Click here to

download a "printable" (large-print) version of these

notes.

Madison

Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

November

11-12-13, 2022

97th

Season / Subscription Program 3

J.

Michael Allsen

This program

opens with the lively Danzón No. 2

by

Mexican composer Arturo Márquez, based upon folk dance

from Veracruz. We

then welcome back Madison’s own Christina and Michelle

Naughton. The

Naughtons—twin sisters—were both soloists multiple times

in our youth concerts

when they were growing up in Madison, and they have been

working as a piano duo

since 2010. They first performed as a duo with the

Madison Symphony Orchestra

in 2012, playing Poulenc’s Concerto for

Two Pianos and they returned in 2016 for Mozart’s

two-piano concerto. Here

they play a late romantic work by Max Bruch. We close

with the emotional sixth

symphony of Tchaikovsky, the Russian master’s final

work.

The

Danzón No. 2 of

Arturo

Márquez is his most popular work, and one of the most

frequently-performed pieces of contemporary Mexican

music for orchestra. This

is his colorful adaptation of a Mexican folk dance that

has Afro-Cuban roots.

The

Danzón No. 2 of

Arturo

Márquez is his most popular work, and one of the most

frequently-performed pieces of contemporary Mexican

music for orchestra. This

is his colorful adaptation of a Mexican folk dance that

has Afro-Cuban roots.

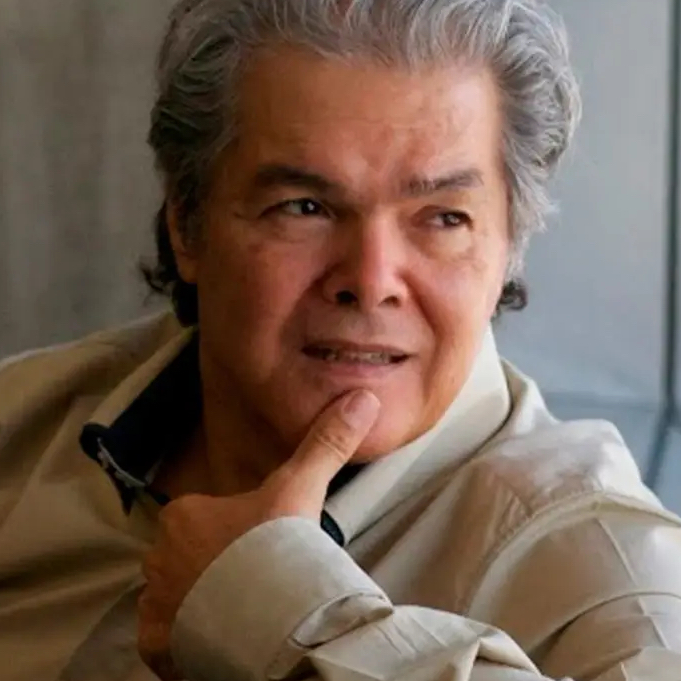

Arturo

Márquez

Born: December

20, 1950, Álamos, Mexico.

Danzón No. 2

- Composed: 1994.

- Premiere: Danzón No. 2

was commissioned by the National

Autonomous University of Mexico. The university’s

symphony orchestra played its

premiere in Mexico City in 1994.

- Previous MSO

Performances: This is our first performance of the

work.

- Duration: 10:00.

Background

Márquez was introduced to

music by his father, who

was a carpenter by day and a mariachi violinist by

night.

Arturo Márquez, one of Mexico’s most

successful contemporary

composers, was born in the state of Sonora. When he was

12 years old, his

family moved to a suburb of Los Angeles, where he

studied piano, violin, and

trombone. Márquez later recalled that “My adolescence was spent

listening to Javier Solis

[the famous Mexican singer/actor], sounds of mariachi,

the Beatles, Doors,

Carlos Santana and Chopin.” He later studied

at the Conservatory of Music

of Mexico, with the great French composer Jacques

Castérède in Paris, and at

the California Institute of the Arts. He is on the

faculty of the National

Autonomous University in Mexico City. Márquez frequently

uses Mexican and other

Latin folk influences in his works, and his best-known

series of works are the Danzónes he

began composing in the 1990s

for orchestra and other ensembles. The danzón

is a dance of Cuban origins, and early Cuban danzónes in the 19th century combined

intricate European-style figure

dancing with African-derived rhythms, and the form is in

the background of many

later Caribbean styles. The danzón

was particularly popular in the Mexican state of

Veracruz, where it remains one

of the primary forms of folkloric music. Like nearly all

Caribbean dance forms

it is first and foremost a rhythm: in this case, the

insistent five-beat

pattern known as clave:

the same

rhythm that provides the “heartbeat’ of rumba, son, and

salsa music.

