Madison

Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

March

19, 2023

One of

our more popular features over the past few seasons

have been presentations in

the Beyond the Score® series developed by the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra. These

innovative programs combine live actors, multimedia,

and the orchestra to

present deep and entertaining background on a featured

work—followed by

performance of the full work. At this program, led by

our Associate Conductor,

Kyle Knox, actors James Ridge, Colleen Madden, and

Gavin Lawrence from American

Players Theatre will be on stage for the story of

Mahler’s joyous Symphony No.4.

Soprano Emily Secor will

sing the final movement: a song describing a child’s

colorful vision of Heaven.

Mahler’s

Symphony No 4,

the smallest and most joyful of his symphonies, was

completed during his

stressful first years as conductor of the Vienna

Philharmonic.

Mahler’s

Symphony No 4,

the smallest and most joyful of his symphonies, was

completed during his

stressful first years as conductor of the Vienna

Philharmonic.

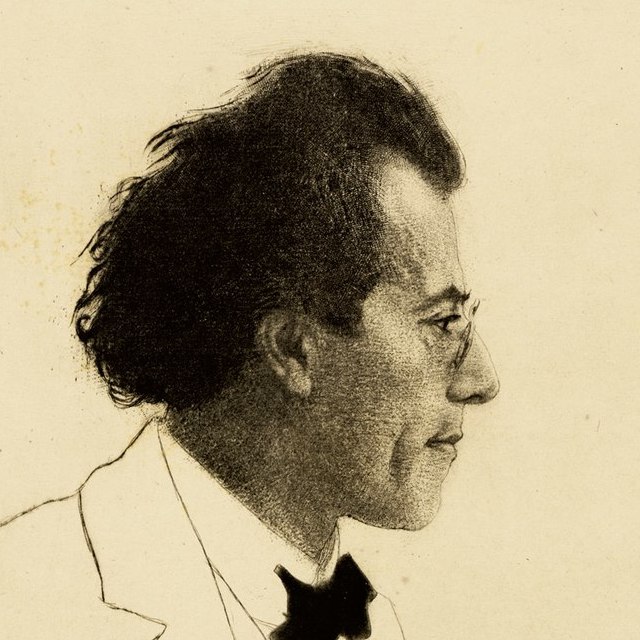

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7,

1860, Kalischte, Bohemia.

Died: May 18,

1911, Vienna, Austria.

Symphony No. 4 in G Major

-

Composed: Mahler composed the fourth movement in 1892. The opening three movements were written during the summers of 1899 and 1900.

-

Premiere: November 23, 1901 in Munich, with Mahler conducting the Kaim Orchestra.

-

Previous MSO Performance: 1969 (with Bettina Bjorksten as soloist), 1985 (Lorna Haywood), 1998 (Helen Donath), and 2016 (Alisa Jordhelm).

-

Duration: 57:00.

Background

Des

Knaben Wunderhorn (The

Boy’s Magic Horn), a collection of folk poetry, had a

profound effect on Mahler.

He set several of these poems to music early in his

career, and the poems were

in the background of the first four of his symphonies,

including the vocal

finale of the fourth.

Mahler’s fourth symphony represents a

kind of peaceful

interlude in his series of works: not only is it

something of a miniature by

Mahler’s standards (a work of less than an hour’s

duration, scored for a

relatively modest orchestra), it is almost completely

upbeat and joyful. This

is not the fierce, triumphant joy that closes the second

symphony, nor is it

the exaltation that ends the third—here, it is a simple,

childlike joy that

pervades most of the symphony and reaches its purest

expression in the fourth

movement’s song.

This

joy does not reflect the stress of Mahler’s life at the

time. In 1898, he accepted the post of Music Director

for the Vienna

Philharmonic, at that time the best orchestra in the

world. Mahler had converted

to Catholicism as part of his campaign for this

position, but antisemitism

remained a hindrance throughout his time in Vienna. His

authoritarian style did

not please the musicians, and his unorthodox and highly

personal

interpretations drew fire from conservative Viennese

critics. The upside of all

this controversy was that ticket revenues soared, and

that management loved

him! He eventually resigned his post in 1901. Mahler’s

output as a composer

fell in 1898, even during his preciously-guarded summer

holiday. In the summer

holiday of 1899, however, he had a burst of creativity

and sketched out much of

the opening three movements, finishing them the

following summer.

