Madison

Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

April

14-15-16, 2023

J.

Michael Allsen

This program

begins with the evocative Sea Interludes

from Britten’s dark and disturbing opera Peter

Grimes. The dynamic young Canadian violinist Blake

Pouliot played a

memorable performance of the Mendelssohn Violin

Concerto at these concerts in early 2020. Here he

returns to play another

romantic masterwork, the Violin Concerto

No. 3 by Saint-Saëns.

We close with the Symphony

No. 2 by

Brahms—the brightest and most optimistic of his

symphonies.

Peter Grimes, was Britten’s

second opera. He extracted the orchestral Sea

Interludes heard here as the

opera was being prepared for its premiere.

Peter Grimes, was Britten’s

second opera. He extracted the orchestral Sea

Interludes heard here as the

opera was being prepared for its premiere.

Benjamin Britten

Born:

November

22, 1913, Lowestoft, United Kingdom.

Died:

December 4,

1976, Aldeburgh, United Kingdom.

Four Sea Interludes from “Peter

Grimes,” Op. 33a

- Composed:

1944-45.

- Premiere: The

opera Peter

Grimes opened on June 7,

1945 in London. Britten directed the London Philharmonic

Orchestra in the

premiere of the Sea

Interludes less

than a week later, on June 13, 1945 at the Cheltenham

Music Festival.

- Previous MSO

Performances:1970 and 1995.

- Duration: 16:00.

“In

ceaseless motion

comes and goes the tide.

Flowing,

it fills the

channel broad and wide.

Then

back to sea with

strong majestic sweep,

it

rolls in ebb yet

terrible and deep.”

-

Peter Grimes,

close of Act III (after

George Crabbe)

Background

Britten has often been cited as the first

really great English

opera composer since Henry Purcell in the late 17th century.

His dark,

psychological study of the fisherman Peter Grimes is one of

his finest works.

Peter

Grimes,

Britten’s first full-length opera, was a partly product of

the years he spent

in America during World War II. While browsing in a Los

Angeles bookstore in

1941, Britten came across a copy of The

Borough by the English pastor and poet George Crabbe

(1754-1832). Britten was

attracted by this picture of hard life in an English fishing

village, and

particularly drawn to the tragic story of Peter Grimes.

Britten and librettist

Montagu Slater expanded this story into an opera for a

commission by the

Koussevitsky Foundation, and he completed Peter

Grimes in 1945. Since its 1945 premiere, Peter Grimes has been recognized as one of

Britten’s best works,

and it has remained a part of the standard operatic

repertory.

The title character is a bitter,

reclusive fisherman who

lives near The Borough. The villagers suspect that Grimes

may have been

responsible for the death of his apprentice, mistrust that

only increases

Grimes’s isolation. A sympathetic widow, Ellen, and a

retired sailor named

Balstrode try to help him, but he rebuffs Balstrode’s

friendship and ultimately

refuses Ellen’s love. When a second apprentice dies under

suspicious

circumstances, the villagers become a mob, howling for

Grimes’s blood. In what

is certainly one of the most effective “mad scenes” ever

written, Grimes

descends into insanity as the angry crowd approaches. In the

end, Ellen and

Balstrode help Grimes set sail, and he sinks his boat far

out at sea. The

closing words of the opera (given above) are sung by the

inhabitants of The

Borough on the morning after Grime’s suicide, as they

continue life as if

nothing had happened.

It is often said about Britten’s opera Peter Grimes that the chorus is one of the

single most important

“characters” in the drama. Much the same might be said about

the sea, which

provides a constantly-changing background for the entire

story, and, in the

end, it is means of Grimes’s suicide. In describing his

opera, Britten wrote:

“For most of my

life, I have lived

closely in touch with the sea. My parents’ house in

Lowestoft directly faced

the sea, and my life as a child was coloured by the fierce

storms that

sometimes drove ships on to our coast and ate away whole

stretches of

neighbouring cliffs. In writing Peter

Grimes, I wanted to express my awareness of the

perpetual struggle of men

and women whose livelihood depends on the sea...”

What

You’ll Hear

There is a long tradition of depicting the sea

in musical works. Britten’s

Sea Interludes

captures the sea in

four remarkably different moods.

