Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

Overture Concert Organ Series No. 1

September 27, 2022

J. Michael Allsen

This

opening program of

the 2022-23 Overture Concert Organ Series features the

Madison Symphony

Orchestra’s principal organist, Greg Zelek, and begins with

the premiere of a

work dedicated to him, the brilliant Toccata

by Paul Fey. The next work is Zelek’s own adaptation of the

impressionistic Clair

de lune by Claude Debussy. After a

pair of masterful fugues written by a very young J.S. Bach,

Zelek presents two

American works: John Weaver’s virtuosic Fantasia,

and the lush, romantic Adoration by

Florence Price. The

closer is César

Franck’s

Grande Pièce Symphonique, a landmark work from

19th-century France.

Paul

Fey (b. 1998)

Paul

Fey (b. 1998)

Toccata

(premiere

performance)

The

young German composer

and organist Paul Fey was born in a small town near Leipzig.

After initially

studying classical guitar and piano, he discovered the pipe

organ at his local

church when he was a teenager. Fey notes that “I went on to

practice and

experiment on this instrument for several hours at a time,

never once getting

tired of all of the possible combinations of the different

timbres. The pipe

organ increasingly gripped my full attention, so I put the

guitar lessons ‘on

hold’ in order to get my first organ lessons from A.F.

Kipping, as well as

studying with Stefan Kießling (the former assistant organist

at the St. Thomas

Church in Leipzig).” He

later studied

organ and sacred music at the University of Halle. Today, in

addition to

working as an organist, Fey produces an extensive YouTube

channel featuring

performances of both his own music and the music of other

organ composers. The

Toccata

premiered here was commissioned by William Steffenhagen, a

longtime member of

the Friends of the Overture Concert Organ. The work is

dedicated to Greg Zelek.

According to Fey, Mr. Zelek requested something “shiny and

exciting”—and the Toccata

is certainly successful on both

counts! It opens with a fiery set of figures on the manuals,

and then the

pedals provide a melody to go with this accompaniment. After

a brief

contrasting section, Fey provides a short pedal cadenza,

which he says “should

be pretty interesting for the audience to watch.” The Toccata closes with a brief reprise of the

opening music and a powerful

ending.

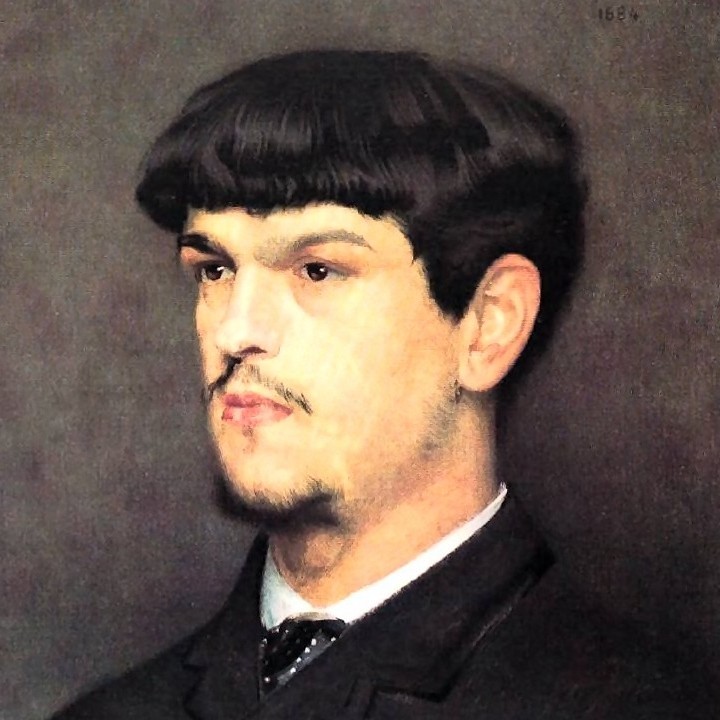

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Clair de lune (arr. Greg Zelek)

As a young man, Claude

Debussy earned a reputation, in

Paris at least, as

one of the late 19th century’s great pianists: not in

the large-scale flashy

public concerts typical of virtuoso performers but as a

young “bohemian” in the

cool, intellectual atmosphere of Paris’s cafés and

artistic salons. His Clair de lune (Moonlight) is the third movement of the Suite Bergamasque for solo piano. It was

written in about 1890 and

revised prior to its publication in 1905. Inspired by a

Symbolist poem by his

friend Paul Verlaine,

Clair de lune

is quite possibly Debussy’s best-known work. It has been

adapted for innumerable

instruments and ensembles. In Greg Zelek’s sensitive

adaptation for solo organ,

its lush and sensuous melodic line is played above a

shimmering and static

harmonic background.

