Click here to

download a "printable" (large-print) version of these

notes.

Madison

Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

December

2-3-4, 2022

97th

Season / Subscription Program 4

J.

Michael Allsen

Welcome to A

Madison Symphony Christmas! As always, this concert is a

rich and varied feast of music for the season, ranging from

serious to lighthearted, and from classical works to popular

holiday favorites. We

welcome a pair of fine vocal soloists: Madison favorite,

mezzo-soprano Adriana Zabala, and baritone Nate

Stampley, a UW–Madison grad and Broadway star. The Madison

Symphony Chorus is joined by two community choirs: groups

from the Madison Youth Choirs and the Mt. Zion Gospel

Choir. We also feature soloists from the orchestra:

flutist Stephanie Jutt, violinist Suzanne Beia, and our

new principal oboist, Izumi Amemiya. And as always, after

a rousing Gospel finale, you get a chance

to join in.

The music

of John Rutter (b.

1945) is nearly always part of our holiday concerts, and

here we begin with his setting of the Christmas hymn that

has the most ancient roots of all, O Come, O Come

Immanuel. This hymn has its origins in the

series of “O antiphons” (O sapientia, O radix Jesse, and several

others) that were chanted as early as the 8th century at

Vespers on the days leading up to Christmas—each one

invoking an aspect of Jesus. In 1851, an English clergyman,

John Mason Neale,

adapted these ancient texts as an English poem, O Come, O Come Emmanuel

and it was then set to the melody of a 15th-century

plainchant hymn, Veni,

Veni Emmanuel. Rutter’s arrangement is straightforward

and effective, beginning with an unadorned version of the

hymn in its beautiful simplicity.

The music

of John Rutter (b.

1945) is nearly always part of our holiday concerts, and

here we begin with his setting of the Christmas hymn that

has the most ancient roots of all, O Come, O Come

Immanuel. This hymn has its origins in the

series of “O antiphons” (O sapientia, O radix Jesse, and several

others) that were chanted as early as the 8th century at

Vespers on the days leading up to Christmas—each one

invoking an aspect of Jesus. In 1851, an English clergyman,

John Mason Neale,

adapted these ancient texts as an English poem, O Come, O Come Emmanuel

and it was then set to the melody of a 15th-century

plainchant hymn, Veni,

Veni Emmanuel. Rutter’s arrangement is straightforward

and effective, beginning with an unadorned version of the

hymn in its beautiful simplicity.

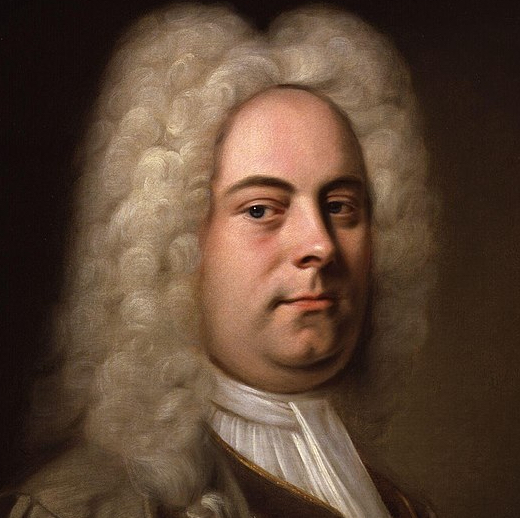

In

1717 George

Friderick Handel (1685-1759) moved to England to

compose and produce opera. For nearly two decades, Handel

was the most successful impresario in England, but by the

1730s, Handel’s Italian opera had gone out of fashion, and

he turned increasingly to the English oratorio. His

oratorios—dramatic renderings of Biblical stories familiar

to his English audiences—were enormously successful, and

their popularity endured and grew long after Handel’s death.

Messiah,

composed in 1741 is, of course, Handel’s most enduring

“hit,” but it is somewhat unusual among his oratorios in

that his text is a pastiche of direct quotes from the St.

James version of the Bible. The chorus For Unto Us a Child

is Born is drawn from Part I, a series of texts

from the New Testament on Christ’s

birth, and Old Testament prophecies—in this case a passage

from the Book of Isaiah. Handel was never shy about

recycling his own music, and in this case, borrowed nearly

of the chorus’s music from an earlier secular cantata. The

striking statements of “Wonderful” and “Counselor” were

created anew for this chorus, however.

