

American Conservatory

of Music, while also leading a church choir and performing

on trombone. (He appeared

with Louis Armstrong and other notable jazz musicians,

while also playing

principal trombone in the Chicago Civic Orchestra!) In

1931, he accepted an

invitation to return to Tuskegee as a professor. He would

teach there until

1956, and built the Tuskeegee Choir into an

internationally-recognized

ensemble. Following his retirement, Dawson toured

extensively as a guest

conductor.

For Dawson

and many of his Black contemporaries, the spiritual was a

wellspring of

inspiration. Many of these traditional religious

songs—both “sorrow songs” and

“jubilees”—dated from the days of slavery, and the no less

turbulent late 19th

century. Dawson was involved with spirituals throughout

his life, arranging and

publishing dozens of them for chorus. Spirituals were also

the foundation for

his only orchestral work, the Negro Folk

Symphony. As he explained in his program notes for

its premiere: “In this

composition, the composer has employed three themes taken

from typical melodies

over which he has brooded since childhood, having learned

them at his mother’s

knee.” Earlier that year, Dawson showed the score to the

conductor Leopold

Stokowski, who suggested a few changes and programmed the

symphony on four

concerts performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra that

November in Carnegie

Hall. Despite an enthusiastic response from both audiences

and critics, the Negro

Folk Symphony remained largely

forgotten after this. In 1952, following a trip to West

Africa, Dawson revised

the work, particularly the first movement, to incorporate

African musical

elements, rhythm, and instruments. Stokowski finally

recorded the work, in this

new version, with the American Symphony Orchestra in 1963.

Like the works of

Florence Price (whose third symphony we played in May),

there has been renewed

interest in the Negro

Folk Symphony

in recent years.

What

You’ll Hear

The symphony is

set in three movements, each of which has a programmatic

meaning:

• A movement in

traditional sonata form that quotes a spiritual and refers

to several Black

styles.

• A slow

movement dominated by a solemn lament: a remembrance of

the time of slavery.

• An outwardly

playful finale based upon a pair of spirituals, though

also music with constant

hints of darker emotion.

The

symphony is in three movements beginning with The Bond of Africa, representing the

“missing link from a human

chain when the first African was taken from the shores of

his native land and

sent into slavery.” Dawson clearly channels Black musical

idioms throughout,

beginning with the bluesy horn and English horn solos at

the opening. (This

phrase—the “missing link”—reappears in the movement as a

kind of lament.) A

theme introduced by the oboes is the spiritual Oh, m’ Lit’l’ Soul Gwine-A Shine. The

movement continues in an

energetic classical form, with a series of themes

introduced and developed.

However, there is an overlay of references to Black styles

ranging from the juba

dance, banjo songs, and African

rhythms to contemporary Jazz and Blues.

According

to Dawson, Hope in

the Night

represents “the humdrum life of a people whose bodies were

baked by the sun and

lashed with the whip for two hundred and fifty years;

whose lives were

proscribed before they were born.” This is desolate music

beginning with a

tolling gong and a plodding background to a lament. This

idea alternates with

livelier and more hopeful music.

The main

theme of the final movement is the spiritual that Dawson

uses as its title, O,

Le’ Me Shine, Shine Like a Morning Star!

This emerges playfully in the opening section. He also

incorporates Hallelujah,

Lord, I Been Down Into the Sea.

Though the overall effect of this movement is lively and

upbeat, there are

hints of darkness intruding throughout. This is in keeping

with Dawson’s note

that it depicts “the merry play of children yet unaware of

the hopelessness

beclouding their future.”

________

program notes ©2023 by

J. Michael Allsen