Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

Overture Concert Organ

Series No. 4

April

18, 2023

J. Michael Allsen

Our final Overture Concert Organ Series

concert features our own Greg Zelek, and the welcome return

of cellist Thomas Mesa. They appeared together on this

series in 2019, and Mr. Mesa returned in November 2021 for

memorable performances of the Dvořák

Cello Concerto with the Madison Symphony Orchestra.

They open with a well-known Romantic work, which they have

adapted for the combination of cello and organ: Jules

Massenet’s famous Meditation from

“Thaïs.” Next is a pair of works by J.S, Bach, the

introspective Prelude from his Cello

Suite

No.1, and the brilliant Fugue in D Major. After an

adaptation of the Trois Pièces of Nadia Boulanger,

each performer takes a solo turn, beginning with the Boléro de Concert, a

Spanish-flavored organ work by Alfred Lefébure-Wély. Mr.

Mesa presents SEVEN, an

emotional reflection on the COVID-19 pandemic for

unaccompanied cello, written for him in 2020 by Andrea

Casarrubios. Our

finale is the world premiere of the Sonata for Cello

and Organ by the young composer Daniel Ficarri.

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Meditation

from “Thaïs” (arr. Zelek/Mesa)

Massenet was part of the generation of

French composers who came into prominence in the years after

France suffered a humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian

War of 1870-71. This was a time when the government poured

funding into French arts to make them a symbol of France’s

restored power and prestige. Massenet became a prominent

member of the National Society of Music, founded to promote

French art music, and he would eventually be a composition

professor at the Paris Conservatory. The prolific

Massenet was particularly successful in the late 19th

century as an opera composer, writing over 25 operas, though

only a few of them—notably Manon, Werther, and Thaïs—are regularly

heard today. His Thaïs

(1894) was based upon a popular novel by Anatole France,

itself a retelling of a story from the 10th century. The

opera tells the story of Thaïs, a courtesan in pagan

Alexandria, who is converted to Christianity by the monk

Athanaël. She eventually dies in glory as St. Thaïs of Alexandria, while Athanaël is

never able to shake his guilt over his sexual attraction

towards her. The opera was a bit scandalous in its time, not

only for the anti-clerical nature of the plot, but also for

the steamy scenes of Thaïs’s life before her conversion. (At

the first performance, soprano Sibyl Sanderson, singing the

title role, had a notorious—and probably

deliberate—“wardrobe malfunction” that exposed her breasts

in one scene.)

The famous Meditation is drawn

from Act II, where it is an instrumental intermezzo that

represents the moment of Thaïs’s conversion. It was already

being played as an independent concert piece in the 1890s,

and remains one of Massenet’s most popular works. It is most

often heard in the original version for solo violin, but the

piece has since been appropriated by nearly every possible

instrument, from cello, flute, and saxophone to euphonium,

harmonica, and pan flute. Heard here in an adaptation for

cello and organ, it is a gorgeous, long-breathed melody from

the cello that develops above a sonorous organ background.

There is a moment of turbulence near the middle, probably

intended to represent Thaïs’s spiritual struggle,

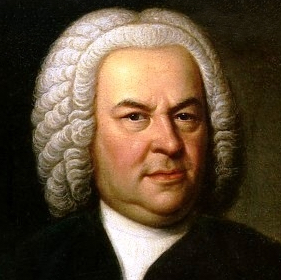

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Prelude

from

Cello Suite No.