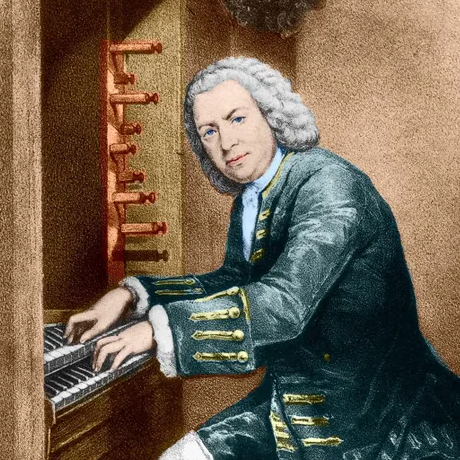

Johann

Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750)

Johann

Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750)

“Little” Fugue in G minor, BWV 578

“Gigue” Fugue in G Major, BWV 577

J.S. Bach was of course the grandmaster

of the Baroque

fugue, and this program features two examples of the form,

both composed when

he was a young man. Bach’s “Little” Fugue

in G minor (so-named to distinguish it from the

slightly longer “Great”

Fantasia and Fugue in G minor, BWV 542) was

composed sometime

before 1707, when Bach was in Arnstadt, serving as organist

in in the Neukirche

(“new church”) there. Bach at age 18 had taken a position as

musician at the

court of Weimar, but he quickly found a better post at

Arnstadt. A small city

in central Germany, about 40 miles from Bach’s hometown of

Eisenach, Arnstadt

was a fairly provincial and rather dull place at the time,

but it proved to be

a good initial position. Bach had a particularly fine new

organ to work with,

and set about composing an impressive set of works for the

instrument,

including this famous fugue.

The “Gigue” Fugue in G

Major was often regarded as spurious—as a work

misattributed to Bach—but

recent writers tend to support his authorship. It also seems

to have been a

relatively early work, perhaps as early as his first

professional organ jobs in

Arnstadt (1703-07) or Mühlhausen (1707-08). The “Gigue” Fugue, named for its lively subject in

gigue (or jig) rhythm, is remarkably similar

to a couple of works

by the composer Dieterich Buxtehude, particularly his “Gigue” Fugue in C Major. This musical

connection makes perfect

sense in a work by the young Bach, who admired Buxtehude

above all other

composers. While was working in Arnstadt, Bach famously took

a four-month leave

to walk the 280 miles to the northern port city of Lübeck in

order to study

with Buxtehude. Bach’s “Gigue” Fugue

is a bravura piece with particularly impressive pedal lines.

Its dancelike

texture builds up a tremendous rhythmic tension that only

resolved in the final

measures.

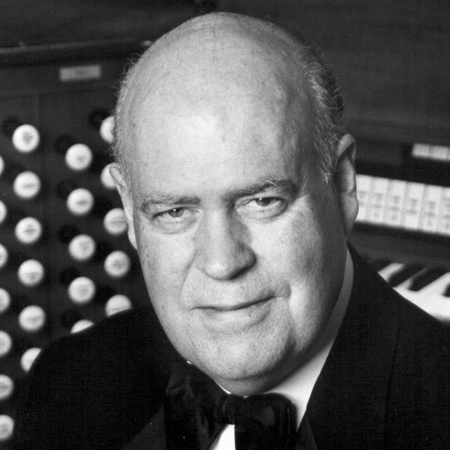

John Weaver (1937-2021)

John Weaver (1937-2021)

Fantasia

Born in Pennsylvania, organist and

composer John Weaver

taught organ at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and

also served as head of

the organ department at New York’s Juilliard School. In

1970, he was appointed

organist at the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church in New

York City, a position

he held until his retirement in 2005. His 1977 Fantasia is a

brilliant

showpiece for both the organist and the organ.

It is in four connected sections, with the opening Allegro based upon a restless,

forcefully-accented theme. The

Scherzo

playfully explores the idea

above long-held pedals, before moving into a more

mysterious and modal Adagio. The Finale presents a brilliant, contrapuntal

version of the opening

idea.

Florence

Price

(1887-1953)

Florence

Price

(1887-1953)

Adoration

The music of Florence

Price has

attracted tremendous

interest in recent years—and justifiably so: here is an

20th-century American

composer of the first rank, whose works have largely been

rediscovered only in

the last dozen years. Greg Zelek has already taken part in

this “Price

Renaissance,” performing her Suite No. 1

here last season, and recently making one of the first

recordings of the piece.

