Madison

Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

May

5-6-7, 2023

97th

Season / Subscription Program 8

This concert

opens with the Symphony

No. 3 by Florence Price. Price’s

music has undergone a revival across the country

recently, and this is the first performance of one of

her works by the Madison Symphony Orchestra. The

orchestra is then joined by soprano Jeni Houser, tenor

Justin Kroll, baritone Ben Edquist, Madison Youth

choirs, and the Madison Symphony Chorus for Carl

Orff’s Carmina

Burana, a powerful setting of texts from

medieval Germany.

Florence Price,

an American composer whose music has undergone a

renaissance in recent years, composed her Symphony No. 3

in the late 1930s. Like much of her music, this work

subtly references various styles of traditional Black

music.

Florence Price,

an American composer whose music has undergone a

renaissance in recent years, composed her Symphony No. 3

in the late 1930s. Like much of her music, this work

subtly references various styles of traditional Black

music.

Florence

Price

Born: April 9,

1888*, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Died: June 3,

1953, Chicago, Illinois.

*

Note: Price's birth year is usually given as 1887.

However, evidence to be laid out in a forthcoming

biography by Samantha Ege and Douglas Shadle shows

that it was actually a year later.

Symphony No. 3

in C minor

-

Composed: 1938-40.

-

Premiere: November 6, 1940, by the Detroit Civic Orchestra, Valter Poole conducting.

-

Previous MSO Performances: This is our first performance of the work.

-

Duration: 30:00.

Background

Price struggled for recognition, even

after her Symphony

No. 1 was performed by the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra in 1933.

Like many of her works, the Symphony No. 3

was performed during her lifetime, but then largely

forgotten until it was finally performed again and

published decades after her death.

Florence Price was born Florence

Smith in Little Rock, into a well-respected family. (Her

father was the only African American dentist in this

strictly segregated city.) She was able to study at the

New England Conservatory of Music, graduating in 1906.

Though the conservatory apparently did accept Black

students at the time, Price initially enrolled as a

“Mexican.” She taught for several years in Atlanta and

Little Rock, but following a lynching in Little Rock in

1927, her family resettled in Chicago, where she would

spend the rest of her life. It was in

Chicago that Price finally began to have success as a

composer. However, she struggled financially,

particularly after she divorced her abusive husband in

1931, leaving her single mother to two daughters. Price

wrote advertising jingles and popular songs under a pen

name and played organ in silent movie theaters to pay

the bills, but her classical compositions began to

attract attention. This culminated in 1933, when her Symphony No. 1

was performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra—the

first composition by a Black woman to be played by a

major orchestra. Though

her music continued to be played and championed by star

performers like Marian Anderson, she struggled to make

ends meet throughout her life. In 1943 she

wrote to Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Serge

Koussevitsky that: “I have two handicaps. I am a woman

and I have some Negro blood in my veins.”

Price’s music was not entirely

forgotten after her death, but much of it was simply

lost. This

changed in 2009, when 30 boxes of her papers and scores

were discovered in a derelict, unoccupied house in St.

Anne, Illinois. (This had been Price’s summer cottage,

but was apparently abandoned after her death.) This

collection included some 200 pieces, including many

previously lost works: two violin concertos, her Symphony No. 4,

and several other scores. This has sparked a tremendous

renewal of interest in her music in the last dozen

years, with many performances and recordings, and

newly-available published editions of her works.

The Depression-era Works Progress

Administration, designed to provide employment for

millions of jobless Americans, is of course best

remembered for its enormous public works projects, its

work in state and national parks, and other

infrastructure construction. However, the WPA also

provided support to musicians through its Federal Music

Project. (In

Madison, for example, the FMP-sponsored Madison Concert

Orchestra gave dozens of radio concerts and free

concerts in the city’s schools and parks in the late

1930s.) The FMP also provided funding to composers, and

Price’s Symphony

No. 3 was one of its commissions. She composed

the work in 1938, and made several revisions in 1940,

before its premiere by the FMP-sponsored Detroit Civic

Orchestra. The performance was a success, but despite

very positive reviews and even an enthusiastic mention

of the piece in first lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s

nationally-syndicated newspaper column, the symphony was

not performed again until 2001 and was finally published

in 2008.