There are six brief orchestral interludes

in Peter Grimes,

one at the beginning of

each act, and one between the two scenes of each act. In Sea Interludes, Britten created a concert

suite from four of these

passages. Dawn

originally appeared

after the opera’s Prologue and before Act I, and paints a

picture of the

seashore at sunrise. You can hear the swirl of waves in the

woodwinds, and low

brass chords evoke the hidden depths of the sea. Near the

end, one great wave

washes the shore before the sea calms again. In Sunday Morning, from the beginning of Act II,

the villagers are

entering church. Horn chords play the part of church bells,

but a chattering

disquiet overlays what should be a tranquil scene.

Alternating with the bell

music is a more lyrical melody, which will be sung by Ellen

as the curtain

rises (“Glitter of waves and glitter of sunlight…”). Moonlight sets the stage for Act III.

Britten’s moonlight glitters

briefly on the sea, but the reigning mood of this section is

brooding and

lonely. The last of the Sea Interludes,

Storm, is drawn

from the middle of

Act I. Gale-force winds are pictured by brass, in violent

competition with the

strings. The tempest Britten has in mind seems not only to

be a storm at sea,

but also the storm in the mind and soul of Grimes.

One of the balances that many 19th-century

composers tried to strike was to compose solo works that had

the virtuoso

thrills demanded by audiences and which also had real

musical substance. This

fine concerto by Saint-Saëns is one of the works that

manages to do both!

One of the balances that many 19th-century

composers tried to strike was to compose solo works that had

the virtuoso

thrills demanded by audiences and which also had real

musical substance. This

fine concerto by Saint-Saëns is one of the works that

manages to do both!

Camille Saint-Saëns

Born:

October 9,

1835, Paris, France.

Died: December 16,

1921, Algiers, Algeria.

Concerto No. 3 in B minor for Violin and

Orchestra, Op. 61

- Composed:

1880.

- Premiere: It is

dedicated to Pablo de Sarasate, who was the soloist in

the premiere in Paris,

on January 2, 1881.

- Previous MSO

Performances: 1927 (Gilbert Ross) and 1996 (Hilary

Hahn).

- Duration:

29:00.

Background

Saint-Saëns had a long

association with

the Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate (1844-1908), and

this concerto is the

most important of the works that came out of their

friendship.

The third

violin concerto by

Saint-Saëns is tied to his long friendship and working

relationship with one of

the 19th century’s greatest violin virtuosos, Pablo de

Sarasate. They met for

the first time when Sarasate was a 15-year-old prodigy and

Saint-Saëns was a

24-year-old composer/organist who already had a formidable

reputation. Sarasate

had always been disappointed by the trivial nature of much

of the virtuoso

music he was called upon to play, and met with Saint-Saëns

to ask for a more

weighty work. In his memoir, Saint-Saëns recalled this first

meeting:

“Flattered and charmed to the highest degree, I promised I

would, and kept my

word with the Concerto in A Major.” This work, composed in

1859 and published

as the Violin

Concerto No.1, was

never a great success, and is only rarely heard today.

However, in 1863

Saint-Saëns composed a second work for his young friend, the

Introduction and Rondo

Capriccioso. This

lightweight, Spanish-flavored showpiece became of the

mainstays of the

19th-century violin repertoire, and was performed countless

times by Sarasate

and other soloists. Their friendship continued as both

Sarasate and Saint-Saëns

matured, and some 17 years later, Saint-Saëns wrote his Violin Concerto No. 3 for his friend. Unlike

his early works for

Sarasate, this concerto is the work of a master composer at

the peak of his

form, and one who knew how to exploit all of the violin’s

capabilities. Saint-Saëns

tells of many pleasant “musical evenings” spent at his home

with Sarasate, and

this experience was put to good use in the Concerto

No.3.

What

You’ll Hear

The concerto is in

three movements:

• An opening

movement, featuring the violin

throughout, develops two contrasting themes.

• A lyrical movement

in the form of a barcarolle,

a gently rocking song in

6/8.

• A third movement

beginning with a dramatic

introduction, and continues as a rondo, dominated by a fiery

main theme.

During the

course of the

opening movement (Allegro

non troppo)

Saint-Saëns was able to use the whole expressive and tonal

range of the violin.