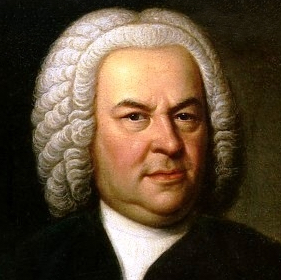

Though Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750) spent

most of career at the Thomaskiche in Leipzig, he seems to

have spent some of the happiest years of his life at the

court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. Bach served as Kapellmeister at

Cöthen from 1717 until he left for Leipzig. Much of his

composition at Cöthen was instrumental: chamber and

orchestra, including most of the famous “Brandenburgs” and

his orchestral suites. The prince maintained a small, but

very skilled orchestra, including several fine soloists. The

Concerto in C minor

for Oboe and Violin, BWV 1060R was among the

works written for the Cöthen orchestra. The violin part

could have been intended for any one of a number of

violinists at the court and the oboe part was probably

written for Bach’s colleague Johann Ludwig Rose, who doubled

as oboist in the orchestra and as the Prince’s private

fencing instructor! No score for the concerto survives, but

in around 1736, Bach rearranged the piece as a concerto for

two harpsicords (BWV 1060). This version was intended for

use by Bach’s Collegium

musicum in Leipzig, a group of amateur and

professional players that Bach directed throughout the

1730s. The editors of the critical edition of Bach’s works

used this keyboard version of the concerto to reconstruct

the original version heard at this concert. Bach’s lyrical

second movement Adagio

is spacious enough to allow the two soloists to fully

express an elegant theme. Their gracefully interweaving

lines are set above a muted string background, until a short

cadenza at the end.

Though Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750) spent

most of career at the Thomaskiche in Leipzig, he seems to

have spent some of the happiest years of his life at the

court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. Bach served as Kapellmeister at

Cöthen from 1717 until he left for Leipzig. Much of his

composition at Cöthen was instrumental: chamber and

orchestra, including most of the famous “Brandenburgs” and

his orchestral suites. The prince maintained a small, but

very skilled orchestra, including several fine soloists. The

Concerto in C minor

for Oboe and Violin, BWV 1060R was among the

works written for the Cöthen orchestra. The violin part

could have been intended for any one of a number of

violinists at the court and the oboe part was probably

written for Bach’s colleague Johann Ludwig Rose, who doubled

as oboist in the orchestra and as the Prince’s private

fencing instructor! No score for the concerto survives, but

in around 1736, Bach rearranged the piece as a concerto for

two harpsicords (BWV 1060). This version was intended for

use by Bach’s Collegium

musicum in Leipzig, a group of amateur and

professional players that Bach directed throughout the

1730s. The editors of the critical edition of Bach’s works

used this keyboard version of the concerto to reconstruct

the original version heard at this concert. Bach’s lyrical

second movement Adagio

is spacious enough to allow the two soloists to fully

express an elegant theme. Their gracefully interweaving

lines are set above a muted string background, until a short

cadenza at the end.

Pietro

Yon (1886-1943) was an organist and church composer.

Born in Italy, Yon emigrated to New York City in 1907, where

he held a series of prestigious posts, eventually serving as

organist at St. Patrick’s cathedral from 1927 until his death.

Yon was admired as a virtuoso performer, and composed dozens

of works for the organ. His catalog of works also includes an

oratorio, nearly two dozen masses, and many smaller choral and

keyboard pieces, but his best-known composition by far is the

Christmas song Gesù Bambino,

composed in 1917. It is heard here in an arrangement for

children’s choir and mezzo-soprano soloist. The next work is a

feature for the younger voices of the Madison Youth Choirs. Mack Wilberg (b.1955), director of the famed Mormon

Tabernacle Choir, wrote his One December Bright

and Clear

in 2001 for treble-voice choir. This work, a setting of

words by David Warner, is a bright, folk-like melody that

breaks joyfully into a round and then into full harmony.

Pietro

Yon (1886-1943) was an organist and church composer.

Born in Italy, Yon emigrated to New York City in 1907, where

he held a series of prestigious posts, eventually serving as

organist at St. Patrick’s cathedral from 1927 until his death.

