Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

Overture Concert Organ

Series No. 2

October 25, 2022

J. Michael Allsen

We

welcome organist Christopher Houlihan for this second

concert of our organ series. He opens with one

of the most

frequently-played works by Bach, the Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543. Robert Edward Smith’s An

Introduction to the King

of Instruments will be an

enjoyable “guided tour” of the Overture Concert Organ...narrated by our own Greg

Zelek. Mr. Houlihan concludes

with Franz Liszt’s monumental Fantasy

and

Fugue on “Ad nos, ad salutarem undam.”

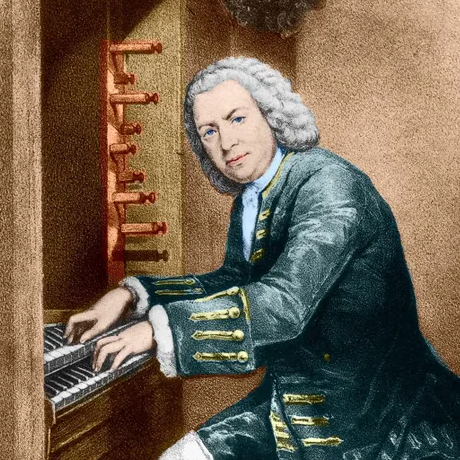

Johann

Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750)

Johann

Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750)

Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543

Bach’s

earliest professional position, at age 17, was in Weimar, at

the court of Duke

Johann Ernst III. Bach later described his position as a

“court musician,” but

the court records actually describe him as a

“lackey”—low-ranking musicians

were apparently also expected to perform more menial work.

It is probably not

surprising that Bach left Weimar after only six months to

take a much more

attractive position as a church organist in Arnstadt, where

he worked from

1703-07. After serving in a second organ position in

Mühlhausen (1707-08), he

was lured back to Weimar. The court organist, Johann Effler,

had finished

extensive renovations to the organ in the Duke’s chapel, but

his health was

failing. Knowing Bach’s growing reputation as an organ

virtuoso and as an

expert on organ construction, Effler invited Bach to Weimar

to inspect the

instrument and play an inaugural recital for the Duke in

June of 1708. Bach was

immediately offered the position of court organist. (Don’t

worry: the ailing

Johann Effler was able to retire comfortably, with his full

salary!) By July

1708, Bach was in Weimar, where he would remain until 1717,

eventually serving

as Konzertmeister

(music director).

.

In his early years at Weimar, Bach

concentrated primarily on

keyboard works: many of the 48 preludes and fugues later

published as The

Well-Tempered Clavier were written

there, as were all but three of the 46 Lutheran chorale

preludes published in

his Orgelbüchlein.

The Prelude and Fugue

in A minor also comes

from this productive period. One of the prime influences on

this work—and on

many of his early organ works—was the style of his

acknowledged master,

Dieterich Buxtehude. In 1705, the 20-year-old Bach took a

leave from his church

position in Arnstadt to walk 280 miles to Lübeck, where he

hoped to study with

Buxtehude—the only truly long journey Bach ever made. Though

he was not exactly

AWOL from Arnstadt, his employers complained that Bach had

requested a

four-week leave, but stayed away for “about four times that

long.” Just how

much he actually studied with Buxtehude is unclear, but

several of his organ

works over the next few years—including the masterful Prelude and Fugue in A minor

heard here—clearly show his admiration for Buxtehude’s

music.

The Prelude begins

with a winding, subtly chromatic line in the manuals,

eventually joined by a

long-held pedal. The pedals and manuals then begin to

explore the opening

material together, all the way through to a dramatic

conclusion. The Fugue

is set in 6/8, lending a dancing

quality to this intensely complex work. In the opening, the

fugue subject is

presented four times, lastly by the pedals. The fugue

includes some long,

chromatic episodes—typically passages without the fugue’s

opening subject,

though Bach subtly manages to work in fragments of this

theme. The ending is

dramatic: the writing for the manuals fades away, leaving

the pedals exposed

for a final showy passage. The work ends with a brilliant

flourish from the

manuals.

Robert

Edward

Smith (b. 1946)

Robert

Edward

Smith (b. 1946)

An

Introduction

to the King of Instruments: Variations on an American

Folk Tune

Composer, harpsichordist, and church

musician Robert Edward Smith joined

the faculty of Trinity

College (Hartford, CT)

in 1979 and served as composer-in-residence

there.

He also taught at the Hartt

School of Music from 1995-2011. As a composer, Smith

has written music

for vocal and instrumental ensembles of all sizes ranging

from unaccompanied

viola to symphony orchestra, as well as the 2011 chamber

opera A

Place of Beauty,

on the life of art collector and philanthropist Isabella

Stewart Gardner. His

published music includes many sacred choral pieces and works

for organ. As a

harpsichordist, Smith holds the distinction of being the

first person since the

18th century to perform in public the complete harpsichord

literature of

François Couperin. He was also a working church musician for

nearly 50 years. Smith

currently lives in Boston and devotes himself to

composition. He

composed the work heard here in 1978, and notes that:

“The

variations were composed on commission from Michael Nemo,

who was the founder

of Towerhill Records. He wanted to produce a recording

that illustrated to the

listener what sounds a well-designed pipe organ could

produce, taking as his

model Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra.