What You’ll Hear

The clave rhythm that underlies this work is a

legacy of the African

Diaspora: derived from West African drum music, it was

brought to the Caribbean

by enslaved Africans.

The clave appears

in the opening bars of Danzón No.2,

supporting a sinuous solo for the clarinet, eventually

joined by the oboe. The

intensity ratchets up as more instruments enter, but the

clave is always calmly in the background.

There is a brief hushed

interlude for piano and solo violin that recalls the

old-fashioned sound of

19th-century danzónes,

and this is

given a more lush treatment by the strings. There is a

sudden break and a new

character, more intense and brassy, though the tempo and

clave rhythm stay immovable until the

brash ending.

This

late work by Bruch was not heard in its original form

until over 60

years after was written. And there’s an interesting story

behind that...

This

late work by Bruch was not heard in its original form

until over 60

years after was written. And there’s an interesting story

behind that...

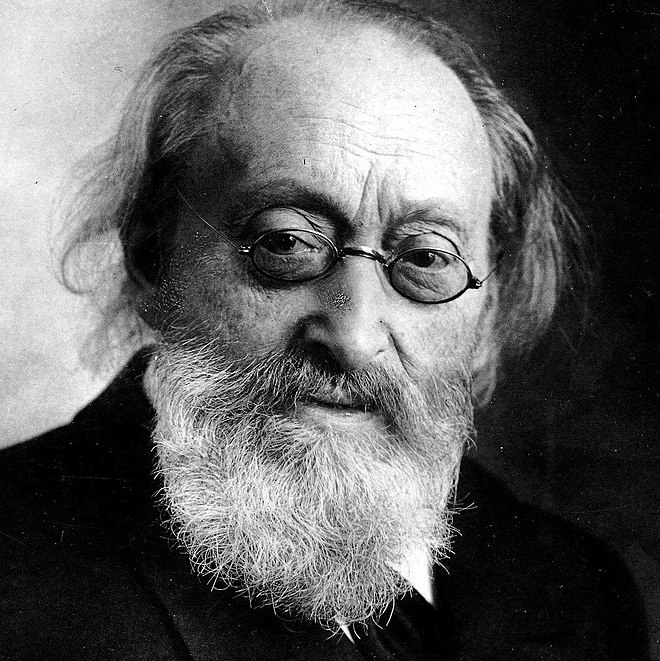

Max Bruch

Born:

January 6, 1838, Cologne,

Germany.

Died:

October 2, 1920, Friedenau (near

Berlin), Germany.

Concerto for Two

Pianos and Orchestra in A-flat minor, Op. 88a

- Composed: 1912.

-

Premiere: The

work was performed, in a simplified version, by sisters

Rose and Otilie Sutro,

with the Philadephia Orchestra, directed by Leopold

Stokowski, on December 29,

1916. Bruch’s original version was finally recorded in

1973, by pianists Nathan

Twining, and Martin Berkovsky, who performed with the

London Symphony Orchestra

under Antal Dorati.

-

Previous

MSO Performances: This is our first

performance of the work.

-

Duration: 22:00.

Background

Bruch was one

of Germany’s leading composition teachers, and his

students included Dr. Sigfrid

Prager, who would become first conductor of the Madison

Civic Symphony

(predecessor of today’s MSO) in 1926. Prager studied with

Bruch in Berlin in

the years prior to World War I.

Max

Bruch

is known today primarily for two solo violin works,

the Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor and

the Scottish Fantasy, and for his Kol

Nidrei for cello and orchestra. However, Bruch

was a tremendously

successful composer in his day, with a catalog of

nearly a hundred works that

included three operas, three symphonies, five

concertos, dozens of other

orchestral pieces, sacred and secular choral works,

art songs, and chamber

music. He was also a well-regarded conductor and one

of the most sought-after composition

teachers in Europe: Ottorino Respighi and Ralph

Vaughan Williams were among his

more famous pupils. In 1912, when he composed his Concerto for Two Pianos, Bruch was in

his 70s, and had retired

after over 20 years teaching composition at Berlin’s

famed Hochschule (Conservatory)

für Musik. He had actually declared to a friend when

he reached his 70th

birthday in 1908 that he was through with composing.

In fact, he continued to

write music almost until his death at age 82.

Rose and Otilie Sutro

in 1917

The Concerto for Two Pianos has a

fascinating—and rather twisted—story.