This

joy does not reflect the stress of Mahler’s life at the

time. In 1898, he accepted the post of Music Director

for the Vienna

Philharmonic, at that time the best orchestra in the

world. Mahler had converted

to Catholicism as part of his campaign for this

position, but antisemitism

remained a hindrance throughout his time in Vienna. His

authoritarian style did

not please the musicians, and his unorthodox and highly

personal

interpretations drew fire from conservative Viennese

critics. The upside of all

this controversy was that ticket revenues soared, and

that management loved

him! He eventually resigned his post in 1901. Mahler’s

output as a composer

fell in 1898, even during his preciously-guarded summer

holiday. In the summer

holiday of 1899, however, he had a burst of creativity

and sketched out much of

the opening three movements, finishing them the

following summer.

One of Mahler’s inspirations in this

period was Des

Knaben Wunderhorn (“The Boy’s Magic

Horn,” 1805-1808) a collection of German folk-poetry,

collected and heavily edited

by the German poets Achim vom Arnim and Clemens

Brentano, together with some of

their own poems. These texts, filled with folk-religion

and fairytale

imagery—an idealized version of country life—were hugely

popular among the

German Romantics. Several composers, Weber, Mendelssohn,

Schumann, and Brahms

among them, set Wunderhorn

texts to

music. But the collection was a particularly powerful

source of inspiration for

Mahler, generating several song-settings and playing a

role in the creation of

his first four symphonies, three of which include solo

settings of Wunderhorn

poems. These texts seem to

have had a special significance for Mahler, who viewed

these simple, sometime

naïve poems as symbolic of events in his own life.

The three movements written in

1899-1900 were composed to

complement a work written some eight years earlier. In

1892, Mahler wrote an

orchestral setting of the poem Das

himmlische Leben (“The Heavenly Life”) from the Wunderhorn collection. His setting of this

poem went through two

different incarnations before it found a home in the Symphony No.4. It was originally an

independent song for soprano

and orchestra, but then in 1896, Mahler included the

piece as the seventh

movement of his enormous Symphony No.3,

with the title “What the Child Tells Me.” He abandoned

this plan, and set the

movement aside. It eventually found a home as the core

of Symphony No.4. The opening three movements

serve as preparation for

this sublime song—according to Mahler: “In the first

three movements, there

reigns the serenity of a higher realm, a realm strange

to us, oddly

frightening, even terrifying. In the finale, the child,

who in his previous

existence belonged to this higher realm, tells us what

it all means...”

What You’ll Hear

The symphony is in four movements:

• A large opening movement

that develops two distinct themes in an innovative way.

• A rather sinister scherzo,

featuring the solo violin in the guise of a demonic

fiddler.

• A tranquil slow

movement.

• The concluding movement

is a song for solo soprano, setting a poem from the Wunderhorn collection.

The opening movement is set in an

unorthodox sonata form. The

opening bars set a pastoral mood with a chirping

combination of flutes and

sleighbells—a motto that serves to mark off the sections

of this form, and

which will reoccur in the finale. The exposition

continues in perfectly

Classical form, as two main ideas are introduced. The

first of these is a

lilting melody introduced by the strings and picked up

by the solo horn and

woodwinds. The second, much more sonorous and flowing,

is heard in the cellos. A

wry little episode for oboe, bassoon, and clarinet

rounds off the exposition,

and the sleigh bells begin a lengthy development section

which works out the

material laid out previously, and moves gradually

towards one of the few

forceful moments in the symphony, led by the trumpets—a

moment that quickly

subsides. The recapitulation, also signaled subtly by

the motto, brings back

the main thematic material, but out of order and in

transformed fashion. The

clearest statement of the opening theme is reserved for

the very end, just

before a brief, sparkling coda.