What You’ll Hear

The symphony is in four movements:

• A traditionally-organized opening, with a

slow introduction and which then develops two

contrasting ideas.

• A serene slow movement.

• A fast-paced movement based upon a

traditional Black dance of African origin.

• A turbulent finale.

In writing

about the Symphony

No.3, Price said that it “is intended

to be Negroid in character and expression. In it no

attempt, however, has been made to project Negro music

solely in the purely traditional manner. None of the

themes are adaptations or derivations of folk songs.

The intention behind the writing of this work was a

not too deliberate attempt to picture a cross-section

of present-day Negro life and thought with its

heritage of that which is past, paralleled, or

influenced by concepts of the present day.” Her subtle

references to Black music begin in the opening bars (Andante), a

brass chorale with just a tiny tinge of the Blues. The body of

the movement (Allegro)

is in a Classical sonata form, developing two main

ideas, a restless main theme, and a lush second theme

introduced by horns and trumpets in the style of a

Black spiritual. Price develops both ideas

extensively, often combining fragments of both before

returning to both themes in the recapitulation. A

brief flourish from the harp begins a long coda which

recalls the opening chorale.

The second

movement (Andante

con moto) is peaceful and meditative: with a

lush opening idea leading into a soulful bassoon solo.

The opening melody is developed in the middle,

eventually in a sumptuous statement by full orchestra. Some

elements of the bassoon melody return in the last

passage, but the end of the movement is dominated by

the placid main theme.

Juba, the title

of the third movement, refers to a traditional African

American dance with roots extending back to Africa. The Juba is

a lively dance usually accompanied by body percussion:

claps, stops, and slaps against knees, arms, belly,

chest, and cheeks, often known as “hambone.” (Hambone

originated at a time when enslaved Africans were

forbidden to make or play drums.) Price refers to the

Juba in a few of her works, and here it is heard in

the jaunty, syncopated texture of the opening. The

middle section has a more relaxed feel, with sensuous

solo lines, before the Juba dance returns briefly to

end the movement.

The last

movement (Scherzo:

Finale) begins with a nervous main idea that

comes in waves. This

is developed with some startling harmonic twists, in

an unrelenting intense texture. A

clarinet/bassoon duet brings the swirling motion to a

halt, but only briefly, before it ends with a fierce

coda and stern brass chords.

Carl Orff’s

best-known work, the cantata Carmina Burana,

sets a collection of colorful late medieval texts.

Carl Orff’s

best-known work, the cantata Carmina Burana,

sets a collection of colorful late medieval texts.

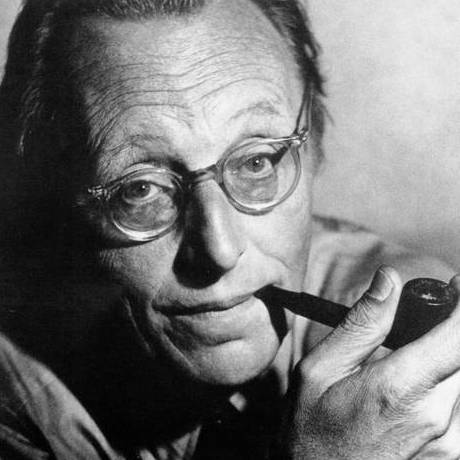

Carl

Orff

Born: July 10,

1895, Munich, Germany.

Died: March

29, 1982, Munich, Germany.

Carmina

Burana

Composed:

1935-36.

Premiere: June 8, 1937 in a staged

production by the Frankfurt Opera, in Frankfurt,

Germany.

Previous MSO

Performances: 1956, 1968, 1989, 1998, 2007, and

2016.

Duration:

59:00.