At this program, he performs her Adoration. Born in Little

Rock, Arkansas, into a

well-respected family—her father was the only Black dentist

in this strictly

segregated city—Price studied at the New England

Conservatory of Music. She

then taught music for several years in Atlanta and Little

Rock, but following a

lynching in Little Rock in 1927, her family resettled in

Chicago, where she

would spend the rest of her life. It was in Chicago that

Price finally began to

have success as a composer, culminating in 1933, when her Symphony No.1 was performed by the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra—the

first work by an African-American woman to be played by a

major orchestra.

Though her music was performed and championed by star

performers like Marian

Anderson, she struggled to make ends meet throughout her

life. Price studied

organ at the New England Conservatory, and played frequently

in Boston as an

organ accompanist and soloist. After graduation, she briefly

worked as a church

organist at the Unitarian Church in Nantick, Massachusetts,

but it is unclear

whether or not she ever had a regular church position after

this. However,

after moving to Chicago, Price studied at the American

Conservatory of Music’s

newly-established School of Theatre Organ, and worked

frequently as a theatre

organist for the next few years. She was also part of the

Chicago Club of Women

Organists, and she frequently performed at the club’s

concerts, often

presenting her own music. Unlike the great majority of

Price’s organ works, Adoration

was actually published during

her lifetime, appearing in print in 1951. The style of this

brief work is

thoroughly romantic, with the opening section setting a

lovely, lyrical tune.

After a short transition there is a contrasting episode: an

equally lyrical

melody with a chromatic accompaniment.

The piece ends with a return of the opening music and

a hushed

ending.

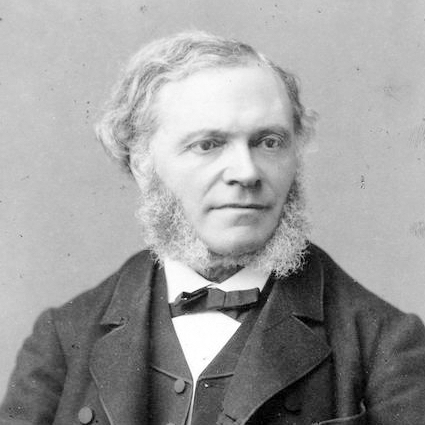

César Franck (1822-1890)

César Franck (1822-1890)

Grande Pièce Symphonique, Op. 17

The Belgian-born organist and composer

César Franck cast

a long shadow over the organ

music of 19th-century France. He began studies at the Paris

Conservatory as a

teenager, but never completed his studies there. He

eventually returned to

Paris in 1845, securing a series of increasingly prestigious

organ jobs that

culminated in his appointment as organist at the church of

Sainte-Clothilde in

1858. In 1872, Franck acquired the most influential organ

position in France:

he became organ professor at the Paris Conservatory,

remaining there until his

death in 1890. Franck gathered a large and devoted group of

students that

included Louis Vierne, Vincent D’Indy, and Ernest Chausson.

Like many of his organ works, the Grande Pièce Symphonique, completed in 1862,

was designed for the

new style of large organ pioneered by the French builder

Aristide

Cavaillé-Coll. This work was one of several Franck composed

shortly after

Sainte-Clothilde installed a new Cavaillé-Coll instrument in

1859. It is also

an experiment in applying symphonic form to a work for solo

organ: it is set in

three large movements, and in true symphonic form, Franck

develops a few main

themes across all movements. The opening Andante

serioso is an introduction, based upon a wandering

line and a gentle

syncopated idea. After a climactic conclusion, this leads

into the main body of

the movement (Allegro

non troppo e

maestoso), set in sonata form. There are two main

ideas: a forceful main

theme, and a gentler chorale-style second theme. In the

brief development

section, Franck refers to the syncopated idea from the

introduction, before the

pedals begin a quiet recapitulation of the main themes. The

theme from the

introduction makes a hushed appearance in the final

measures. The slow movement

(Andante) develops

a lyrical, richly

chromatic idea heard at the beginning. There is an abrupt

change in character

and tempo (Allegro)—essentially

the

“scherzo” of symphonic form. This restless minor-key episode

eventually closes

with a short fanfare before returning to the Andante theme to close the movement. The

closing movement (Allegro

non troppo e maestoso) begins

with a review of themes from the previous two movements,

linked by statements

of the first movement’s Allegro theme

in the pedals. An exalted version of this Allegro

theme then emerges as the main idea of this movement. After

an extended fugue

on this theme, Franck ends his Grande

Pièce with

a suitably grand coda.

________

program

notes ©2022 by J.

Michael Allsen