The commission

was specifically for the recording, and would feature John

Rose as organist

playing the organ at Saint Joseph’s Cathedral in Hartford,

CT. Mr. Rose

performed it live at Trinity College Chapel in Hartford

after the recording was

made.”

This

is one of a few works by Smith that draw upon the rich

heritage of early

American hymnody. In this case, it is the tune Pisgah. This melody, attributed to J.C.

Lowry (possibly Joseph C.

Lowery), which first appeared in the shape-note collection The Kentucky Harmony in 1816. “Shape-note” or “Sacred Harp”

music is a uniquely

American tradition, beginning in the late 18th century.

Four-part hymns,

anthems, and “fuging tunes” were printed in a notation in

which

variously-shaped noteheads represented solfege syllables.

This music often has

a rough-edged, sturdy beauty, and many of these tunes

survive in modern

hymnals. In the case of Pisgah, it is

usually paired with the 18th-century Isaac Watts hymn When I Can Read My Title Clear. In

describing the variations, Smith

writes:

“Each

variation features a particular rank of pipes: principals,

flutes, reeds,

mixtures, etc., each of which is introduced by the

narrator. After the

last variation, the work ends with a rondeau, which

repeats the order of ranks

presented in the variations, but without the vocal

introduction. The rondeau

ends with its theme played above the hymn tune as a sort

of hymn descant.”

Franz

Liszt (1811-1886)

Franz

Liszt (1811-1886)

Fantasy

and

Fugue on “Ad nos, ad salutarem undam”

Franz Liszt was the preeminent piano

virtuoso of the 19th

century, and the model for many pianists to follow. He was

also an imaginative

and ground-breaking composer, but as a young man, he was so

much in demand as a

soloist that he was allowed little time to develop his

composing skills. Liszt’s

concert tours in the 1830s and 1840s were nothing short of

sensational—contemporaries

used the term “Lisztomania” to describe the frenzy

surrounding his playing. He

performed hundreds of concerts to packed houses throughout

Europe, and produced

for the most part compositions that focused on his own

technical showmanship,

rather than musical content.

It was not until he settled in Weimar in 1848, taking a

secure and stable job

as music director to the Weimar court, that Liszt’s music

takes a turn away

from these showy pieces.

In 1848, Liszt

attended the premiere of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s huge,

five-act grand opera Le prophète in

Paris and was deeply

impressed. Le

prophète, set against

the background of Dutch religious upheaval in the early

16th century, is based

upon the life of the Anabaptist leader John of Leiden.

John was able to

establish a religious state in the city of Münster,

proclaiming himself “King

of New Jerusalem,” before his eventual downfall and death

by torture. Liszt

studied Meyerbeer’s score closely, and in 1849-50

completed a set of three Illustrations du

Prophète for solo

piano. Virtuoso transcriptions of music from popular

operas were nothing new at

the time—Liszt himself had written dozens of them in

previous years—but the Illustrations du

Prophète were built on

another scale. This set, lasting nearly 40 minutes in

total, very freely adapts

Meyerbeer’s music, sometimes reordering and fragmenting

themes to make new

musical connections. In the winter of 1850, he completed

what was essentially a

fourth Illustration

from the opera,

his Fantasy and

Fugue on “Ad nos, ad salutarem undam”—this

one written not

for piano but rather for organ. Liszt became interested in

the organ during in

his Weimar years, at least partly inspired by a deep

reverence for Bach—who had

of course held the same the same job as Liszt in Weimar

135 years earlier. The Fantasy

and Fugue was the first of some 45

works for organ Liszt

would compose over the next 20 years. However, though

Liszt was a phenomenal

pianist, he was less skilled as an organist; in

particular, he never seems to

have mastered the pedals. The work was premiered by one of

his students,

Alexander Winterperger, as part of the dedication of a new

organ in Merseberg

Cathedral, on September 26, 1855.

The Fantasy

and

Fugue is

an enormous virtuoso

work, sprawling over some 765 measures, and lasting nearly

half an hour. In the

opera, the chorale Ad

nos, ad salutarem undam (Come

to us, to the

waves of salvation) is sung by a trio of sinister

Anabaptist priests, who

will eventually have a hand in John of Leiden’s

destruction. It appears in the

opera’s first act, as the priests recruit peasants to

start a religious

rebellion. Meyerbeer apparently found the melody in a

17th-century hymnal. Liszt’s Fantasy and Fugue

is laid out in three

large sections, opening with a brief and dissonant

introduction, before he

introduces the rather creepy chorale melody. After a

mysterious, atmospheric

transition, Liszt begins a long, free development of this

theme. After the

music reaches a roaring climax, there is another quiet

transition into the

second large section (Adagio). This

opens with a simple, unadorned statement of the melody,

and moves through six

calm variations. This section closes with an agitated and

highly dissonant

passage—Liszt makes extensive use of the whole-tone scale

here—that leads into

the Fugue. In

keeping with the

dimensions of the Fantasy,

the Fugue is

massive, some eight minutes

long. This was the first time Liszt used a fully-developed

fugue in his works,

though he uses a thoroughly unorthodox version of this

traditional form. The

piece ends with a colossal, fiercely triumphant statement

of the chorale.

________

program

notes ©2022 by J.

Michael Allsen