Madison Symphony

Orchestra Program Notes

September 23-24-25,

2022

97th Season /

Subscription Program 1

J. Michael Allsen

Our 95th season in

2020-21 was of course canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Much of that

season was to have been a celebration of the 250th

anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, featuring his music on

multiple programs. In 2021-22, we returned to Overture Hall,

with a season that nearly completed this delayed

celebration. However, this concert, initially rescheduled to

September 2021 was once again postponed due to continuing

COVID concerns. We finally complete our Beethoven

celebration with his Symphony

No.9, last and largest of his symphonies. The ninth,

ending with a great choral celebration of joy and humanity,

is the perfect work to symbolize coming through what we as a

community—and humanity as a whole—have endured since early

2020. Joining the Madison Symphony Orchestra and Chorus for

these programs are four fine vocal soloists: soprano Laquita

Mitchell, mezzo-soprano Kirsten Larson, tenor Jared

Esguerra, and bass Matt Boehler. The program opens with a

feature for our retired principal oboist Marc Fink, who

played in the Madison Symphony Orchestra for nearly half of

its 97 seasons—here we belatedly celebrate his retirement in

2020 after 48(!) seasons with the orchestra, with Mozart’s Oboe Concerto.

Mozart’s oboe concerto

is one of the genial instrumental works he composed while

working in his hometown of Salzburg. What the young Mozart

wanted most in the world at this time was a career as an opera

composer, and all three movements of this fine concerto have a

distinctly operatic sound.

Mozart’s oboe concerto

is one of the genial instrumental works he composed while

working in his hometown of Salzburg. What the young Mozart

wanted most in the world at this time was a career as an opera

composer, and all three movements of this fine concerto have a

distinctly operatic sound.

Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27,

1756, Salzburg, Austria.

Died: December 5,

1791, Vienna, Austria.

Concerto in C Major

for Oboe and Orchestra, K. 314

- Composed:

Spring or summer 1777.

- Premiere:

Probably in Salzburg in 1777, by oboist Giuseppe

Ferlendis or in Mannheim in early 1778 by Friedrich

Mann.

- Previous MSO

Performances: This is our first performance of the

concerto.

- Duration:

21:00.

Background

Mozart probably composed this

concerto for a Salzburg friend, Guiseppe Ferlendis.

In 1773, Mozart returned to

Salzburg after a childhood spent traveling the courts of

Europe as a Wunderkind,

under the supervision of his father, Leopold. He spent much of

the next eight years in his hometown, working as a church

musician for the Archbishop, Leopold’s patron. While the

younger Mozart’s main duties were connected with the

cathedral, he found time to compose a great deal of non-sacred

music—symphonies, concertos, and serenades—and to take a

leading role in the provincial but active musical life of

Salzburg. Many of the works Mozart composed in this period

were for friends and fellow musicians. One of these was

Giuseppe Ferlendis, the oboist in the Archbishop’s orchestra.

Ferlendis was just a year older than Mozart, and Leopold

described him as a “great favorite in the orchestra.” It is

not known if and when Ferlendis played the concerto in

Salzburg: Mozart left Salzburg in September 1777 on a

job-hunting tour to Mannheim and Paris, and Ferlendis left

Salzburg in 1778. We do know that Mozart took the score along

on this tour: he reported in one of his letters that oboist

Friedrich Mann played it at least five times in early 1778. He

also revised the work in Mannheim: when an amateur flutist

there commissioned Mozart to write two flute concertos, one of

the works he produced was a transposed and slightly revised

version of the oboe concerto.

What You’ll Hear

The concerto is in the traditional

Classical three-movement form:

• A broad opening movement focused on the development

of a few main ideas.

• A lyrical slow

movement.

• A fast-paced

closing movement alternating a main theme with contrasting

music.