In 1911, Bruch heard a performance of his 1861 Fantasy for Two Pianos by the American

duo-pianists Rose and Otilie

Sutro. The Sutro sisters were then touring Europe, and

had known him in the

1890s when they were students at the Berlin

Hochschule. Bruch, flattered by

their request that he write a two-piano concerto for

them, promptly agreed, and

in 1912, he sent the autograph score to the sisters in

the United States. Bruch’s

concerto was adapted from a

suite for organ and orchestra he had been working on

since 1904. In 1916, the

Sutros performed the “premiere” of the Concerto

for Two Pianos in Philadephia, but unbeknownst

to Bruch, what they played

was a dramatically simplified version. The sisters had

the gall to copyright their

arrangement, and they

continued to tinker with it for the next few decades.

Bruch himself never heard

the work performed, but on the strength of the

supposed premiere, he later

agreed to send the autograph of his by-then famous Violin Concerto No. 1 to the Sutros, who

promised to arrange for

publication in the United States. Not only did they

arrange for Bruch to be

paid in nearly worthless German Marks (their value

destroyed by postwar

inflation), they never returned the manuscript and

later sold it for a hefty

sum in 1949. The original version of Bruch’s Concerto for Two Pianos remained

completely unknown until after

Otilie’s death in 1970 (Rose had died in 1957), when

her papers were auctioned.

Pianist Nathan Twining acquired both the Sutros’

version and Bruch’s original

autograph manuscript. Bruch’s original was finally

performed—over 60 years

after he had composed it—in a 1973 recording by

Twining and pianist Martin

Berkovsky. The concerto was published in 1977 as

Bruch’s Op. 88a.

The Concerto for Two Pianos has a

fascinating—and rather twisted—story.

In 1911, Bruch heard a performance of his 1861 Fantasy for Two Pianos by the American

duo-pianists Rose and Otilie

Sutro. The Sutro sisters were then touring Europe, and

had known him in the

1890s when they were students at the Berlin

Hochschule. Bruch, flattered by

their request that he write a two-piano concerto for

them, promptly agreed, and

in 1912, he sent the autograph score to the sisters in

the United States. Bruch’s

concerto was adapted from a

suite for organ and orchestra he had been working on

since 1904. In 1916, the

Sutros performed the “premiere” of the Concerto

for Two Pianos in Philadephia, but unbeknownst

to Bruch, what they played

was a dramatically simplified version. The sisters had

the gall to copyright their

arrangement, and they

continued to tinker with it for the next few decades.

Bruch himself never heard

the work performed, but on the strength of the

supposed premiere, he later

agreed to send the autograph of his by-then famous Violin Concerto No. 1 to the Sutros, who

promised to arrange for

publication in the United States. Not only did they

arrange for Bruch to be

paid in nearly worthless German Marks (their value

destroyed by postwar

inflation), they never returned the manuscript and

later sold it for a hefty

sum in 1949. The original version of Bruch’s Concerto for Two Pianos remained

completely unknown until after

Otilie’s death in 1970 (Rose had died in 1957), when

her papers were auctioned.

Pianist Nathan Twining acquired both the Sutros’

version and Bruch’s original

autograph manuscript. Bruch’s original was finally

performed—over 60 years

after he had composed it—in a 1973 recording by

Twining and pianist Martin

Berkovsky. The concerto was published in 1977 as

Bruch’s Op. 88a.

What You’ll Hear

This romantic concerto is

laid out in four

movements:

• It opens

with a grand fanfare, and an

extended fugue, both based upon themes Bruch heard on

the Italian island of

Capri.

• A lively

scherzo-style movement with a slow

introduction.

• A lyrical

slow movement.

• A grand

finale, based on the main ideas from

the opening movement.

The

concerto’s origins as a suite for organ and orchestra

may have

been responsible for

its unusual four-movement form. The opening movement (Andante sostenuto) begins with a stern

fanfare, that, according to Bruch,

was derived from a Good Friday procession he heard

while recovering from an

illness on the resort island of Capri in 1904. Bruch

remembered that, leading

the procession

“was

a

messenger of

sadness with a large tuba, on which he played a kind

of signal. It was not bad:

one could make a good funeral march out of it! Next

came several large flowered

crosses, one carried by a hermit from Mount Tiberio.

Then 200 children dressed

in white and carrying large burning candles, each of

them also holding a small

black cross. They saying in unison a kind of

lamentation...”

The

children’s lament, which he transcribed, here became

the subject of a solemn

fugue. The fanfare eventually returns

with

great ferocity, before a calm closing episode from the

pianos.

