Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

Overture Concert Organ

Series No. 3

February

25, 2023

J. Michael Allsen

Our third Overture Concert Organ Series concert brings together organist Greg Zelek and trombonist Mark Hetzler, for an imaginative program that opens with a little bit of traditional Jazz: their arrangement of When the Saints Go Marching In. They have created new adaptations of a few works specially for this program: a pair of movements from Bach’s cantatas, a movement of Mendelssohn’s “Reformation” symphony, and an enigmatic piano work by Satie. Greg Zelek presents a pair of French organ works: a prayerful piece by Boëllmann, and Widor’s exuberant Toccata. Mark Hetzler’s solo feature is a formidable contemporary work by trombonist Enrique Crespo. The program also includes three of Hetzler’s original compositions.

Traditional

Traditional

When the Saints Go Marching In

(arr. Hetzler/Zelek)

One of

the most popular early Jazz “standards,” When the

Saints Go Marching

In, seems to have

originated in the Deep

South sometime around the turn of the 20th century. It is

unclear who wrote it,

though like many Black hymns and spirituals, it may have started as an informal

“translation” of

a formal Protestant hymn— possibly a hymn published in 1896 by

lyricist

Katherine Purvis and composer James M. Black titled When

the Saints Are Marching In. Though there were several

recordings of the

tune in the early 20th century, the classic 1938 recording by

Louis Armstrong

insured its enduring popularity. The song has long been

associated with New

Orleans, and plays an important role in “second line” music.

In New Orleans

traditional funerals, the “first line” is the family and

friends of the

deceased, who walk with the hearse to the cemetery. The

“second line” is a

group of musicians who follow behind, playing solemn music on

the way to the

interment, and joyful music on the way home as the beginning

of a party

celebrating the deceased. Saints almost always kicks

off the return

trip.

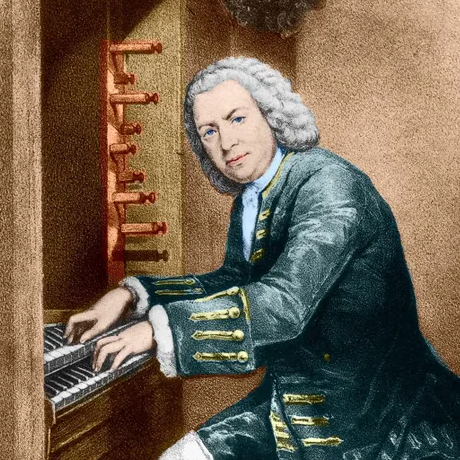

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Sinfonia

from Cantata

“Christ lag in Todes Banden” BWV 4

Aria “Höchster, mache deine Güte” from

Cantata “Jauchzet Gott in allen

Landen” BWV 51

Bach did not invent the Lutheran church

cantata, a

multi-movement setting of sacred texts, but his 200 surviving

cantatas are the

finest examples of the form. Though he composed cantatas

throughout his career,

the great bulk of them were written during his first five years

in Leipzig,

where he arrived in 1723 to take the position of Kantor at the

Thomaskirche—the

head church musician in the city. In this program, we bring

together an

instrumental movement from one of his earliest sacred cantatas

with an aria

from one of his latest.

Bach composed the cantata Christ

lag in Todes Banden (Christ

lay in

the Bonds of Death) in 1707, when he was working at his

first professional

organ position in Arnstadt. However, the piece was intended

not for Arnstadt,

but as an audition piece for a more prestigious and

higher-paid position at the

St. Blasius church in Mühlhausen. The cantata was performed

there on Easter,

and Bach was soon offered the position. This was one of his

earliest cantatas

and almost certainly his first “chorale cantata.” This was a

form Bach would

many times, in which each section of the cantata sets a verse

of a Lutheran

chorale: in this case, a well-known Easter hymn by Martin

Luther. The cantata

begins with the solemn Sinfonia heard here.