The concerto is laid out in

three movements. The first (Allegro aperto)

begins with an orchestral introduction that lays out a pair of

thematic ideas that are distinctly operatic in character. The oboe enters with

the same themes, decorating them in the manner of an

18th-century opera singer. There is a short development and a

conventional recapitulation before a grand pause that allows

the soloist to play a solo cadenza. Mozart’s slow movements

are nearly always lovely and lyrical, and this one (Adagio non troppo) is

no exception: an aria for the soloist, often in gentle

conversation with the orchestra. Once again, there is space

for a short cadenza near the end. The final movement (Allegro) is a

good-humored rondo, in which a single theme reappears

throughout the movement in alternation with contrasting

episodes. The main theme is a rather military-sounding melody,

laid out at the beginning by the oboe. (Mozart liked this tune

well enough to re-use it a few years later as an aria in his

opera The Abduction

from the Seraglio.) In a somewhat unusual move, Mozart

leaves space for a third solo cadenza just before the final

statement of the main theme.

Beethoven’s ninth symphony is a profound

musical journey, from the mysterious, atmospheric opening,

through a massive scherzo, and a sublime slow movement. The

culmination is Beethoven’s enormous choral finale, setting

the ecstatic words of Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy. This

jubilant celebration of human dignity and freedom is as

relevant in 2022 as it was at the first performance in 1824.

Beethoven’s ninth symphony is a profound

musical journey, from the mysterious, atmospheric opening,

through a massive scherzo, and a sublime slow movement. The

culmination is Beethoven’s enormous choral finale, setting

the ecstatic words of Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy. This

jubilant celebration of human dignity and freedom is as

relevant in 2022 as it was at the first performance in 1824.

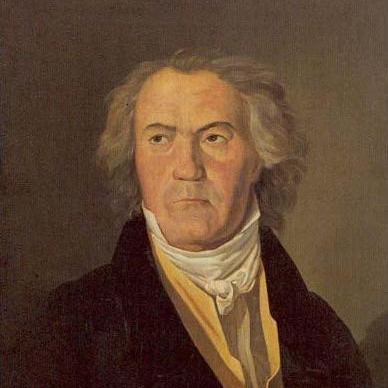

Ludwig

van Beethoven

Born: December 17,

1770 (baptism date), Bonn, Germany.

Died: March 26,

1827, Vienna, Austria.

Symphony

No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 (“Choral”)

- Composed:

Early sketches of the symphony date from 1815, though

the famous “Ode to Joy” melody is even earlier.

Beethoven began concentrated work on the symphony during

the summer of 1823, and completed it in February 1824.

- Premiere: May

7, 1824, Vienna.

- Previous MSO

Performances:

1935, 1976, 1980. 1995, 2004, and 2015.

- Duration:

65:00.

Background

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 was a

truly groundbreaking and radical work in its time, notable for

its complexity and unprecedented choral finale.

Almost a quarter of a century

separates Beethoven’s first and ninth symphonies, a quarter

century that saw encroaching and eventually total deafness,

personal tragedies, musical triumphs, and the composition of

Beethoven’s greatest music. There is also a twelve-year gap

between the completion of his eighth and ninth symphonies.

When we compare the Symphony

No.9 to the abstract works that Beethoven wrote at the

end of his life, it seems a bit dated. There are many

elements that seem to hearken back to the “heroic” style that

had occupied him in the opening decade of the 19th century.

Much more striking, however, are the new and innovative

elements: the extraordinary introduction to the opening

movement, the masterful contrapuntal writing, and of course

the massive finale—the first symphonic movement to include

vocal soloists and a chorus. This symphony had a profound

effect on virtually every 19th-century composer that followed

Beethoven, from Berlioz and Wagner to Brahms.

The symphony was not an

immediate success, and several reviewers wondered openly

whether Beethoven’s age and deafness might be beginning to

take their toll. Part of their reaction may have been the

result of a poor performance. The musicians hired for the Akademie concert on

May 7, 1824 had had only three rehearsals and it is obvious

that they did not have the new symphony under their fingers at

time of the premiere. (One eyewitness account, for example,

notes that the string basses had no idea how to play the

recitative section in the finale, and emitted nothing but a

confused rumble at this point.) Beethoven himself did little

to help the performance—he insisted on conducting, even though

he was completely deaf by this time. Even the most sympathetic

observers noted that his wild gestures were completely out of

sync with the orchestra. The performance was saved from utter

disaster by an assistant conductor, Ignaz Umlauf, and the

orchestra’s concertmaster. It was this concert that produced

one of most well-known Beethoven legends. At the close of the

finale, Beethoven was apparently unaware that the audience was

applauding until he was tapped on the shoulder by the

mezzo-soprano soloist, Caroline Unger.