Yon was admired as a virtuoso performer, and composed dozens

of works for the organ. His catalog of works also includes an

oratorio, nearly two dozen masses, and many smaller choral and

keyboard pieces, but his best-known composition by far is the

Christmas song Gesù Bambino,

composed in 1917. It is heard here in an arrangement for

children’s choir and mezzo-soprano soloist. The next work is a

feature for the younger voices of the Madison Youth Choirs. Mack Wilberg (b.1955), director of the famed Mormon

Tabernacle Choir, wrote his One December Bright

and Clear

in 2001 for treble-voice choir. This work, a setting of

words by David Warner, is a bright, folk-like melody that

breaks joyfully into a round and then into full harmony.

The hymn How Great Thou Art

was originally written in Swedish in 1885, as O store Gud (O Great God) by Carl

Boberg, and it was soon paired with a traditional Swedish

melody. The familiar English lyrics were penned in 1949 by an

English missionary, Stuart K. Hine. This grand arrangement by

Dan Forrest begins with a forceful choral introduction before

the tune enters, working its way to richly-harmonized final

verse.

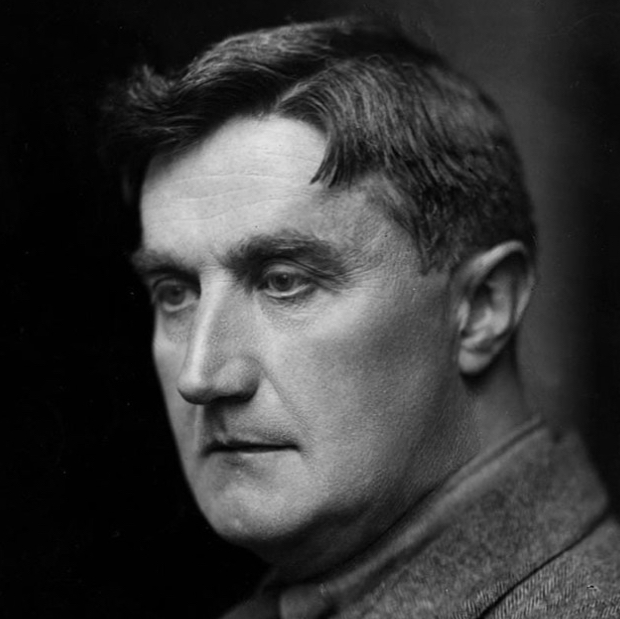

One of the great

ironies in the career of Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) is that this

composer—a professed atheist for much of his life who later

drifted into what his wife described as a “cheerful

agnosticism”—seems so much to have embodied modern English sacred

music. Beginning with his edition of The English Hymnal

(1906), he composed a huge body of hymn tunes, anthems,

Christmas carols, and larger sacred works. In his Magnificat,

he turned to one of the most traditional of liturgical

texts, one of the Biblical canticles (Luke 1: 46-55), sung

here in English. This prayer, in the voice of Mary, is her

response to the Annunciation that she had conceived a child

by the Holy Spirit. The Magnificat was sung

during the Vespers (Evensong) service in both the Catholic

Church and the Church of England. Vaughan Williams’s Magnificat was

composed for the mezzo-soprano Astra Desmond in 1932, and is

among the most innovative settings of this text. He was

careful to place a note in the score that his version “is

not intended for liturgical use”—recognizing that both the

spirit and the form of this work made it unsuitable for the

staid ritual of the church. He wrote to his friend Gustav

Holst that this was an effort to “lift the words out of the

smug atmosphere which had settled on them after being sung

at evening service for so long.” Here we have not merely a

prayer, but a dramatic scene with three characters. While

the soloist sings the canticle, a chorus of women plays the

role of the Angel of the Annunciation, inserting new

Biblical text. A third character appears in the guise of a

solo flute, described by Vaughan Williams as “the

disembodied visiting spirit”—that is, the spirit that enters

Mary’s womb. The choral music of the Angel is ethereal

throughout, while the flute’s line is unabashedly sensuous.

Mary’s part is operatic in both its style and in its breadth

of emotion, from her ecstatic opening phrase to the

power—and even warlike anger—of the line “He hath shewed

strength with his arm.” After a great moment of choral

rapture on “and of his Kingdom there shall be no end,” the

ending is quiet and understated, with a passionate duet

between the soloist and flute, and a hushed prayer by the

chorus.