Background

Carmina

Burana, composed in Nazi Germany, reflects an

idealized view of medieval life.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, a

tremendous body of Latin and vernacular poetry was

created by poets collectively known as “goliards.” To

group them together under a single name is a bit

misleading, however, for the goliards were drawn from

every rank of society. The poets include prominent

churchmen such as Walter of Châtillon (1135-1176) and

Philip, Chancellor of the University of Paris (d.1236),

as well as now-nameless monks, students, vagabonds, and

minstrels. The poetry is just as variable: there are

moralistic and fervidly religious poems, as well as

secular lyrics that range from love songs (including

worshipful courtly love lyrics, bawdy love songs, and

frankly homosexual poetry) to humorous stories and

raucous drinking songs. The most famous collection of

goliard poetry is the Carmina Burana

(literally “Songs of Beuren”), a 13th-century collection

of over 200 poems that was compiled at the Benedictine

monastery in Benediktbeueren, south of Orff’s hometown,

Munich. This richly-illuminated manuscript was probably

compiled for a wealthy abbot of the monastery. Most of

its poems are written in Church Latin, but there are

several poems in a Bavarian dialect of medieval German,

and a few poems that are partially in French (for

example, No. 16 in Orff’s setting).

Carl Orff’s “secular cantata” on

texts from the Carmina

Burana is certainly his best-known work. Orff is a

familiar name to many music educators—he was the creator

of a systematic method of music education for children,

and the composer of an important body of Schulwerke,

educational music. He enjoyed success as a composer in

Germany, but aside from Carmina Burana,

few of his concert or stage works are heard in this

country.

The part of Orff’s biography that is

most fraught with controversy is his relationship with

the Nazis. Unlike German contemporaries like Schoenberg,

Hindemith, and many others who fled the Nazi regime,

Orff remained in Germany and thrived as a composer

throughout the late 1930s and the war years. The

spurious claim that he himself was a Nazi has been

raised more than once. The stridently modernist music he

had composed in the 1920s and early 1930s, and his close

association with many leftists had, in fact, marked him

as “dangerous” to the Nazis. Carmina Burana,

composed in 1935-36, is the earliest of Orff’s

acknowledged works—in 1937, he withdrew from publication

everything else he had composed up to that time. He also

seems to have suppressed any evidence of his previous

ties with leftists and Communists. For example, he

carefully soft-pedaled his collaboration with playwright

Bertholt Brecht in the 1920s and early 1930s. As

detailed in 2000 article by Kim Kowalke, Orff had

assisted Brecht in several productions, and clearly

considered Brecht a mentor. But in 1933, Brecht fled

Germany and his works were considered suspicious. Carmina Burana

represents a fairly new and simpler musical style that

was perfectly in keeping with Nazi cultural policies

promoting music that was uplifting and celebrated the

spirit of the German Volk. Its texts were also in accord with

the idealized view of medieval Germany promulgated by

the Nazi Party. Most controversial of all, Orff agreed

to compose a set of incidental pieces for a 1939

production of A

Midsummer Night’s Dream in Frankfurt: music

intended by the cultural authorities to replace the

standard incidental pieces by the Jewish-born Felix

Mendelssohn. (Orff later regretted this decision.) What

most of Orff’s biographers agree upon is that, if he was

guilty of anything during the Nazi regime, it was that

he had a good sense of the cultural climate and

successfully promoted himself. There is, however, no

good evidence that Orff or any of his close associates

ever actually became members of the Nazi Party, or

subscribed to its ideology.

In speaking about his aesthetic

philosophy, Orff remarked that: “I am often asked why I

nearly always select old material, fairy tales, and

legends for my stage works. I do not see this material

as old, but rather as valid. The time element

disappears, and only the spiritual element remains. My

entire interest is in the expression of these spiritual

realities. I write for the theater to convey a spiritual

attitude.” This sensitivity to the underlying nature of

the texts is clearly apparent in Carmina Burana.

Orff’s choice of poems—all thoroughly secular—and his

ordering of these texts reflects his understanding of

the medieval spirit.

The 25 movements of Carmina Burana

are divided into three large sections, devoted

respectively to springtime, drinking, and love (of all

kinds). As a prologue and epilogue, Orff uses a text

saluting the goddess Fortune, a symbol of the

changeability and fickle nature of luck.

The musical style of Carmina Burana

and much of Orff’s later work owes a great deal to the

neoclassical music of Stravinsky, and echoes of

Stravinsky’s Symphony

of Psalms and Les Noces are

clear. Orff’s style is harmonically simple, with

ostinato rhythmic figures repeated over long static

harmonies—the entire choral prologue, for example, is

set above an unchanging D in the bass. The orchestration

is simple, yet colorful: Orff shows a preference for

percussive effects that highlight the accents of the

text and his own rhythmic figures. Melodic figures are

short and frequently repeated, with very little

development. There are also moments of pure Romanticism,

however, particularly in the baritone’s solo lines. The

melodic material used in Carmina Burana

is, without exception, Orff’s own: he did not use any of

the relatively few extant melodies preserved with

goliard poetry. His original settings of these

700-year-old lyrics are imbued with both freshness and

mystery.