The movement opens with an energetic and passionate theme,

stated in the lowest

range of the violin, and set above quiet string tremolos.

There is a

transitional passage featuring spectacular double and triple

stops from the

soloist and a restatement of the opening theme by full

orchestra. The soloist

then introduces the second main theme, a lovely major-key

melody marked

“sweetly expressive.” The development focuses on the opening

theme, now

overlaid with ornamentation from the violin. The short

recapitulation begins

with the second theme, and closes with a reference to the

first theme, played

as the violin rises to stratospheric heights above the

orchestra.

The second

movement (Andantino

quasi allegretto) is a

dramatic contrast to the first. Its opening theme is a

lilting barcarolle-style

melody, sung by the

violin above sparsely-scored woodwinds, who echo the

violin’s phrases. The

contrasting middle section is also led by the violin. After

restatement of the

opening theme, the movement ends with a wonderful passage in

which Saint-Saëns

displayed both his knowledge of the violin and his mastery

of orchestration.

Here, the violin outlines a series of harmonies in its

highest register, set

against a clarinet playing at the very bottom of its

register, some three

octaves lower. In this ethereal atmosphere, the oboe closes

the movement with a

final statement of the barcarolle.

The closing

movement begins

with an agitated introduction (Molto

moderato e maestoso), a dialogue between the soloist

and orchestra. The

tempo quickens for the main body of the movement (Allegro non troppo), which is constructed as a

rondo, its

reoccurring main theme containing two contrasting ideas: a

brilliant theme

outlined by the violin, which dominates the entire movement,

and a more subdued

transition. The first contrasting section is a much more

lyrical idea, sung

again by the soloist. The central passage is a chorale

melody introduced by

muted strings and later picked up by the violin. This

chorale melody also

reappears, now fleshed out by the brass, in a substantial

coda filled with

virtuoso fireworks.

Brahms composed his

second symphony less than a year after

completing his first, but they have entirely different

characters. The first

was a profoundly serious work in which Brahms was clearly

aware of the

expectations of supporters who had been waiting a long time for him to write a symphony. The

second is much more

relaxed and upbeat, the work of a composer who had proven

himself.

Brahms composed his

second symphony less than a year after

completing his first, but they have entirely different

characters. The first

was a profoundly serious work in which Brahms was clearly

aware of the

expectations of supporters who had been waiting a long time for him to write a symphony. The

second is much more

relaxed and upbeat, the work of a composer who had proven

himself.

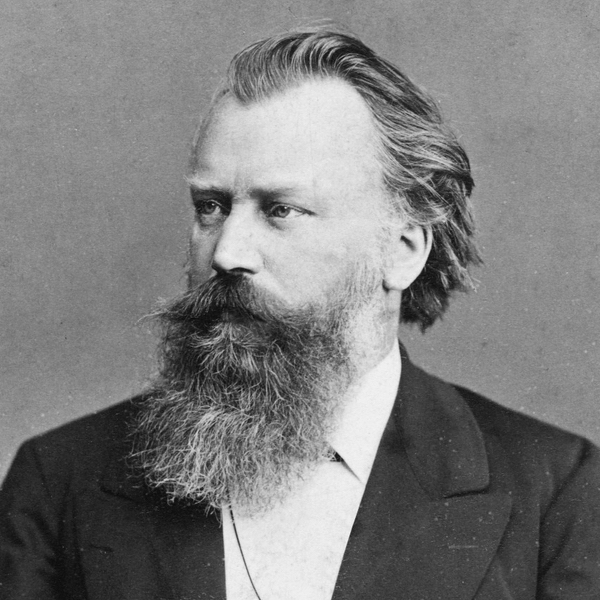

Johannes Brahms

Born:

May 7,

1833, Hamburg, Germany.

Died:

April 3,

1897, Vienna, Austria.

Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op.

73

- Composed: Summer 1877.

- Premiere:

December 30, 1877 by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra,

under the direction of

Hans Richter.

- Previous MSO Performances: 1943, 1956,

1965 1978, 1987, 1997, and

2009.

- Duration: 42:00.

Background

Brahms composed this work with

uncharacteristic speed while he

was spending the summer in a particularly lovely part of

Austria. His

relaxation and the natural beauty clearly seem to come

through in the symphony’s

bright music.