One of the great

ironies in the career of Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) is that this

composer—a professed atheist for much of his life who later

drifted into what his wife described as a “cheerful

agnosticism”—seems so much to have embodied modern English sacred

music. Beginning with his edition of The English Hymnal

(1906), he composed a huge body of hymn tunes, anthems,

Christmas carols, and larger sacred works. In his Magnificat,

he turned to one of the most traditional of liturgical

texts, one of the Biblical canticles (Luke 1: 46-55), sung

here in English. This prayer, in the voice of Mary, is her

response to the Annunciation that she had conceived a child

by the Holy Spirit. The Magnificat was sung

during the Vespers (Evensong) service in both the Catholic

Church and the Church of England. Vaughan Williams’s Magnificat was

composed for the mezzo-soprano Astra Desmond in 1932, and is

among the most innovative settings of this text. He was

careful to place a note in the score that his version “is

not intended for liturgical use”—recognizing that both the

spirit and the form of this work made it unsuitable for the

staid ritual of the church. He wrote to his friend Gustav

Holst that this was an effort to “lift the words out of the

smug atmosphere which had settled on them after being sung

at evening service for so long.” Here we have not merely a

prayer, but a dramatic scene with three characters. While

the soloist sings the canticle, a chorus of women plays the

role of the Angel of the Annunciation, inserting new

Biblical text. A third character appears in the guise of a

solo flute, described by Vaughan Williams as “the

disembodied visiting spirit”—that is, the spirit that enters

Mary’s womb. The choral music of the Angel is ethereal

throughout, while the flute’s line is unabashedly sensuous.

Mary’s part is operatic in both its style and in its breadth

of emotion, from her ecstatic opening phrase to the

power—and even warlike anger—of the line “He hath shewed

strength with his arm.” After a great moment of choral

rapture on “and of his Kingdom there shall be no end,” the

ending is quiet and understated, with a passionate duet

between the soloist and flute, and a hushed prayer by the

chorus.

Though Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

has most often been represented in Overture Hall by his

orchestral works, he was also a prolific and sensitive choral

composer throughout his career. Some of his choral

works—particularly his great settings of Latin sacred texts:

the Stabat Mater, Te Deum, Requiem, and the Mass in D Major—were

tremendously popular in their time, and remain in the choral

repertoire today. The Mass in D Major is

his only surviving setting of the Latin Mass: he wrote and

discarded a pair of masses as a young man, while still

studying at the Prague Organ School, but the Mass in D Major was a

mature work written by an accomplished and, by then,

world-famous composer. Dvořák composed it in 1887 at the

request of a wealthy Czech architect and patron, Josef Hlávka, for the

consecration of a private chapel on Hlávka’s estate. This

initial version was a small-scale work that reflected the

resources Hlávka could provide: soloists, chorus, and organ.

Dvořák’s

London publisher Novello, published the work, but Novello

almost immediately asked for a larger version. The version

heard here, with orchestral accompaniment was completed in

1893, and was premiered in London on March 11 of that year.

The choral Gloria

movement heard here sets the standard Latin text from the

Mass. It begins with a—well—glorious choral fanfare on the ecstatic

opening words. Dvořák’s setting heightens the

changing meaning of the text, with a fugue leading to a more

prayerful middle section with a simple organ accompaniment.

This gradually leads to more exalted music and a rousing

fugal coda on the words Cum sancto spiritu.

As

always, we return to Handel’s Messiah for the finale

to our first half: the

concluding Hallelujah

chorus from Part II. This chorus,

undoubtedly the single most famous work by Handel, has been

a sensation since the first performance of Messiah in Dublin

in 1742. 50 years later, while on tour in England, Joseph Haydn heard a festival performance of Messiah in May of

1791, and was profoundly moved: bursting into tears during

the Hallelujah

chorus. (The experience was a primary inspiration for

his own great oratorio, The Creation, of

1798.) The chorus is heard today in contexts that

Handel—tireless self-promoter though he was—never dreamed

of: movies, TV ads and sitcoms, and in cover versions in

styles ranging from gospel and jazz to rock, punk, and rap.

The music is in no danger of becoming a mere cliché,

however: it remains true to Handel’s original intent.