The cantata Jauchzet

Gott in

allen Landen! (Praise

God in every

nation!) was written in 1730, after the great burst of

cantata-writing in

his first years at the Thomaskirche. It is one of the

relatively few cantatas

for solo voice, in this case, a soprano. The libretto,

probably by Bach

himself, is a perfectly conventional sacred text, appropriate

to a specific

Sunday in the Church Year, the 15th Sunday after Trinity, but

Bach also added a

note to the effect that this was appropriate “all other times

as well.” The

vast majority of Bach’s cantatas were written with the highly

trained but

limited boy’s voices of the Thomaskirche chorus in mind, but

the solo part of Jauchzet

Gott in allen Landen! was clearly intended for a

professional and highly

skilled soprano. One possibility is that he wrote the solo

part for his wife,

Anna Magdalena, to be sung at some private function. (Women

did not sing in the

Thomaskirche choir.) Another possibility is that Bach wrote

this showpiece with

an eye towards impressing singers and potential patrons

outside of Leipzig. One

biographer has suggested that the cantata was written for the

leading prima

donna of the glittering Dresden court opera, Faustina

Bordini, or perhaps

for the Dresden castrato Giovanni Bindi. The cantata’s

second aria, Höchster,

mache deine Güte

(O highest God, make your goodness) features an expressive vocal

line sung above a

gentle, walking continuo. This a da capo aria, meaning

that after the

contrasting middle section—in this case, slightly more

impassioned music—is

followed by a repeat of the opening music, traditionally

ornamented by the

soloist.

Felix

Mendelssohn

(1809-1847)

Felix

Mendelssohn

(1809-1847)

Andante

from Symphony

No. 5 in D Minor, Op.107, “Reformation” (arr. Hetzler/Zelek)

Mendelssohn’s “Reformation” symphony was

written during the

fertile years of his “Grand Tour,” travelling through Europe

while he was in

his early 20s. The inspiration for the Symphony

No. 5 came during an extended visit to the British Isles.

According to one

early biographer, Mendelssohn worked out most of the details in

the fall of

1829, while he spent weeks in London convalescing from a leg

wound suffered in

a nasty carriage accident. The symphony was completed in April

1830, after he

had returned to Berlin. Mendelssohn originally planned the

symphony for a

celebration in Berlin in July 1830—the 300th anniversary of the

Augsburg

Confession, one of the central

documents of the

16th-century Lutheran Reformation. This fell through, as did

planned

performances in Leipzig, Munich, and Paris. Mendelssohn

arranged for a premiere

in Berlin in November 1832, but he was deeply disappointed by

the tepid

response and quietly set it aside. It remained unpublished for

nearly 20 years

after his death, finally appearing in print as the Symphony No. 5 in 1868.

The Symphony No. 5 is

famous for quotations of sacred melodies, particularly the

appearance of Luther’s

Ein feste Burg ist unser

Gott (A

mighty fortress is our God) in the finale. However, the

melodies of the

third movement (Andante) are

Mendelssohn’s own. These were

originally heard in the violins, but here are played by

trombone: a melancholy

main theme above a pulsing accompaniment, and a more turbulent

contrasting

idea. The opening theme returns at the end, though now the

trombone is answered

by the organ, before a quiet closing passage.

Enrique Crespo

(1941-2020)

Enrique Crespo

(1941-2020)

Improvisation No. 1

The late trombonist and composer Enrique

Crespo was born in

Montevideo, Uruguay. He was already quite successful in South

America in his

early 20s, performing as principal trombone with both the

Montevideo and Buenos

Aires orchestras. In 1967, he was offered a scholarship to

Berlin’s famed

Hochschule (Conservatory) für Musik, to study trombone and

composition. Crespo

spent the remainder of his career in Germany, performing first

as principal

trombone in the Bamberg Symphony, and later in the Stuttgart

Radio Orchestra. In

1974, he founded the German Brass Quintet, and in 1985, expanded

the ensemble

to ten players to create the German Brass. The ensemble’s first

recording was a

now-classic disc titled BACH 300, celebrating the

tricentennial of

Bach’s birth with Crespo’s arrangements of his music. The German

Brass would

eventually issue more than 20 additional recordings. As a

composer and

arranger, Crespo was able to channel a host of different styles:

folk and

popular forms from South America, Jazz and Baroque styles, and avant

garde

idioms. His Improvisation No. 1 for solo trombone comes

from 1983.