Brahms finished his second symphony

directly on the heels of

his first, but hard to find two symphonies by the same

composer more different

from one another. The first symphony was the result of

almost two decades of

sometimes agonizing composition and recomposition, while the

second was the

work of a single summer holiday spent at his favorite summer

retreat, the

lakeside resort town of Pörtschach in southern Austria. The

Symphony No.2, was

of a much happier and

lighter nature than the Symphony No.1,

and it was an immediate success.

The decade of the 1870s was a generally

happy and productive

period in Brahms’s life. After the premiere of his German Requiem in 1868, his international

reputation was secure,

and honors, commissions, and job offers came in an

ever-increasing stream. The

completion of his Symphony

No. 1 in

1876 marked the end of a long self-imposed apprenticeship in

symphonic

writing—a period of intense study and self-criticism that

had produced works

such as his two orchestral serenades, his first piano

concerto, and the Variations

on a Theme by Haydn. In some

sense, the happy nature of the Symphony

No. 2 must have reflected Brahms’s own happiness over

the end of this

intensely self-critical period. It is occasionally referred

to as his

“Pastoral” symphony: according to his own accounts, Brahms

composed it as a

reaction to the beauty of the countryside surrounding

Pörtschach.

What

You’ll Hear

It is in four movements:

• An opening

movement that spins all of its

material from the music heard in the opening

bars...including a second theme

you are sure to recognize!

• A slow movement

that works with four

distinct musical ideas.

• A scherzo-style

movement linked together by

a Haydnesque country dance.

• A large finale

that develops two contrasting

ideas before ending with a formidable coda.

The opening movement (Allegro

non troppo) of the Symphony No.2

is quiet and peaceful, a horn and woodwind melody above

hushed cellos and

basses. The importance of this introduction goes beyond

setting a mood,

however—the motives of this opening passage are the basis

for all of the

melodic material of the movement. This quiet opening section

gives way to a

flowing melody played by the violins. After a transitional

section, the cellos

and violas play a lovely cantabile

melody that is probably Brahms’s most familiar orchestral

theme. The

development is dense and contrapuntal, building in intensity

until a dissonant

proclamation from the trombones begins a long passage of

harmonic tension. The

recapitulation brings back all of the opening material and

is rounded off with

beautifully lyrical horn solo. The coda ends with a gentle

parody of a Viennese

waltz.

Beneath the calm surface of the second

movement (Adagio non

troppo) lies one of Brahms’s

most complex and original forms. Brahms bases this movement

upon four distinct

groups of melodic material and an exceedingly complicated

harmonic plan. The

opening theme, stated by the cellos, sounds simple enough,

but is notated in

such a way that it is offset from the barlines. (This may

not be apparent to

the listener, but sets up an underlying rhythmic tension.) A

contrasting

episode in 12/8 is set in syncopation above a background of

pizzicato strings.

Another 12/8 theme,

first in the violins, and then in woodwinds and solo horn,

is more placid, but

no less complex. A forceful passage from the full orchestra

introduces new

material, based on the opening theme, and the movement comes

to an understated

conclusion.

The third movement (Allegretto

grazioso) begins with a brief Ländler, an echo of

Austrian country dances

that sounds like a tribute to Haydn. Brahms then gives a nod

to Beethoven in

the scherzo that follows. The Ländler returns again, but is

quickly

overshadowed by more forceful minor-key music. Again, the

texture lightens, now

for a fast-paced new episode. The movement closes with a

densely contrapuntal

passage that fades away after a sustained chord from the

strings.

The finale (Allegro

con spirito) opens quietly, with a subdued theme

stated in the strings and

answered by the bassoon. This theme is subtly related to the

main theme of the

opening movement, tying the entire symphony together. This

hushed opening gives

no hint of what is to follow: a forceful transition section

that develops this

opening theme. A brief clarinet flourish leads into the

second them, a broad

syncopated melody stated by the strings. Near the end of the

development

section, the storm is broken by a brief tranquillo

episode that blends elements of the two main themes. The

recapitulation is cut

short by the trombones, with a dissonant statement of the

second theme’s

syncopated rhythm. The movement concludes with a long and

powerful coda.

________