Following the first performance of Messiah in London,

the composer remarked: “My Lord, I should be sorry if I only

entertained them. I wished to make them better.”

As

always, we return to Handel’s Messiah for the finale

to our first half: the

concluding Hallelujah

chorus from Part II. This chorus,

undoubtedly the single most famous work by Handel, has been

a sensation since the first performance of Messiah in Dublin

in 1742. 50 years later, while on tour in England, Joseph Haydn heard a festival performance of Messiah in May of

1791, and was profoundly moved: bursting into tears during

the Hallelujah

chorus. (The experience was a primary inspiration for

his own great oratorio, The Creation, of

1798.) The chorus is heard today in contexts that

Handel—tireless self-promoter though he was—never dreamed

of: movies, TV ads and sitcoms, and in cover versions in

styles ranging from gospel and jazz to rock, punk, and rap.

The music is in no danger of becoming a mere cliché,

however: it remains true to Handel’s original intent.

Following the first performance of Messiah in London,

the composer remarked: “My Lord, I should be sorry if I only

entertained them. I wished to make them better.”

Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov

(1844-1908) completed The Snow Maiden (Snegorouchka) in

1881—one of innumerable Romantic operas based upon fairy

tales. It retells the story from Russian folklore—by way of a

popular 1873 play—of the love of the young fairy princess, the

Snow Maiden, who has been raised by mortals, for a young man

of her village. This kind of fairy tale rarely ends “happily

ever after,” and this one is no exception, as both the Snow

Maiden and her lover die in the end. However, though it is a

tragedy, The Snow

Maiden includes some of Rimsky-Korsakov’s finest

operatic writing, and it apparently remained one his personal

favorites among his own works. There is nothing tragic about

the opera’s Dance of the Tumblers,

which opens our second half. This energetic and bumptious

music opens Act III of the opera, where the villagers are

throwing a wild party in celebration of the visiting Tsar.

John

Rutter is

celebrated as both a choral conductor and as a composer of

choral works, from small anthems to settings of the Gloria, Magnificat, and Requiem. Rutter has

explained that Christmas music has “…always occupied a

special place in my affections, ever since I sang in my

first Christmas Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols as a

nervous ten-year-old boy soprano. For me, and I suspect for

most of the other members of the Highgate Junior School

Choir, it was the high point of our singing year, diligently

rehearsed and eagerly anticipated for weeks beforehand.

Later, my voice changed and I turned from singing to

composition, but I never forgot those early Highgate carol

services.” His Angel Tidings,

published in 1969, was based upon a Moravian carol, though

the words are Rutter’s own. This is a bright and joyful song

of celebration over the birth of Jesus.

John

Rutter is

celebrated as both a choral conductor and as a composer of

choral works, from small anthems to settings of the Gloria, Magnificat, and Requiem. Rutter has

explained that Christmas music has “…always occupied a

special place in my affections, ever since I sang in my

first Christmas Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols as a

nervous ten-year-old boy soprano. For me, and I suspect for

most of the other members of the Highgate Junior School

Choir, it was the high point of our singing year, diligently

rehearsed and eagerly anticipated for weeks beforehand.

Later, my voice changed and I turned from singing to

composition, but I never forgot those early Highgate carol

services.” His Angel Tidings,

published in 1969, was based upon a Moravian carol, though

the words are Rutter’s own. This is a bright and joyful song

of celebration over the birth of Jesus.

The hymn Come Thou Fount of

Every Blessing was written in 1758 by the British

pastor Robert Robinson. In the United States, this hymn was

paired with an anonymous tune known as Nettleton. This had

first appeared in 1813 in a “shape-note” collection titled Wyeth’s Repository of

Sacred Music. (Shape-note music, in which noteheads are

printed in different shapes corresponding to solfege

syllables, was a distinctly American tradition created in the

late 18th century. Like Nettleton,

many of these tunes have a rustic, sturdy beauty.) This

arrangement by Mack Wilberg opens simply with an a capella verse by

the women that replicates the simple spirit of the original,

moving gradually towards a lushly-orchestrated conclusion.