Crespo was apparently playing an audition that called for a

contemporary work.

Disappointed by the options available, he improvised this work,

later writing

it down and publishing it. It is a virtuoso showpiece,

exploiting the entire technical,

dynamic, and expressive range of the trombone, and stretching

over nearly four

octaves. Crespo hints at a few styles: Jazz ballads, traditional

“concert in

the park” trombone solos, and a funky 7/8 idea that appears

twice in the work.

Mark Hetzler (b.

1968)

Mark Hetzler (b.

1968)

Purity

Mr. Hetzler will be introducing his compositions

from the stage,

but has also provided brief notes for each. Regarding Purity,

he writes:

“I composed this music in 2018, with the goal of writing my

first ever ballad.

Knowing the difficulty of such a task, I decided to seek

inspiration from the

most important person in my life—my wife, Svetha. The piece

started out as an

instrumental, and then I invited UW-Madison First Wave Scholar

Dequadray James

White to write words to go with the music. His inspiring

poetry and powerful

singing came to life on this song, which appears on the

album Nebulebula,

the first recording produced by the Madison-based ensemble I

helped to form,

the eclectic and ever-changing Mr. Chair.”

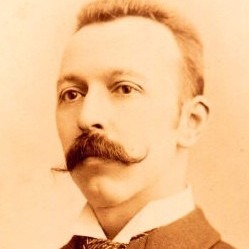

Léon Boëllmann

(1862-1897)

Léon Boëllmann

(1862-1897)

Prière à Notre-Dame from Suite

gothique, Op.25

Léon

Boëllmann left his native Alsace at age nine

to study at Paris’s École Niedermeyer,

a school dedicated to training church musicians. While there,

he studied with

Gustave Lefèvre and became a protégé of organist Eugène

Gigout, who eventually

adopted Boëllmann as

his son. After Boëllmann

graduated,

he became assistant organist, and eventually cantor and

principal organist at

the Parisian church of St Vincent-de-Paul. He spent the rest

of his tragically

brief career there though also taught at the school of

organ-playing founded by

Gigout. (Boëllmann died

at age 35, probably of

tuberculosis.) He was amazingly prolific in this short time,

managing to

publish some 150 works. The most popular of these is 1895 Suite

gothique.

Boëllmann

compose this work for the

inauguration of a relatively small new organ at the

13th-century Gothic church

of Notre-Dame de Dijon. The third movement, Prière

à Notre-Dame (Prayer

to Our Lady) was

inspired the

“black virgin” of Dijon, a wooden sculpture of the Virgin Mary

dating to the

11th century. This is quiet, meditative music with an

unhurried cantabile melody. There is a more active middle section before

a return of the

opening mood.

Mark Hetzler

Barba’s Adagio

“Yes, the title is meant to be a musical pun on

Barber’s famous

masterpiece Adagio for Strings. This work also has a

back story

connected with the group Mr. Chair. Our ensemble loves to

collaborate, working

with musicians, dancers, artists, scientists and even brewers!

We had a recent

performance that featured Madison’s own saxophone super star

Tony Barba, and

knowing that Tony loves to use electronics, I wrote this piece

so the two of us

could indulge in some sonic exploration. When Greg Zelek

invited me to perform

on tonight's concert, I thought this work would be a lot of

fun to play with

organ.”