The second

movement (Andante

con moto) begins

in a

quiet, pastoral mood, an

episode decorated by the pianos, before launching into

lively scherzo-style

music (Allegro

molto vivace). pianos

and orchestra develop a series of new ideas before

returning to the scherzo

theme and a rousing ending. The slow movement (Adagio non troppo) begins with a quiet

introduction, led by solo

horn, before the pianos introduce a flowing main

theme. This eventually grows

into a passionate statement for orchestra. In the

remainder of the movement,

this idea is developed in an unhurried way, rising to

one last grand peak

before a quiet conclusion.

The closing movement (Andante)

begins with a return of the opening fanfare, which is

developed expansively,

before the tempo suddenly quickens (Allegro).

The movement’s main theme is a fierce idea derived

from the fanfare, though

Bruch also introduces a calmer second idea: a version

of the children’s lament

of the opening movement. The short development focuses

on the fanfare, and

after a recapitulation of these ideas, concerto ends

with a fiery coda

dominated by the fanfare.

Tchaikovsky’s

very last work, premiered

just over a week before his death, is profoundly sad

and moving, but also a

work with several brilliantly innovative moments.

Tchaikovsky’s

very last work, premiered

just over a week before his death, is profoundly sad

and moving, but also a

work with several brilliantly innovative moments.

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7,

1840, Votkinsk, Russia.

Died:

November 6,

1893, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Symphony No. 6

in B minor, Op. 74

(“Pathétique”)

-

Composed: Between February and August 1893.

-

Premiere: The Symphony No. 6 was first played in St. Petersburg on October 28, 1893, with Tchaikovsky conducting.

-

Previous MSO Performances: 1945, 1956, 1963, 1971, 1982, 1999, and 2017.

-

Duration: 45:00.

“You can’t

imagine what bliss I feel, being convinced that my

time is not yet passed and I

can still work. Perhaps, of course, I’m mistaken,

but I don’t think so.”

- Tchaikovsky (to his nephew)

Background

Tchaikovsky

was a composer who wore his

heart on his sleeve...and who revealed his heart in

his music. The tragic Symphony No. 6

was a reflection of his

state of mind in the last year of his life.

Tchaikovsky’s

late symphonies are

autobiography of the most revealing kind. This was a

man who felt and suffered

deeply, and those feelings—fear, guilt, insecurity,

and occasionally joy—came

though most clearly in these works. The idea of Fate

figures prominently in the

programs of the fourth and fifth symphonies. The

fourth (1877) seems to be a

titanic battle with Fate, most likely occasioned by

his feelings of guilt and

inadequacy after his short-lived marriage and the

increasing realization of his

own homosexuality. The fifth (1888) is also a

symphony about Fate, but here the

relationship is more comfortable, or at least

resigned. A decade after the

fourth, Tchaikovsky had probably come to terms with

his homosexuality, and

although he still felt guilt pangs, his acceptance

was accompanied by a

deepening religious conviction and renewed

confidence. A clear sense of this

self-assurance comes through in the symphony’s

triumphant finale.

None of

the late symphonies is

surrounded by more mystique than the sixth, however.

This is his last major

work, and it was written after a protracted

depression. The optimism of the

late 1880s collapsed when his longtime patroness and

confidante Nadejda von

Meck severed their relationship in 1890. Though he

was no longer financially

dependent on her, his correspondence with von Meck

had obviously been an

emotional support—she had been the one person to

whom he could open his heart,

even though they never spoke in person. Even

artistic success and international

fame was not enough. On a fabulously successful

American tour in 1891, he wrote

in his diary about feeling old and washed

out: “I feel that something within

me has gone to pieces.” By the beginning of 1893, he

had hit rock bottom,

writing to his nephew Vladimir Davidov on February 9

that: “What I need is to

believe in myself again, for my faith has been

greatly undermined. It seems to

me that my role is over.” But within two weeks, he

reported back excitedly to

the same nephew that he was composing “furiously.”

By August, when the Symphony No.6

was nearly complete, he

wrote again, calling it “the best, and certainly the

most open-hearted of my

works.” The supreme irony of this work is that, only

nine days after he

conducted its successful premiere in St. Petersburg,

Tchaikovsky was dead. The

old story about his death from cholera seems to be a

fabrication, covering up

what was almost certainly suicide. The precise

details of his death remain

a mystery, but one story that came to light in 1966

connects the death to a

romantic relationship between the composer and the

nephew of a Russian noble. Such

things were kept out of the public eye, but

Tchaikovsky was supposedly

convicted by a “court of honor” comprised of his

noble peers, and told to kill

himself to avoid embarrassment for all concerned.