Our next two works are Christmas

songs in Spanish, in arrangements created especially for

this concert by local composer Scott Gendel. Los peces en

el rio—a familiar favorite in the

Spanish-speaking world—is an anonymous song from Spain. It

is a villancico, a form from the

Middle Ages, and the song itself is ancient, possibly dating

from as early as the 13th century. Its verses describe the

beauty and gentleness of the Virgin Mary and the poverty of

her baby boy, but its refrain is a joyful reminder that the

entire earth celebrated the birth of the Baby Jesus, even

the fish in the river. The line “Beben y beben y vuelven a

bebe” (They drink and drink, and drink again) is probably

meant to evoke an image of the fish chattering excitedly to

one another. According to Gendel, Adriana Zabala, for whom

this arrangement was created, describes this song as a kind

of “anti-Silent Night.” That is, that the birth of

Jesus is not met by quiet and calm but by noisy joy! A la nanita

nana was arranged as a duet for both of our

vocal soloists. This

song was published in 1904 by the Spanish songwriter José Ramón Gomis

(1856-1939). It

was written as a tender lullaby, with the kind of soothing,

murmuring refrain heard in lullabies of every culture.

Gendel injects a gentle dance feel into this setting,

reflecting, as he says, the “swaying

and dancing of a mother rocking a child.”

Our next two works are Christmas

songs in Spanish, in arrangements created especially for

this concert by local composer Scott Gendel. Los peces en

el rio—a familiar favorite in the

Spanish-speaking world—is an anonymous song from Spain. It

is a villancico, a form from the

Middle Ages, and the song itself is ancient, possibly dating

from as early as the 13th century. Its verses describe the

beauty and gentleness of the Virgin Mary and the poverty of

her baby boy, but its refrain is a joyful reminder that the

entire earth celebrated the birth of the Baby Jesus, even

the fish in the river. The line “Beben y beben y vuelven a

bebe” (They drink and drink, and drink again) is probably

meant to evoke an image of the fish chattering excitedly to

one another. According to Gendel, Adriana Zabala, for whom

this arrangement was created, describes this song as a kind

of “anti-Silent Night.” That is, that the birth of

Jesus is not met by quiet and calm but by noisy joy! A la nanita

nana was arranged as a duet for both of our

vocal soloists. This

song was published in 1904 by the Spanish songwriter José Ramón Gomis

(1856-1939). It

was written as a tender lullaby, with the kind of soothing,

murmuring refrain heard in lullabies of every culture.

Gendel injects a gentle dance feel into this setting,

reflecting, as he says, the “swaying

and dancing of a mother rocking a child.”

We continue with

features for our vocal soloists. The Sound of Music

was the eighth and final collaboration of composer Richard Rodgers and

lyricist Oscar

Hammerstein II. Beginning with Oklahoma! in 1943,

they created a series of phenomenally successful musicals that

ruled the Broadway stage, most of them becoming equally

successful Hollywood movies. The Sound of Music, a fictionalized version of

the story of the von Trapp Family singers, was a smash hit on

Broadway when it opened in 1959, running for some 1443

performances. The 1965 movie version was every bit as big a

hit, becoming one of the highest-grossing films of all time. My Favorite Things

is feature for Maria, the high-spirited governess of the von

Trapp children—sung by Mary Martin on Broadway and by Julie

Andrews on film. It is a quirky list of those things that she

thinks about to cheer herself up whenever it’s needed. Winter Wonderland

was one of many cheerful holiday songs that came out of the

Great Depression. It was a 1934 collaboration by lyricist Richard Smith and

composer Felix Bernard,

and was a No.2 hit that year for the Guy Lombardo orchestra.

The song, with its cozy, sentimental imagery of snowmen and

cold winter walks—and warming by the fire afterwards—had

tremendous staying power and was a hit for both Perry Como and

the Andrews Sisters in the 1940s. Since then, it’s never left

the list of holiday standards.

We continue with

features for our vocal soloists. The Sound of Music

was the eighth and final collaboration of composer Richard Rodgers and

lyricist Oscar

Hammerstein II. Beginning with Oklahoma! in 1943,

they created a series of phenomenally successful musicals that

ruled the Broadway stage, most of them becoming equally

successful Hollywood movies. The Sound of Music, a fictionalized version of

the story of the von Trapp Family singers, was a smash hit on

Broadway when it opened in 1959, running for some 1443

performances. The 1965 movie version was every bit as big a

hit, becoming one of the highest-grossing films of all time. My Favorite Things

is feature for Maria, the high-spirited governess of the von

Trapp children—sung by Mary Martin on Broadway and by Julie

Andrews on film. It is a quirky list of those things that she

thinks about to cheer herself up whenever it’s needed. Winter Wonderland

was one of many cheerful holiday songs that came out of the

Great Depression. It was a 1934 collaboration by lyricist Richard Smith and

composer Felix Bernard,

and was a No.2 hit that year for the Guy Lombardo orchestra.