1 in G Major, BWV 1007

Fugue from Prelude

and Fugue in D Major, BWV 532

Bach spent the years 1717-1723

in the provincial court at Cöthen, working as

Kapellmeister to the music-loving Prince Leopold of

Anhalt-Cöthen. Since the prince was a Calvinist, there was

little call for the kind of sacred vocal works and organ

music that dominated much of Bach’s career, and this was

the most concentrated period of secular composition in his

life. As the court music director, Bach had an orchestra

of 17 fine players to work with, and he responded with

many of his finest instrumental works: concertos—including

most of the famous “Brandenburgs” —his orchestral suites,

and several chamber works. Among the most amazing works he

produced during this period were two sets of pieces for

unaccompanied strings, the sonatas and partitas for

violin, and the suites for cello. Though both sets were

clearly composed for Cöthen, precisely when he wrote his

cello suites is unclear. Unlike the violin sonatas and

partitas, which Bach copied in 1720, the cello suites were

not copied until much later, in a manuscript written by

his second wife Anna Magdalena in 1728. They were most

likely composed for Carl Bernhard Lienecke, a cellist in

the Cöthen orchestra, though the sixth suite seems to have

originally composed for a Baroque variant of the cello,

the five-string violoncello de spalla. The suites

were known in the 19th century, but it was not until the

early 20th century, when Pablo Casals began to make them a

regular part of his repertoire, that they became truly

well-known. The Six Suites for Unaccompanied

Cello are now among the standard repertoire for all

cellists. Like all of the set, the Suite No. 1

includes a prelude and a collection of standard French

dances, each in two sections. Its Prelude,

certainly the best-known movement of all of the suites, is

a lovely series of harmonies laid out in a long series of

arpeggios.

Bach’s

earliest professional position, at age 17, was in Weimar,

at the court of Duke Johann Ernst III. Bach later

described his position as a “court musician,” but the

court records actually describe him as a

“lackey”—low-ranking musicians were apparently also

expected to perform more menial work as well. It is

probably not surprising that Bach left Weimar after only

six months to take a much more attractive position as a

church organist in Arnstadt, where he worked from 1703-07.

After serving in a second, more prestigious organ position

in Mühlhausen (1707-08), he was lured back to Weimar,

where he would remain until 1717, eventually serving as Konzertmeister (music director). In his

early years at Weimar, Bach concentrated primarily on

keyboard works. The court chapel had a fine

newly-renovated organ, and the Duke was apparently a great

fan of Bach’s organ works. According to Bach’s obituary,

the Duke’s encouragement “fired him with the desire to try

every possible artistry in his treatment of the organ.”

Many of the 48 preludes and fugues later published as The Well-Tempered

Clavier were written there, as were all but three of

the 46 Lutheran chorale preludes published in his Orgelbüchlein.

His Prelude and Fugue in

D Major, BWV 532, written in about

1710, was one of the most imposing works he composed in

Weimar. (The bravura style of this work made it a

particular favorite of Romantic pianists, and there are

transcriptions by Liszt and Busoni. There is also a

colorful orchestral arrangement from 1929 by Respighi.)

The Fugue, heard here, has a witty 16th-note

subject in two parts that becomes particularly impressive

when it is laid out on the pedals. Near the end, the

pedals have a short cadenza sweeping up two octaves before

a surprisingly abrupt conclusion. It is amusing to note

that one of the 18th-century manuscript copies of this

work includes the remark: “In this piece one must really

let the feet kick around a lot.”