The

texts are arranged into three large sections: I. Spring, II. In the Tavern,

and III. The

Court of Love, and each of these sections is

further divided. The first two texts, serving as a

prelude to Section I, deal with the most potent symbol

of medieval life: the Wheel of Fortune. In countless

manuscript illuminations, including a prominent page in

the original Carmina

Burana manuscript (shown here), the wheel is shown

being manipulated by a capricious Lady Fortune, who

raises and lowers the kings, churchmen, and peasants who

cling to it. Section I, Spring,

reflects an idealized and mythological view of Nature

and Springtime. Spring was an important medieval

metaphor—both for resurrection and for youth—but here

the enjoyment of the season is purely sensuous. In a

subsection, titled On the Green

(Nos. 6-10), the outdoor spirit is directed towards

thoughts of love and dancing. This subsection contains

the only purely orchestral music in Carmina Burana:

an instrumental Tanz

that opens the section, and a Reie

(round-dance) inserted before the chorus Swaz hie gat umbe.

The four numbers set in the tavern give four different

perspectives of medieval merrymaking: drunken musings,

feasting (sung from the perspective of the “feastee,” a

roasted swan!), a satire of a drunken clergyman (who

invokes the spurious St. Decius, patron saint of

gamblers), and finally the drunken and entirely

democratic free-for-all of In taberna quando

sumus. The third and longest section, “Court of

Love,” reflects the twofold conception of love common in

medieval thought. There is both the lofty ideal of

courtly love—chaste longing for an unattainable lady

heard in Dies,

nox et omnia—and openly erotic love in Si puer cum

puellula. In most of the texts, these two threads

are cunningly woven together. This section ends with Blanchefleur and

Helen (No. 24), a single poem, praising Venus in

the same terms often reserved for addresses to the

Virgin Mary. A repeat of the opening chorus, O Fortuna,

serves as a postlude. In returning, Orff neatly

encircles Carmina

Burana within Fortune’s Wheel.

The

texts are arranged into three large sections: I. Spring, II. In the Tavern,

and III. The

Court of Love, and each of these sections is

further divided. The first two texts, serving as a

prelude to Section I, deal with the most potent symbol

of medieval life: the Wheel of Fortune. In countless

manuscript illuminations, including a prominent page in

the original Carmina

Burana manuscript (shown here), the wheel is shown

being manipulated by a capricious Lady Fortune, who

raises and lowers the kings, churchmen, and peasants who

cling to it. Section I, Spring,

reflects an idealized and mythological view of Nature

and Springtime. Spring was an important medieval

metaphor—both for resurrection and for youth—but here

the enjoyment of the season is purely sensuous. In a

subsection, titled On the Green

(Nos. 6-10), the outdoor spirit is directed towards

thoughts of love and dancing. This subsection contains

the only purely orchestral music in Carmina Burana:

an instrumental Tanz

that opens the section, and a Reie

(round-dance) inserted before the chorus Swaz hie gat umbe.

The four numbers set in the tavern give four different

perspectives of medieval merrymaking: drunken musings,

feasting (sung from the perspective of the “feastee,” a

roasted swan!), a satire of a drunken clergyman (who

invokes the spurious St. Decius, patron saint of

gamblers), and finally the drunken and entirely

democratic free-for-all of In taberna quando

sumus. The third and longest section, “Court of

Love,” reflects the twofold conception of love common in

medieval thought. There is both the lofty ideal of

courtly love—chaste longing for an unattainable lady

heard in Dies,

nox et omnia—and openly erotic love in Si puer cum

puellula. In most of the texts, these two threads

are cunningly woven together. This section ends with Blanchefleur and

Helen (No. 24), a single poem, praising Venus in

the same terms often reserved for addresses to the

Virgin Mary. A repeat of the opening chorus, O Fortuna,

serves as a postlude. In returning, Orff neatly

encircles Carmina

Burana within Fortune’s Wheel.

________

program

notes ©2022 by J. Michael Allsen