Charles-Marie

Widor

(1844-1937)

Charles-Marie

Widor

(1844-1937)

Toccata from

Symphony No. 5 in F

minor, Op. 42, No. 1

Charles-Marie Widor had

a long career as one of France’s greatest organists, beginning

with his

appointment at age 25 as organist at the church of Saint-Sulpice

in Paris, a

position he would hold for some 64 years. In 1890, he also

succeeded César

Franck as organ professor at the Paris Conservatory, where he

would be a

powerful influence over the next generation of French organists

and organ

composers. As a composer, Widor wrote four operas and a host of

works for

orchestra, chorus, and chamber ensemble, but it is his organ

works that are

known today. Particularly popular are his ten symphonies for

solo organ. These

are large multimovement works designed to exploit the vast range

of timbres

available on a new generation of large organs, pioneered in the

19th century by

organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. The organ Widor

played at Saint-Sulpice,

rebuilt

by Cavaillé-Coll in 1862, is widely considered to be the

builder’s masterpiece.

Widor’s Symphony

No. 5 is one

of four organ symphonies he published in 1879 as his Op 42.

The composer played

its premiere on July 20, 1879, on a magnificent Cavaillé-Coll

instrument that

had been installed a year earlier in the Palais de Trocadero,

a Paris concert

hall. Its best-known movement, and by far, Widor’s most famous

piece, is its

flashy finale, the Toccata. This is a relatively

simple piece—to

understand, if not to play!—combining just two musical

elements: a repeating

harmonic pattern played on one manual (sometimes reinforced by

pedals) moving

through various keys, and a unending 16th-note decoration in

the other manual.

Musically simple, but it creates a stunning effect, building

up a tremendous

amount of inertia that is finally released in a closing

flourish and massive

final chords.

Erik

Satie

(1866-1925)

Erik

Satie

(1866-1925)

Gnossienne No. 1 (arr. Hetzler/Zelek)

Erik Satie was a quirky guy. He was certainly

one of the

most unorthodox composers of France’s “Belle Époque”—the period

between the end

of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and the beginning of World

War I in 1914

that saw radical changes in music and all of the arts. Satie

spent his entire

career in Paris. He would eventually become a success when he

was in his

mid-40s, when his innovative works were championed by Ravel and

other younger

composers. But for much of his career, Satie worked in relative

obscurity,

producing music that was unconventional in style, and often

satirical in tone

or simply absurdist: his works include Flabby Preludes for a

Dog, Three

Pieces in the Form of a Pear, and

Sketches and Provocations of a Portly Wooden Mannequin!

He

cultivated an equally strange personal image: his eccentricities

included

eating only white food and dressing every day in one of several

identical

velvet suits.

His Trois Gnossiennes—three

short piano pieces

composed in 1890 and published in 1893—seem to refer to

Gnosticism, an ancient

and mystical belief system stressing esoteric knowledge and gnosis,

or personal

understanding. It was very

much in the air in turn-of-the-century France. The Gnostic

Church of France was

founded in 1890, and Satie himself was formally associated the Mystical Order of the Rose and Cross of

the Temple and Grail (a Parisian offshoot

of the widespread Rosicrucian

movement).

Just how the Trois Gnossiennes might express

this is unclear, but

they are rather mysterious and deceptively simple little

pieces. The Gnossienne

No. 1 was published without barlines, though it seems to

be a slow and

rather wistful dance. In this adaptation, the organ plays the

unvarying

accompaniment and the trombone plays the sometimes modal,

vaguely

oriental-sounding melody. The piece unfolds in a series of

short repeated

segments. Along the way the way, Satie provides rather obscure

expressive

directions: très luisant (very radiant), questionnez (ask), du bout de la pensée

(deep in

thought), postulez en vous-même (make demands on yourself), and

sur la langue (on the tip of the tongue).

Mark Hetzler

Infinity

“This composition got its start in 2010 as a

chamber piece for

trombone, two pianos and percussion, with the title Three

Views of Infinity.

In 2016, I orchestrated the entire work to be performed as a

trombone concerto

with full symphony orchestra. The piece was inspired by visits

to India with my

wife and her family, and includes influences from South Indian

Classical Music,

Religious Chanting, Minimalism, Romanticism and American

Popular Music. Infinity,

the finale movement of the concerto, is about a wild car ride

across South

India. I dedicated this piece to my wife and her parents, who

became U.S

citizens in 1987.”

________

program

notes ©2023 by J. Michael Allsen