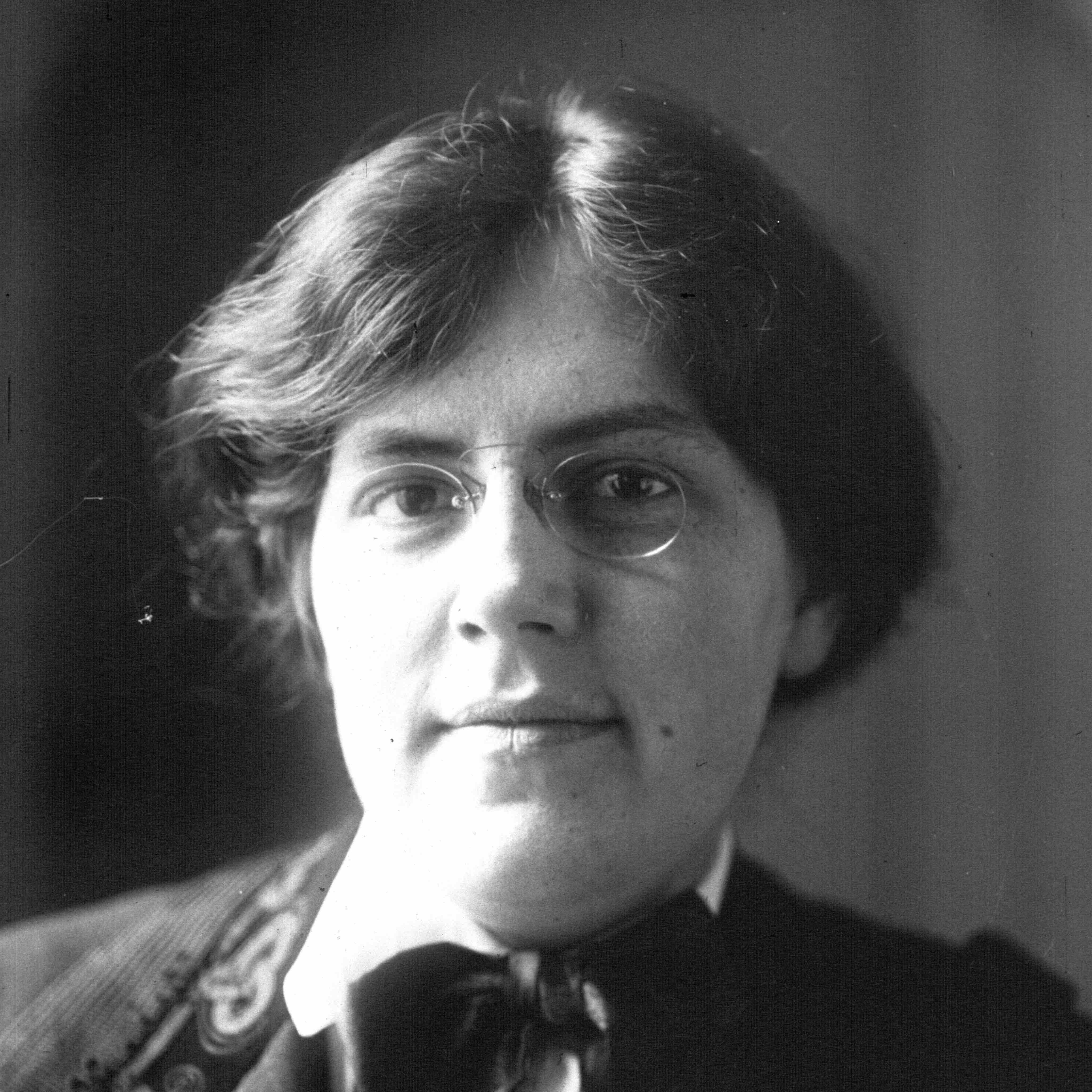

Nadia Boulanger

(1887-1979)

Nadia Boulanger

(1887-1979)

Trois Pièces for Cello and Piano (arr.

Zelek/Mesa)

Teacher, performer, and composer Nadia

Boulanger was one of the most influential women in French

music for decades. Her father taught composition at the

Paris Conservatory, and Nadia herself entered the

Conservatory at age 10. Boulanger toured extensively as a

piano soloist in the years before World War I, and she was

also a fine organist. (Aaron Copland wrote his Symphony

for Organ and Orchestra for her in 1925, and she

introduced it during an American tour.) She was the composer

of a modest number of works, primarily songs and other vocal

works, but stopped composing in the early 1920s. Boulanger

was very self-critical, often revising and sometimes

abandoning her own works. Her biographer Caroline Potter

suggests that this may have been what led her to teaching

composition, and it was in fact as a teacher that Boulanger

had the broadest impact. In a career that stretched for well

over 70 years, she taught in French conservatories,

including the Paris Conservatory, and spent the years of

World War II teaching in the United States. In 1921, she was

one of the founders of the American Conservatory at

Fountainbleau, a program that attracted the most promising

composers from the Americas. At Fountainbleu, Boulanger

taught Copland and virtually his entire generation of

American composers, as well as younger figures like Astor

Piazzolla, Leonard Bernstein, Philip Glass, and Quincy

Jones.