Given the

biographical

circumstances of this symphony, Tchaikovsky’s

intended meaning is significant

in how we hear it. Its pessimistic tone, and

elements like the quotation of a

chant from the Orthodox service for the dead,

suggest that death was probably

on his mind. This is clearly a symphony with a

message—it was billed as A Program

Symphony at its first performance,

and in a letter to his nephew, he described it as:

“a work with a program, but

a program of a kind which remains an enigma to

all—let them guess it who can.”

Modeste Tchaikovsky, who composed a sort of

biographical program for the Symphony No.6

after his brother’s death,

maintained that the secret died with the composer.

However, some clue of his

intentions may lie in a brief note found among the

sketches for his Nutcracker

ballet, written a year

earlier:

“Following

is the plan for a symphony LIFE! First movement—all

impulse, confidence, thirst

for activity. Must be short (Finale death—result of

collapse). Second movement

love; third movement disappointment; fourth ends

with a dying away (also

short).”

It is

hard to escape the

conclusion that the Symphony No.6

is

autobiographical, the work of a deeply sad man. The

title was not Tchaikovsky’s

own: Pathétique,

not simply

“pathetic” as usually understood, but Patetichesky

in the original Russian implying poignancy and deep

sorrow. His brother Modeste

suggested the title the day after the premiere as a

replacement for the

composer’s own enigmatic Program

Symphony,

and Tchaikovsky appended it when he mailed the score

to his publisher

Jurgenson. The day after he mailed the score, he

wrote a second letter to

Jurgenson rejecting the title, but he was dead a

week later and the publisher

kept Modeste’s title, which has remained with the

work ever since.

What You’ll Hear

The symphony

is in four movements:

• A

large opening movement that

experiments with the conventional elements of the

form.

• A

lilting waltz...in 5/4!

• A

grand march.

• A

deeply sad and tragic

concluding movement.

In his

letters, Tchaikovsky

promised “much innovation of form” in the Symphony

No.6, and the opening movement certainly lives

up to this. Dispensing with

the usual conventions, he presents three related

ideas in three different

tempos: first a doleful bassoon melody, which gives

way to a faster version of

the same idea in the violas. A descending line at

the end of this section is

transformed into the lush third theme in the

strings. After an ascending answer

in the woodwinds, the theme enters again in fuller

form. The music dies

away—literally: never one for understatement,

Tchaikovsky writes the seemingly

impossible dynamic marking pppppp

(pianisisisisissimo!)

at the close of

the exposition. The development begins with a

crashing chord from the full

orchestra (merely ff — ffff

comes

later...). After a fierce fugato, the

bassoons and low brass solemnly intone a chant from

the Russian Orthodox mass

for the dead (“With your saints, O Christ, may the

soul of the departed rest in

peace”). There is no regular recapitulation, but

instead a continuation of the

furious motion of the development, following on the

heels of this chant. When

it reappears, the second theme is underlaid with a

nervous accompaniment

figure. The movement fades away with quiet woodwind

statements above descending

pizzicato notes from the strings.

Innovation

continues in the second

movement (Allegro

con grazia), a

waltz set in 5/4. This meter was almost unheard of

in orchestral music at the

time, and can often sound awkward and off-balanced.

Tchaikovsky’s melodies,

however, flow so naturally that this odd metrical

arrangement is scarcely

noticeable. The movement is cast as an alternation

between the gentle, lilting

“waltz” and a more pensive trio.

The third

movement (Allegro

molto vivace) is a march, but

this is not clear for quite a while. Quick triplet

figures are tossed off

between strings and woodwinds as tiny fragments of a

march theme gradually

emerge. When the march itself finally appears, some

70 bars into the movement,

it is quietly stated by the clarinets, and then

again by the strings. There is

a brief crescendo, but the dynamic backs off again

and the strings and

woodwinds introduce a countertheme. The march theme

begins again, still under

tight control, and there is a lengthy section where

tension builds to the

breaking point before the seemingly inevitable

statement by full orchestra. The

movement closes triumphantly with a descending line

in the brass and a triplet

flourish.

After the

noisy bombast of the

march, the tragic character of the finale (Adagio

lamentoso) comes as a complete surprise. The

main theme is given

immediately by the strings, and then again with

slightly augmented

orchestration, rounded off by a melancholy bassoon

solo. The second theme moves

to a somewhat brighter major key, and the mood

intensifies until an ominous

strike of the gong. The music builds to one more

peak before silenced again by

the gong and a dark trombone and tuba chorale. As if

exhausted, the movement

quickly dies away to nothingness.

________

program

notes ©2022 by J.

Michael Allsen