The song, with its cozy, sentimental imagery of snowmen and

cold winter walks—and warming by the fire afterwards—had

tremendous staying power and was a hit for both Perry Como and

the Andrews Sisters in the 1940s. Since then, it’s never left

the list of holiday standards.

Let There Be Peace on

Earth (And Let It Begin With Me) was written by

the husband-wife team of Sy Miller and Jill Jackson, as

they were at a weeklong retreat on a California mountaintop.

Miller later recalled: “One summer evening in 1955,

a group of 180 teenagers of all races and religions, meeting

at a workshop high in the California mountains locked arms,

formed a circle and sang a song of peace. They felt that

singing the song, with its simple basic sentiment—’Let there

be peace on earth and let it begin with me,’ helped to

create a climate for world peace and understanding. When they came

down from the mountain, these inspired young people brought

the song with them and started sharing it...” This

inspirational song has developed an association with the

Christmas season, but its appeal and intent are much

wider—it became, for example a widely-heard anthem of peace

amidst the anger and sadness following the 9/11 attacks.

Once again this year, we are

privileged to welcome the Mount Zion Gospel Choir and its

directors Leotha and Tamera Stanley, presenting gospel songs

for the season arranged for these concerts by Leotha Stanley. Mt.

Zion opens with a new gospel arrangement of Do You Hear What I

Hear? This holiday standard was written in

1962 by composer Noel

Regney and his wife, lyricist Gloria Shayne Baker

wrote the holiday standard Do You Hear What I

Hear? in 1962 and it became a huge hit for Bing

Crosby in 1963, selling over a million records. Though

usually heard as a sentimental song to the Baby Jesus,

Regney later said “I am amazed that people can think they

know the song, and not know it is a prayer for peace.” It

was written in October 1962, at the height of the Cuban

Missile Crisis, when nuclear war seemed imminent. Contrary

to their usual practice, Regney wrote the lyric, and his

wife wrote the melody. The result was a song that they found

so moving that they couldn’t bear to sing it at first. The

final stanza, with its “Pray for peace, people everywhere!”

makes this as relevant in 2022 as it was in 1962. The Mount

Zion group then sings a Stanley original, The Spirit of Christmas

is Love, which was introduced at these concerts in

2014. Our finale, sung by every voice on stage, is a

newly-written song by Stanley, Christmas Bells: The

Message They Ring.

Once again this year, we are

privileged to welcome the Mount Zion Gospel Choir and its

directors Leotha and Tamera Stanley, presenting gospel songs

for the season arranged for these concerts by Leotha Stanley. Mt.

Zion opens with a new gospel arrangement of Do You Hear What I

Hear? This holiday standard was written in

1962 by composer Noel

Regney and his wife, lyricist Gloria Shayne Baker

wrote the holiday standard Do You Hear What I

Hear? in 1962 and it became a huge hit for Bing

Crosby in 1963, selling over a million records. Though

usually heard as a sentimental song to the Baby Jesus,

Regney later said “I am amazed that people can think they

know the song, and not know it is a prayer for peace.” It

was written in October 1962, at the height of the Cuban

Missile Crisis, when nuclear war seemed imminent. Contrary

to their usual practice, Regney wrote the lyric, and his

wife wrote the melody. The result was a song that they found

so moving that they couldn’t bear to sing it at first. The

final stanza, with its “Pray for peace, people everywhere!”

makes this as relevant in 2022 as it was in 1962. The Mount

Zion group then sings a Stanley original, The Spirit of Christmas

is Love, which was introduced at these concerts in

2014. Our finale, sung by every voice on stage, is a

newly-written song by Stanley, Christmas Bells: The

Message They Ring.

And then, friends, it’s your turn to sing...

________

program notes ©2022 by J. Michael Allsen