Boulanger’s Three Pieces for Cello

and Piano were composed in 1914. This brief set opens

with a movement marked Modéré (moderate): a lyrical

cello melody played above a gentle, transparent organ

accompaniment. When this melody repeats, it is answered by

the organ, leading to a short and more agitated middle

section, before a return to the opening character at the

end. The second movement, Sans vitesse et á l’aise

(without rushing and relaxed) has a simple, almost folklike

melody in the cello. The tempo and intensity increase

momentarily before a return of the placid main theme. The

final movement is marked Vite et nerveusement rythmé

(lively and nervously rhythmic). In its opening section, the

cello and organ constantly trade roles, each taking turns

playing a blustery dance melody and the simple accompaniment

part. There is a new theme in 5/8 that subtly continues the

rhythmic drive before a sudden slowing and an expressive

cello statement. The piece with a sudden acceleration, a

reprise of the opening dance melody by the cello and a wild

concluding passage.

Alfred

Lefébure-Wély (1817-1869)

Alfred

Lefébure-Wély (1817-1869)

Boléro de Concert, Op. 166

Alfred Lefébure-Wély was born in Paris, son of the organist at the

church of Saint-Roch. He made his public debut there at

age 8, and by age 14, when he entered the Paris

conservatory, Lefébure-Wély had also succeeded his father as organist at

Saint-Roch. He would eventually become organist at the

Paris churches of La Madeleine (1847-1858) and Saint-Sulpice (from 1863 until his death). He was a

successful composer in his time, publishing some 200

works, including an opera, and was particularly well-known as

a composer of lighter works, such as variations on popular

opera themes. He also became a fixture at the fashionable

artistic salóns of Paris’s wealthy aristocracy.

Though Lefébure-Wély was at perfectly at home on the large concert

organs of the day, including the enormous Cavaillé-Coll

instrument at Saint-Sulpice, he also published many works included intended

for the harmonium, the small, foot- pumped organ found in

upper-class French homes. One of these is his best-known

work, the Boléro de Concert, published in 1865

with a dedication to one of his aristocratic patrons, the

Comtesse Bois de Mouzilly. Spanish musical style, with its

hint of exoticism, was always popular in late 19th-century

France, and the Boléro de Concert is an adaptation

of a triple-meter Spanish dance. Much of the French organ

heard at these concerts was written to exploit the

resources of enormous concert organs, but this is music

that makes effective use of much more restricted palette

of musical colors: harmoniums had no pedalboard, and

usually just a single manual and a very limited number of

stops. (Mr. Zelek has adapted this work to include some

pedal work, but it retains the restrained character of the

original.) The Boléro de Concert begins with a

melodramatic minor-key dance theme and a chromatic second

theme. There is a brighter, major-key middle section,

before the opening music returns at the end.

Andrea Casarrubios (b. 1988)

Andrea Casarrubios (b. 1988)

SEVEN

Spanish-born cellist and

composer Andrea Casarrubios has played as a soloist and

chamber musician throughout Europe, Asia, Africa, and the

Americas. She has enjoyed increasing success as a

composer in recent years, and her works have been

programmed worldwide, presented by organizations such as

the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra, the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, the

Sphinx Organization, Washington Performing Arts, Manhattan

Chamber Players, the European Parliament, NPR, and the

Spanish National Radio. Her SEVEN for solo cello

was commissioned by Thomas Mesa, for his recording Songs

of Isolation. Composed in New York City in 2020, it

is one of an increasing number of musical works that

reflect on the experience of COVID-19. Casarrubios

provides the following note:

“SEVEN

is a tribute to the essential workers during the global

COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to those who lost lives and

are still suffering from the crisis. Written in Manhattan,

the piece ends with seven bell-like sounds, alluding to

New York’s daily 7 PM tribute during the lockdown, the

moment when New Yorkers clapped from their windows,

connecting with each other and expressing appreciation for

those on the front lines.”