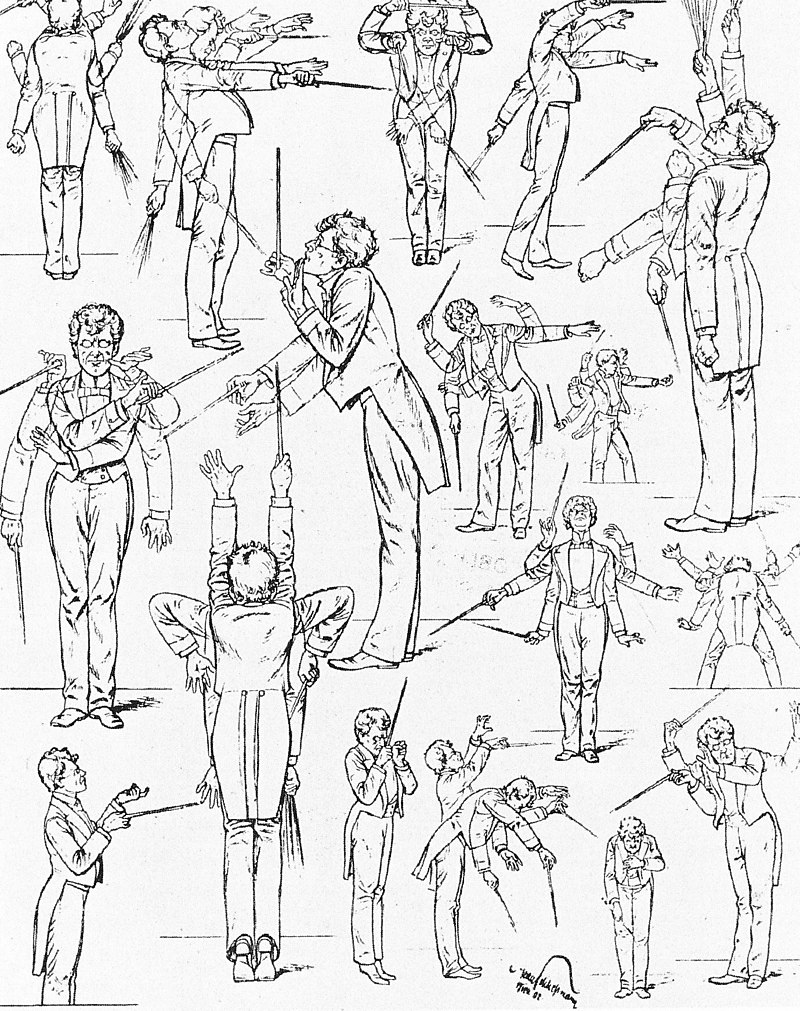

Death Playing the Fiddle, 1872

Mahler’s original title for the

second movement was Freund Hein spielt

auf (“Friend Hein

plays”). Hein, a figure from Austrian folktales, was a

demonic fiddler who led

people into Hell with his playing. Also in the

background of this deliberately

spooky movement is a self-portrait by the Romantic

painter Arnold Böcklin, a

picture that shows the artist listening as the figure of

Death fiddles just

behind his shoulder. True to the subject-matter, much of

the scherzo is carried

by fiddling from a solo violin. (Mahler directs that the

violinist tune all

strings a whole-step high, and play “like a country

fiddler,” creating a

deliberately shrill effect.) This

brilliantly-orchestrated movement is a series

of contrasts between the slightly macabre music of the

scherzo and contrasting

episodes of lighter character.

Mahler’s original title for the

second movement was Freund Hein spielt

auf (“Friend Hein

plays”). Hein, a figure from Austrian folktales, was a

demonic fiddler who led

people into Hell with his playing. Also in the

background of this deliberately

spooky movement is a self-portrait by the Romantic

painter Arnold Böcklin, a

picture that shows the artist listening as the figure of

Death fiddles just

behind his shoulder. True to the subject-matter, much of

the scherzo is carried

by fiddling from a solo violin. (Mahler directs that the

violinist tune all

strings a whole-step high, and play “like a country

fiddler,” creating a

deliberately shrill effect.) This

brilliantly-orchestrated movement is a series

of contrasts between the slightly macabre music of the

scherzo and contrasting

episodes of lighter character.

In comparing the second and third

movements, Mahler wrote: “The

scherzo is so uncanny, almost sinister, that your hair

may stand on end. Yet in

the following Adagio,

where all

complications are dissolved, you will feel that it

really wasn’t all that

sinister...” This quiet and serene movement is a pair of

interlocked

theme-and-variations forms, one dominated by string

sonorities and the other by

woodwinds. The movement explodes briefly with trumpets

and horns at the end,

but is quickly hushed. The

fourth

movement follows after a brief pause.

The culmination of this work,

Mahler’s setting of Das himmlische

Leben, is simplicity

itself. The stanzas of the poem are set in an

uncomplicated strophic form: essentially

the same music with some variation for each stanza of

poetry. This poem seems

to call for a very direct setting, with its innocent

images of a heaven

populated by friendly saints, where the tables are

overflowing with the best

food (a Romantic German take on The Big

Rock Candy Mountain!), and where heavenly music

resounds. The movement

begins with a clarinet solo, which introduces the tune

sung by the soprano. After

the opening stanzas, the orchestra enters with a

frantic-sounding version of

the first movement’s motto. The next stanzas, dealing

with the death of St.

John’s “little lamb” (Christ), are set in a minor key

and again set off by a

statement of the motto. Major tonality returns again for

the stanzas detailing

the heavenly feast, which are punctuated by woodwind

motives. After a brief

moment the motto returns, but the orchestra continues

with a quiet passage that

leads into the final stanzas, now in a luminous E

Major—this serene mood

remains until the final chord quietly dies away.

________