We know a great deal about

Beethoven’s creative process—we have hundreds of pages of

musical sketches that document the evolution of his works. The

sketches, written in Beethoven’s nearly illegible handwriting

(He was writing for his own benefit after all, not for a bunch

of 21st-century musicologists!), show that the ninth symphony

had a long and complicated evolution. The earliest sketch

seems to have been a preliminary version of the scherzo theme

Beethoven wrote in the winter of 1815-16, and the musical

ideas that would be forged into the ninth symphony emerged

over the next few years. In his book about the ninth symphony,

Nicholas Cook explodes an enduring myth about this process,

that Beethoven planned not one, but two symphonies. The

essential plan of the ninth symphony—a four-movement work in D

Minor with a choral finale—seems to have been complete by

1818, but then Beethoven set the symphony aside for a few

years. He began serious work in the summer of 1823, completing

the Symphony No.9

in February of 1824.

Beethoven seems to have been

fascinated for many years with Schiller’s poem An die Freude (“To

Joy”—written in 1785). The poet and playwright Friedrich

Schiller was one of the leading voices of democratic thought

in Vienna, and his plays were occasionally banned during the

1790s because of their “dangerous” sentiments. Beethoven may

have thought about setting An die Freude as

early as 1796, and may in fact have composed a now-lost

setting of the poem in 1798 or 1799. Lines from An die Freude appear

even earlier, in a cantata Beethoven composed on the death of

Emperor Leopold II in 1790, and selections from the poem also

appear in his opera Fidelio

(1806). In setting An

die Freude in the ninth, Beethoven freely rearranged and

edited Schiller’s poem, focusing in particular on the lines

that deal with the winged goddess Joy, and the feelings of

brotherhood she inspires. The unforgettable melody used to set

Schiller’s poem had a similarly long history. Some scholars

have traced the “Joy” melody to as early in Beethoven’s career

as 1794, and it reached its nearly final form in his Choral Fantasy (1808)

and his song Kleine

Blumen, kleine Blätter (1810).

Beethoven seems to have been

fascinated for many years with Schiller’s poem An die Freude (“To

Joy”—written in 1785). The poet and playwright Friedrich

Schiller was one of the leading voices of democratic thought

in Vienna, and his plays were occasionally banned during the

1790s because of their “dangerous” sentiments. Beethoven may

have thought about setting An die Freude as

early as 1796, and may in fact have composed a now-lost

setting of the poem in 1798 or 1799. Lines from An die Freude appear

even earlier, in a cantata Beethoven composed on the death of

Emperor Leopold II in 1790, and selections from the poem also

appear in his opera Fidelio

(1806). In setting An

die Freude in the ninth, Beethoven freely rearranged and

edited Schiller’s poem, focusing in particular on the lines

that deal with the winged goddess Joy, and the feelings of

brotherhood she inspires. The unforgettable melody used to set

Schiller’s poem had a similarly long history. Some scholars

have traced the “Joy” melody to as early in Beethoven’s career

as 1794, and it reached its nearly final form in his Choral Fantasy (1808)

and his song Kleine

Blumen, kleine Blätter (1810).

What You’ll Hear

It is of course the great choral

finale, based upon Schiller’s text and Beethoven’s “Ode to

Joy” melody that gets all the attention, but the three opening

movements are just as revolutionary:

• A vast opening movement with a mysterious

introduction.

• An uncommonly complex scherzo movement.

• A serene slow movement that has complexities of its

own.

The opening movement (Allegro ma non troppo, un

poco maestoso) begins with a famous set of open fifths,

tonally ambiguous and suggesting nothing so much as boundless

space. Only gradually does it become apparent that this is in

fact in D minor, and the main theme is based upon the falling

fourths and fifths that spring from the opening sonority. The

movement as a whole is in sonata form—a virtual requirement

for symphonic first movements—but there is nothing typical

about the form here. He defies expectations throughout, going

to an unusual key for the second group of themes, and

upsetting the form by reinterpreting the main theme in D Major

in the recapitulation. At the end, after some 500 measures of

exhaustively working with his thematic material, Beethoven

introduces an entirely new theme, a dour figure that brings

the movement to a close.