One reviewer called the

work “a hauntingly beautiful tribute” and “a work that

will grip your heart and punch you in the stomach in the

most beautiful, cathartic, and absolutely necessary way.”

It is a work of quiet intensity, at the beginning working

its way through a series of solemn laments to a tense

climax. The opening mood returns briefly, before the seven

increasingly quiet “bell-like sounds” that end the work. SEVEN

is one of the most moving and effective responses to the

collective experiences we shared—without being

together—during the pandemic that I have yet heard:

expressing the isolation, sadness, and fear of the 2020

lockdown.

Daniel Ficarri (b.

1996)

Daniel Ficarri (b.

1996)

Sonata for Cello and Organ

(world premiere)

The 27-year-old organist and composer

Daniel Ficarri has already accomplished a lot in a short

time, and has been named one of the top “20 under 30” by The

Diapason (the leading trade journal of the organ

world). He studied organ with Paul Jacobs at the Juilliard

school, and studied composition with Rachel Laurin. Ficarri

currently occupies one of the most prestigious organ benches

in the United States: he is Associate Director of Music and

Organist at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York

City. He also maintains an active career as a soloist,

performing with several of them nation’s leading orchestras

and in concert halls and churches throughout the country. As

composer, he has published some two dozen works for solo

organ as well as chamber music for organ and other

instruments, and vocal and choral works. His Sonata for

Cello and Organ was commissioned for

Greg Zelek and Thomas Mesa though a generous gift from

Fernando and Carla Alvarado. The Alvarados are longtime

supporters of the Madison Symphony Orchestra, and the

Friends of the Overture Concert Organ. Ficarri provides

the following note on the work:

“I composed this cello and

organ sonata over a period of about seven months, from

March to September of 2021. The first ideas came after

listening to a friend’s performance of Strauss’s Violin

Sonata. I was struck by the feeling of conversation

between the violin and piano and felt I had something of

my own to say. I had long wanted to write chamber music

involving the modern organ, and this sonata is my first

substantial work of that type. Being an organist myself,

and having grown up as a violinist, I found a great deal

of self-expression in the combination of organ and

strings.

“The sonata is in three

movements. The first, Allegro moderato, is a

brooding sonata form movement that introduces the key

themes or characters The Adagio cantabile offers

moments of prayerful tranquility, with a playful and

whimsical middle section, Andante scherzando. The

final movement, Vivace, returns to the dark minor

key landscape, but with a triumphant conclusion. One of my

favorite elements of the sonata – the final movement

begins and ends with a thrilling dialogue between the

cellist and the organist’s feet on the pedalboard!

“Chamber repertoire involving the modern organ is rather

limited, so I pulled inspiration from works of other

instrumentation. In studying other cello sonatas, I

quickly fell in love with Brahms’s Cello Sonata No. 1

in E Minor for cello and piano. Perhaps that

subconsciously set the tone for me to write a minor-key

sonata that begins with sonata form. But in addition, I

have the greatest respect for Saint-Saëns’s Organ

Symphony in C Minor, and its expressive use of organ

and strings in the middle Adagio section in D-flat Major.

As a sort of tribute to Saint-Saëns, not only did I choose

C Minor as the key for my sonata, but I chose to make

D-flat Major a point of arrival in the first movement,

beginning the development or center of the movement. I

suppose doing those things inspired me to attempt to

write with the thoughtfulness, attention to detail, and

sincerity of that monumental work.”

________

program

notes ©2023 by J. Michael Allsen