The second movement, almost

invariably a slow movement in earlier symphonies, is here a

scherzo. Scherzos are typically lightweight and lighthearted

(or—in Beethoven’s case—blustery) movements, but the scherzo

of the ninth is expanded to match the proportions of the rest

of the symphony. The opening section (Molto vivace) is a

sonata-form movement unto itself: two groups of themes are

introduced and thoroughly developed, often in an intensely

contrapuntal manner. The trio (Presto) features a

complete change of character and meter. This section also has

elements of sonata form, developing a pastoral main theme. The

scherzo music makes an abbreviated return, and Beethoven ends

with his favorite musical joke: the trio’s music returns

briefly, making it sound as if it will return as well, before

he brusquely tosses it aside and ends the movement.

In this symphony, the slow

movement comes third (Adagio

molto e cantabile)—outwardly a simple and direct theme

and variations on a lovely hymnlike melody. However, he has

actually woven together two themes and two sets of variations

through the movement. The mood is almost universally sublime

until the closing section, when a strident fanfare seems to

hint at what is to come in the finale.

The enormous and complex

finale begins with crashing dissonance: Richard Wagner

referred to these measures as the “fanfare of terror.” The

passage that follows is something new in this symphony, and

has been imitated by many composers. In a rhetorical fashion,

he presents brief reminiscences of all of his main ideas from

the three preceding movements, linked by short recitatives

from the string basses and cellos. It is as if, like a

good public speaker, Beethoven is summing up all of his main

points before moving on to his peroration. He hints at the

“Joy” theme before presenting it in full in the low

strings—one of the most satisfying and profound moments in all

of music. The movement as a whole presents a series of

variations on this theme. After three variations, however the

“fanfare of terror” returns. Beethoven’s masterstroke, used to

introduce the voices, is a brief text of his own (“O friends,

not these tones…”) that he inserts before beginning An die Freude. In a

few short measures, this recitative changes the character of

the symphony—rejecting all of the storm and stress of the

previous music, and setting the finale onto a joyful course.

After the first set of choral variations, Beethoven inserts a

droll “Turkish March” that serves as the background to a tenor

solo, and gradually develops into an orchestral double fugue.

One more triumphant statement of the “Joy” theme, and then

another startling innovation: a thundering recitative for the

full chorus, doubled by trombones. There is an extended moment

of hushed awe that gives way to a second and even more

magnificent double fugue for chorus and orchestra. The coda is

full of irresistible joy: fast-paced orchestral passages

alternating with sublime vocal lines.

Interpreting the Ninth

In his book on Beethoven’s

string quartets, Joseph Kerman paints a picture of Beethoven

during the 1820s, an aging, deaf, and virtually unlovable man

“…battering at the communications barrier with every weapon of

his knowledge.” If this is true, what does the ninth symphony

mean? This is a

question that scarcely makes sense for most symphonies before

this one, but it is precisely this question that is

responsible for much of the huge collection of writing about

this work. The long transformation from the D minor of the

opening movement to the triumphant D Major of the finale seems

to beg the question, and interpretations are legion. Romantic

writers conjured up elaborate programs for the symphony. In

the political upheavals of the 1840s, the words of An die Freude were

sung as a revolutionary anthem...and today it is sung as the

anthem of the European Union. The ninth symphony becomes

immensely popular in times of war—during both world wars, each

side claimed the ninth symphony and Beethoven himself as

exclusive property. Richard Wagner saw the ninth symphony as a

forerunner of his own musical ideals, as Beethoven attempting

reaching beyond Classical style towards an integration of

vocal and instrumental music. Some music theorists have gone

to the other extreme, ignoring any interpretation of the text

to show the finale as a supreme example of Beethoven’s

development technique. In Japan, massive performances of the Symphony No.9 (often

including choirs numbering in the thousands) have long been a

New Year’s Eve tradition, and the symphony is accepted as a

symbol of Japanese cultural unity. Victorian English writers

found in the words of the finale an affirmation of Christian

faith, while during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s,

Chinese Communists interpreted the symphony as Beethoven’s

rejection of capitalism and his embrace of class struggle.

This is a piece with broad

enough shoulders enough to support a host of interpretations,

but in the end, it is bigger than any of them. It is not only

one of Beethoven’s final artistic statements, it is one of the

great works that define our culture.

________

program notes ©2022 by J. Michael Allsen